‘I wrote partly because Landfall was there’

Writers on their first publications in New Zealand’s oldest literary journal.

Landfall, New Zealand’s longest-running literary journal, was founded in 1947. This week it publishes its 250th issue and a new name, Landfall Tauraka. Many New Zealand writers – from Janet Frame to Keri Hulme to Robert Sullivan – found a first home for their work in Landfall.

To celebrate its impact on our local literary scene and the way it has nurtured and showcased so many emerging writers, we asked some of our ANZL Fellows and Members about their first-ever Landfall publication.

C.K. Stead

Landfall, September 1954

Editor: Charles Brasch

Karl’s work has appeared more than 70 times in Landfall and – at almost 93 – he is now the second-oldest living contributor. The oldest is Owen Leeming, born in 1930 and a longtime resident of Paris.

I began writing poems and offering them to editors in my teenage years and by the age of twenty had had poems published in the Listener, the New Zealand Poetry Yearbook, and in Australia’s Jindyworobak Anthology. I offered poems to Landfall longhand before I owned a typewriter. Editor Charles Brasch was encouraging but didn’t accept any until 1953 when I was 20.

This was very exciting. Everyone who wrote seriously aspired to be in Landfall where all the notables of New Zealand lit of that time were to be seen. Brasch took three of my poems and they appeared in 1954: ‘Trapped Rabbit’, ‘Night Watch in the Tararuas’ and ‘Unexpected Meeting’. Slightly amended versions of the first two survived into my Collected Poems 1951-2006.

I’m re-reading them now, very much poems of their time and place, the first in rhyming couplets, the second in 7-line stanzas rhyming ababcdd. I had been very much influenced by our own poets – Baxter, Curnow, Glover, Fairburn – and I think the influence is probably obvious. They are solid, serious, solemn poems, tending like Baxter’s to moralise, with nothing of the wit that came later when I found, or made space, to be myself. I remember discussing ‘Night Watch’ with my mother and she was too discreet to ask who I had been to bed with. The answer would probably have been ‘No one. It’s all imagined.’

I had yet to learn, as everybody did, that the approval of Charles Brasch was not an infallible guarantor of quality. But Landfall (with the Listener too in those days, which still preferred text to pictures) was the public forum for the literary life – far more than it is or can be now, in this age of the internet and photography. I’m glad to have been there in what was its heyday. It deserves to be honoured as an essential part of our cultural history.

Trapped Rabbit

When the rabbit rattled the drag of a grasping trap,

Ran a few steps, crouched, laid back the flaps

Of ears against quivering fur, then seemed to play,

Lifting a twitching face that grinned and prