Photo credit: Caroline Davies

The Interview: Fiona Farrell

.

Fiona Farrell was born in 1947 in Oamaru and her upbringing there has featured in a number of her books, most notably in the 2011 novel Book, Book.

She is one of few New Zealand writers who have been nominated for the NZ Book Awards in all three categories—fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Her first novel, The Skinny Louie Book, won the New Zealand Book Award for fiction in 1993 and four of her later novels were shortlisted for those awards. The Villa at the Edge of the Empire was shortlisted in the general non-fiction category in 2016, and her collection of poems written in Ireland, The Pop-up Book of Invasions, was a poetry finalist in 2008.

Farrell has also won awards for her short fiction and for her playwriting, and held many prestigious fellowships and residencies both here and overseas. She received the Prime Minister’s Award for Fiction in 2007 and the ONZM for Services to Literature in the Queen’s Birthday Diamond Jubilee Honours list in 2012. Her 2018 public lecture, at the Auckland Writers Festival, on the political novel in New Zealand can be read in full here.

After many years living at Otanerito on Banks Peninsula, Fiona now lives with her husband in Dunedin. A new novel, The Deck, will be published in 2023.

This interview with Morrin Rout took place in November 2022.

You grew up in Oamaru in a home that valued books. Book Book gave us a real insight, albeit fictional, into the books that first intrigued and enticed you.

Yes, born and raised in North Otago. It was a lovely place to grow up: small, hilly, fantastic atmospheric old buildings — none of them specially cared for or labelled ‘heritage’ buildings. They were just there. The country round there was lovely too: lots of little winding white gravel roads, limestone outcrops, rivers and long sandy beaches where we could take our ponies swimming. Me and my sister and other kids just roamed about unsupervised. It was wonderfully free.

It was an interesting concept, using your life as inspiration for a novel. I’m not saying you were unusual in doing that, but I think it was the reason so many readers resonated with the book.

I’ve never written a memoir — I don’t know if I ever would. I’ve always felt a bit reluctant to write about my family. It would feel intrusive I think and I know I’d get things wrong and it wouldn’t be true or fair. Plus my sister would kill me. I changed things in Book Book — for instance, the funeral of the mother in that book is nothing like my mother’s funeral. My dad was a devout Catholic but my mother was an equally devout Presbyterian, very proud of her descent from Wee Frees who came out to Dunedin in the 1850s, helped build Knox Church and ran its Sunday School for years and years. So her funeral was at Knox, with ‘The Lord’s my shepherd’ (‘Crimond’) — very traditional, not like the funeral in the book where the mother makes a video and plays the piano for the hymns. That was someone else’s mother. I heard about her years later and thought it was funny. Book Book is based on my life but it’s fiction. I changed details and invented dialogue. But the books that Kate, the main character, reads – they are all 100% the books I’ve loved and been influenced by. They’re definitely ‘real’.

You often refer to the great opportunities offered by the welfare state, quoting the vast difference between the life of your great grandmother and yours. There’s a huge underlying sense of social justice or injustice in all your work.

I didn’t have a deprived childhood. Not at all. When I was small my dad had a job reading meters for the Power Board. My mum had given up nursing to stay home and care for us. There wasn’t a lot of money but we had a big garden so there was lots of soup, lots of bottled fruit. We didn’t own many books: I got Arthur Mee’s The Children’s Encyclopedia for Christmas one year — ten volumes in their own little wooden bookshelf. Amazing. I loved it, read it over and over, cover to cover. Hundreds of pages of British empire stuff, all those poems and tiny little black-and-white images of Great Art. And Enid Blyton, of course — hard core Famous Five, not wussy Secret Seven. But we borrowed heaps of books every Friday night from the public library so I never missed owning my own.

At mealtimes we sat round the table with our library books propped up against the teapot or the sugar bowl. It was how we avoided fights and arguments. My mum sat out in the kitchen with her feet (in Dad’s old socks) in the open door of the coal range oven, reading her religious books and pamphlets. My dad was injured at Alamein and got sick when I was about ten, a terrible painful arthritic paralysis that was a result of his war wounds. He’d sit up all night in bed, smoking and reading.

We weren’t deprived, but we weren’t well off either. We saved up for things like shoes or a winter coat. We didn’t get a car till I was ten, we lived in an old villa, and we voted Labour. Because of the first Labour Government —Michael Joseph Savage, Peter Fraser — my sister and I had been given this thing: ‘The Opportunity’. It was always said like that, as if it had capital letters. My dad had come out from Scotland in 1920 when he was eight, from the slums around the jute mills in Dundee. His dad had been killed in France only a few weeks before the end of the First World War, but his mum somehow managed to bring her children out here to New Zealand — six of them, the youngest only five. She didn’t know anyone here, and she had TB or emphysema from working in the mills. But she got them here, and survived another eight years, working as a cleaning lady in Oamaru to give them The Opportunity.

My mum’s family had had a farm at Merton, near Dunedin. Her younger brother, Rob, went to university and would have become a lawyer — the first in the family — but he got TB in his first year. It spread to his brain and he ended up in the hospital at Cherry Farm, a gentle shambling wreck of a man. My mum adored him. She had trained as a nurse and went up to Waipiata to care for him when he got sick. We used to visit Rob on Sunday afternoons. I hated going there, to Cherry Farm. The sunroom smelled of pee and the men were scary and unpredictable and it was all appallingly sad.

Neither Mum nor Dad got to go to the university. But there was absolutely no question that my sister and I would. And we would study arts, because that was what my dad would have studied if he’d had the chance: classics, literature, history. He said they were the only true education. There were studentships if you agreed to teach for three years on graduation. No student fees. No massive debt to repay. Fantastic. It still makes me mad seeing what was done to education in this country in the 90s. It should be free, funded by the state and staffed by professionals, all the way from early childhood to post-grad.

I suspect you were a clever girl at school. When did you first get the sense that you were or could be a writer?

I wasn’t particularly clever — good at English, that was about it. The local high school, Waitaki, had a great English teacher whose idea of teaching senior English was to have us read all of Jane Austen, which I think was pretty close to perfect. At primary school I had a teacher who let me read a chapter book I was writing to the other kids, week by week. It was an adventure story set on an island with a castle and I had no idea each week what was going to happen, but it was great to read it out.

At Waitaki I wrote poems for the school magazine, and an essay for a competition for North Otago schools commemorating Scott’s expedition to the South Pole. I think the news of his death had been telegraphed round the world from Oamaru or something like that — so they had this annual competition with a prizegiving and speeches in the Opera House. I wrote this total fabrication about My Visit to Antarctica, all very enthusiastic, when the idea of going to Antarctica, living in some container surrounded by snow and ice, actually made me feel nauseous. I still don’t think humans should be there. Just leave it pristine, to the animals who have evolved to survive without artificial assistance. But anyway, I won the competition for this total lie, which probably wasn’t the ideal encouragement.

It must have been a real lesson in the power of good writing and a testament to your skills of persuasion. I imagine it must have been a boost to your confidence when you went to university.

I went to Otago and did three years of English honours, a new course they were trialling with a small group studying English and American literature intensively, medieval to modern, with a little nod at the end to Janet Frame and a couple of New Zealand poets. I got married in my final year to another student who had a scholarship to Oxford to study medieval Icelandic literature. So we went there, and after three years, on to Toronto where I enrolled to do an MA then an M.Phil at the Drama Centre.

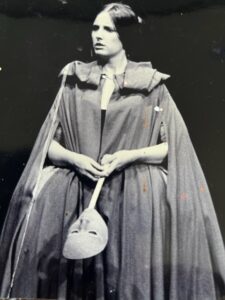

During the time (1971-76) spent in Toronto at the university’s drama centre. A rehearsal for a production of ‘The Way of the World’.

Theatre was your real passion then, wasn’t it?

Yes, that’s what I really loved at the time. I still wrote the occasional poem, but the main things I wrote were a couple of theses: one on a woman who was pretty much forgotten then, Aphra Behn, the first woman to make her living as a professional writer on Grub Street in London in the 17th century; and the other on a pencil manuscript for a poetic drama by T S Eliot. I loved doing the research — but the Drama Centre was also a highly practical place, with heaps of productions in the student theatre, lots of opportunities to act and direct. I really loved directing. Had we stayed on in Canada, that’s probably where I would have headed. But we didn’t stay. We had our first baby, and we wanted to come home. I wanted her to run around barefoot and go to big empty beaches and be fussed over by her grandparents and go to A&P shows and eat hotdogs on sticks with tomato sauce.

The set and cast of a play Fiona wrote and directed in Palmerston North in the 1980s called ‘Bonds’, in which three separate plays happened in three separate rooms. The set, built by Basil Poff, was complicated to construct.

Those years in Palmerston North with young children and busy jobs were a really productive writing time. I think you started off with getting a poem published and writing plays and then suddenly it seemed you had a book of poems, a collection of short stories and then your first novel, The Skinny Louie Book, the winner of the 1993 New Zealand Book Award for fiction, all published in a matter of a few years. And it wasn’t just getting published: you were winning prizes and awards in just about every competition, and for every genre that you were writing in – a pretty extraordinary achievement.

So yes, we came back. My husband had a job at Massey and I had another baby, and when she was about five months old, I got a part-time job at the local Teachers’ College, teaching a new course for students learning how to use drama in the classroom. I knew next to nothing about teaching, but I had lovely colleagues and the best part was that I found myself writing little plays. The students were supposed to do some practical work, and there simply weren’t any scripts available for groups of 20 (17 women and three men) and certainly not with a New Zealand setting or content. So I began writing them myself. Adaptations of myths, a musical about the Waihi Strike of 1912 based on a book one of my colleagues, [Yvonne] Stanley Roche had written based on documents and interviews with old people who remembered the events well. I was writing plays, too, for children in an after-school drama class I was running in town.

I’d stopped writing poems at Otago when I showed a boy who had had a poem in Landfall one of my sonnets. I thought it was rather good: it was about being misunderstood and it was based on a poem we’d been studying: Thomas Wyatt, ‘They flee from me that sometime did me seek’. The boy laughed, probably rightly. It was a bit pompous, but it meant I pretty much stopped writing poems. Just concentrated on the academic stuff.

Then fourteen years later when we were living in Palmy, my dad died and I wrote a poem, the way people do when they are really sad. I was fiddling with it one afternoon in the tiny office I shared with Stanley. She glanced over as she was scrambling round my desk to get to hers and read my poem. ‘That’s good,’ she said. ‘You should publish that.’

It’s weird isn’t it, how little it takes.

And it was published?

Yes it was, I think in the Listener, but maybe Landfall, and I then began writing more until I had enough for a collection, Cutting Out, which AUP accepted and published in 1987.

When did you start writing short stories – at the same time?

I was pretty busy — two children, a job, producing plays and so on — but I could manage to finish a short story. I sent one in to a competition in the Manawatu Evening Standard and it won. Then there were all these other competitions: there were a lot at that time and they were a big deal, with good prize money and overseas judges and award ceremonies and formal dinners. The BNZ Katherine Mansfield Short Story Award, the Mobil Dominion Short Story Award, the American Express Short Story Award. I kept writing stories and sending them off and I won them all and I know it sounds clichéd, but it was the most fantastic encouragement.

This was a time when women writers were starting to become visible, wasn’t it?

I’d been made redundant from my job at the Teachers’ College — all the part timers were laid off in a single cost-cutting sweep. Mostly women, trying to juggle jobs with family commitments. Only six women were left on the staff at Palmerston, and it was one of those ‘clicks’ that feminists were talking about at the time, when you realise that systems make things difficult for women. There were lots of clicks that year. Looking through Landfall, for example, for some poems to teach the students and noticing there wasn’t a single woman writer. Why not? Where were they? So writing the stories, writing female characters, seeing the stories published was a terrific buzz. It felt like a way that would cut through all this. I could write and be independent of any system. I could just write away on my own and no one could decide to make me redundant.

I understand it was Melvyn Bragg that supported your foray into novel writing?

I was writing short stories — they came out eventually in a collection, The Rock Garden, in 1989 — and entering these competitions and at one of the award ceremonies the judge, Melvyn Bragg, said to me, ‘Why are you wasting your time on short stories? You should try a novel.’ So I had a go. I took the story that had won that competition and another story, unpublished, set in the future when New Zealand is turning into a desert and people are battling over water, and I wrote my way from one story to the other. It became my first novel, The Skinny Louie Book, which won the fiction prize at the New Zealand Book Awards in 1993. That was how I began writing novels.

And then came your move to Christchurch. I wonder if you knew how significant that would be?

In 1992 I had moved down to Christchurch for a writer’s residency at the university. My husband and I were in the process of separating and at the end of that year, I met the man who became my second husband and moved with him out to a remote bay on Banks Peninsula.

How did living on the peninsula affect you and your writing? It’s such a stark, bold landscape – there are no soft green, rolling hills to ease the eye. The climate can be severe and you can be isolated for days at a time.

I lived at Otanerito for nearly 30 years. I never thought when I was younger that I’d live at the end of a gravel road: I’d always liked cities and towns with friends nearby and interesting buildings and lots going on — plays and concerts and people. But I loved living at Otanerito. I loved the peninsula. It’s a stunning landscape with all those deep indented bays and valleys. I loved walking over it, climbing up and down the hills, loved the weather: it did amazing weather. Great fogs that poured down over the hills, huge Antarctic swells that surged into the bay so the air thrummed, you could feel it in your bones, and amazing rainbows — circular ones and vertical ones and multiples. I loved the snow and being cut off for a few days — not too long, but three or four days of candles and quiet and cooking on the woodburner was lovely.

And though it was a long drive to Akaroa and Christchurch and seemed isolated, it wasn’t really. There were walkers every day from October to May. Around 54,000 stayed in our house in the time we were there and thousands more stopped in for a coffee or a swim at the beach, really interesting people. Plus friends visited and our family. And if I wanted to work, I had my hut up in the paddock. My husband set up my computer so it could receive a signal from down in the house and so long as the thistles in the orchard didn’t grow too thick, it worked really well.

I felt contained by the bay; I liked the rhythm of days there, and the shape of a year. I liked people coming down into the bay and being happy to be there. It felt good. I liked growing things, putting in fruit trees, and the writing was part of all that. I liked sitting at my desk and looking up from something I was working on, something I was imagining and seeing the bush up at Hinewai covering the valley all the way up to the skyline. I liked the sound of the sea, the rhythm of it, and the birds and the seals and that whole feeling of this beautiful world just ticking along. It was lovely.

We had to leave eventually. Age, energy, keeping the water running from a spring up the hill, a change in the way the track was routed that cut out the bay, all that. But for a long time it was really good.

The writing hut Fiona’s husband built in the paddock behind the old farm house they bought and renovated as trampers’ accommodation at Otanerito. ‘It was beautiful and looked straight up the valley toward Hinewai reserve.’

You’d used historical settings for your plays and several novels you wrote over that period could be categorised as historical fiction, Mr Allbones’ Ferrets (2007) and The Hopeful Traveller (2013) —or do you not count them as such?

Yes, I’ve written books that look like historical novels but they’re not really. I’m not really interested in trying to re-create the past. I don’t actually like historical fiction — I don’t believe it, for a start. It’s always fake, like those Pioneer Villages with bits and pieces piled into a room at random. I think all writing is contemporary. It’s completely bound up in the present. In the things we value right now.

So when I wrote Mr Allbones’ Ferrets it was because I was caught up in the debate around genetic engineering. I loathed the idea of fiddling with genes, and introducing these manipulated living forms into the world, specially here into this country, leader of the pack when it comes to species extinction. We were really aware of ferrets and stoats at Otanerito, trapping and so on, and watching the bird population recover.

I went up to Wellington and had a look at the papers of one of the men who had introduced ferrets to New Zealand back in the nineteenth century: a farmer, one of those arrogant knuckleheads who took no notice of warnings that it would be disastrous, just fixated on controlling the rabbits on his property. I came across his receipts for a shipment of assorted mustelids — ferrets, stoats, weasels. The agent who’d collected them and brought them out was called ‘Allbones’ which I thought was just such a great name for someone involved in helping trigger species extinction. I could have written non-fiction I suppose, but I don’t like coming at things head on. I like parables, and that’s what that novel is. It’s a parable that looks like a Victorian romantic novel. It’s even got a pink cover, a detail from a painting by Maryrose Crook that is exactly on the same wavelength. It’s a painting of a silk Victorian ball gown embroidered with images of all kinds of pests introduced into New Zealand, including ferrets. It’s called [The Sorrowful Eye of] The Pest Dress, and it’s absolutely beautiful, until you look closer and see what it is really about. It’s the perfect image for the cover of that book.

The Hopeful Traveller was a bit different. I was playing around with structure. I like doing that in a novel. I always think of books as objects. They are the perfect object to convey lots of complicated ideas and images in a compact form. When I’m beginning a novel, I start with the shape of it. I often have no idea what the book will be about, but I do know what shape I might play with: if it will be in lots of little bits — like the two quake books, all broken up, the way the city was post-quake and the way my head was dealing with reality at the time, all distracted and in pieces. Or maybe I’ll work with two related sections of six pieces each. With illustrations. That kind of thing.

Anyway, The Hopeful Traveller was about the idea of Utopia and it was written in two halves, both set on an island just off the coast with a little group of visitors, but separated by more than a century. So when the visitors come to the island it’s with different hopes. I wanted to write about this country — I always do. We’re living in such an experiment here, in a place where ideas of how people might live are being actively worked out. It’s a really exciting place to be writing. I remember thinking when I lived in the UK that it was lovely, with all that tradition and past and that long history of writers, but how much better it was to be here, working things out that hadn’t necessarily been written about before.

This country has been a massive experiment, right from the beginning probably — I don’t know, but I am guessing it has been like that since the very first waka came into shore. People coming from elsewhere who have to figure out how to live here, adapt, live alongside other people, determine where the boundaries will be, naming places and things. And since Europeans arrived, the experiment has become more complicated, and we’re still in the thick of it. Trying to figure out how we can live in this place.

I wanted to write about that and the idea of the ideal community. I’d been reading this French thinker, Fourier, who was a commercial traveller back in the nineteenth century and clearly had a lot of time on his own in hotels in strange towns in the evenings. He seems to have spent his time devising this fantastic, notion of the perfect community where everyone would have a place appropriate to their personality. So the serial murderers and psychopaths, the Neros, would be the butchers, using their natural tendencies to kill to supply the community with meat. (Fourier was a big meat-eater.) I just loved it — and that there were actually people (I read about some in America) who tried to put his ideas into practice. So that’s what The Hopeful Traveller is about — not history exactly, but a story told in two halves. You tip the book over to read each one, and you can decide to read the contemporary bit first, then go back to history, or the old bit first then up to the present. It was a kind of game I was playing.

During this period, you also had a number of overseas residencies, like the Katherine Mansfield fellowship in Menton, and the Rathcoola residency in Donoughmore, near Cork, in Ireland. The Pop-up Book of Invasions (2007) came out of the latter and it seems that the poems you wrote during your time there led you back home in many ways.

Yes — I’ve had a couple of residencies overseas. Incredibly lucky.

Menton was long established. I was the 26th writer to have it. I was there in 1995, an odd time in some ways — France resumed nuclear testing at Mururoa that year and there was a lot of protest, a second peace flotilla sailing from New Zealand. There were a couple of signs on walls in Menton but it all felt weirdly distant. We lived a kind of detached ex-pat life there — very pleasant, lots of swimming, nice walks, met some interesting people and I wrote the short stories that were published eventually as Light Readings (2001). The one set most strongly in the hills round Menton turned out as a kind of fairy tale, a bit detached from reality — and really that was how it felt being there: a bit detached, slightly unreal.

Donoughmore was different. It was a new residency for artists as well as writers. The resident before me was the sculptor, Denis O’Connor, the sculptor. I’ve got strong family links with Ireland through my father, but I knew very little about the place, so it was a real process of discovery for me, about Irish history which I found totally compelling, painful but compelling. And colonialism: how it was worked out in Ireland, then applied to New Zealand and what that meant in each place, if you were among the colonised on the one hand, and one of the colonisers on the other. I wrote really fluently there, just caught up in the place and all the ideas it prompted.

A reunion of Menton Fellows. Fiona with Vincent O’Sullivan at a writers’ session in le Jardin des Antipodes, owned and cultivated by New Zealander Alexandra Boyle.

But then the earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 shattered the tranquillity of life at Otanerito. Poetry seemed to come first in your response to the huge upheaval that the earthquakes wrought on your life and, from my memory of the time, that seemed to be the genre that most writers used to respond to their experiences in the beginning. The poems ‘The Horse’ and ‘The poem that is like a city’ were two of the most powerful and evocative for me. Why did you choose poetry or did it feel as though there was no other choice?

Lots of people reached for poetry after the quakes. Making things up when the whole city of Christchurch was in turmoil, in a mess beyond anything anyone had imagined, seemed a bit unnecessary. Poems are from the heart and direct and besides I think everyone was simply preoccupied with getting through each day, cleaning up, moving somewhere else if the house was totalled, dealing with insurers and so on. Novels take weeks, months, and a degree of calm.

You were personally affected by the earthquakes and your frustrations with and anger at the injustices being inflicted on people by EQC and the insurance companies drove the decision to write two books on this experience, one non-fiction and the other, a novel, Decline and Fall on Savage Street (2017). I remember sitting in a plane as I read the opening of The Villa at the Edge of the Empire in which you describe a map and I was able to look out the window and see the topographical features that you were referring to below me – I was aloft and detached with the god’s eye view you were depicting.

Well, I know I don’t have to tell you that the earthquakes were overwhelming! I mean, you’ve only just got your home repaired after what? Eleven years? They were utterly overwhelming and all consuming. I was completely caught up in the strangeness of them, the politics of the rebuilding, the way they exposed the reality of where I’d been living for twenty years. They also completely changed the way I knew people: suddenly people I’d known for years in one way, casually, as friends or colleagues or acquaintances were revealed as these extraordinarily brave and stoical and inventive human beings. Relationships simply shifted to a whole new level and they have never reverted from that. I don’t think they ever will.

I just fell in love with the people I knew and the city too. And all I wanted to do was write about it, try and examine what this place was where I had been living all that time with my eyes only half open. I loved meeting people through the interviews for The Quake Year (2012), and then I had this amazing piece of good fortune in being given a grant, the two-year Creative New Zealand Michael King Writer’s Fellowship to write a couple of books about the city. I wanted to write about it via facts but I also believe that fiction has a way of opening up reality too. I believe that feelings, which are at the core of fiction, are an equally valid — maybe more valid — way of understanding a major event.

I imagined the two books in a single box set, balancing one another. That’s never happened — but I’d like it to happen sometime and if I ever win Lotto I might see if I can publish them together like that. They took ages to write, of course, but it felt wonderful doing it. A total exploration.

Tell me about the joys and difficulties of collating Nouns, verbs, etc: Selected Poems (2020). I know a collection like this is a significant work in a poet’s career, a time of reflection. You say in the preface, ‘It’s so difficult in 2020 to convey just how it felt to be in this world where men, past and present, stood about booming to one another like so many kākāpo on a steep hillside’.

I wanted to say at the start of that book how very different it was when the first poems in that collection were being written, that odd world of domination by male writers, that has shifted so totally, especially among poets. Though at my granddaughter’s high school, a co-ed, I can’t help noticing she’s been taught only male writers. Still jolly old Baxter. None of the recent young New Zealand women writers, for instance. There seems to be a time lag at the universities where the teachers are being taught and that time lag and lack of research interest is affecting what’s being taught in schools. It’s hard to shift the monoliths.

I did love making a collected poems, gathering pieces together and seeing them come out in a handsome cover, with a ribbon. I’d always wanted a ribbon. I’m working on prose now — have been for the past two years, but that novel is almost due to be published and then I’m going to go back to poems for a while. I want to pay attention to the here and now and the fine detail, and poetry is the way to do that.

You take infinite delight in exploring language, the form, the use, the sound, the look, seemingly every possible permutation and combination. How we order and discipline it. There are those poems in The Inhabited Initial (1999) about punctuation marks, for instance.

I’m fascinated by the strangeness of words, the way human beings have developed this amazing capacity for nuance from a base of grunt and squeak. And then that further development when those words are translated onto a page or screen. It really is magical. And punctuation was part of that, the way signs are used to signal surprise or query or a pause for breath or whatever. The history of those signs fascinated me — that an exclamation mark for instance is actually a word — it’s a letter ‘I’ over little circular ‘o’ and it means Io, or ‘joy’, a Latin word that scribes inserted into texts when something wonderful and miraculous occurred. I’ve always loved that sort of thing. I was the sort of child who liked writing secret codes in lemon juice on bits of paper, or writing my name using the futhark [alphabet].

It seems like you have mastered every genre. Was it a progression from one to the other, or were you writing all simultaneously?

Sometimes I just like walking round a theme in different media — like an artist sketching something in pencil, then switching to oils. You get a different effect with each way of arranging words. I also like the feeling that I’m learning a craft, developing a variety of skills, that I know what I’m doing professionally. I know I hop about, from poems to short stories to plays to journalism and so on, but I think I would be bored if I kept working in just one genre.

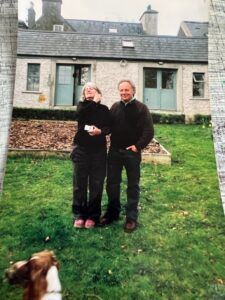

During a 2007 residency at Donoughmore in Ireland. Fiona and husband, Doug, standing in the orchard outside the gardener’s cottage that was their accommodation.

You wrote in The Broken Book (2011) about lying in bed as a child looking for faces and patterns in the paisley frieze in your bedroom. You said, ‘That’s what I do now when faced with the randomness of ordinary life: I insist that unrelated details arrange themselves in something I am capable of recognising … I try to write it down. Lines and circles forming in orderly rows across a blank white page.’

Writing for me is always exploring. I don’t plan. I simply sit down every morning and see what’s there. It’s a very peaceful meditative state. I’m constantly surprised by what my mind throws up. It’s a bit like dreaming really. I don’t usually recall what my dreams have been about, but those I do remember when I wake are always about a journey through unfamiliar territory. I’m usually on foot and I’m walking along tracks and roads through strange towns, in and out of unknown houses. It’s not an unpleasant sensation. I never plan when I start to write, nor do I consider an audience. In fact, it always feels like a bit of a shock when the book comes out and people begin reading it. I never anticipate that, for some reason.

Every time that I begin writing something I feel like a total novice. I have to learn how to do it all over again. I write very slowly, taking months, sometimes years to finish a novel. I love the feeling of sitting at my desk every morning, seeing if I can make the words work today, if I can solve the puzzle I’ve set myself. It’s incredibly enjoyable. It’s a kind of childish pleasure, really and I don’t ever want to lose it.

Morrin Rout has spent over 25 years organising literary events and festivals and producing and presenting book programmes on national and local radio. She is the former Director of the Hagley Writers Institute and is a current member of the WORD festival trust board.

‘Inspiration is the name for a privileged kind of listening’ - David Howard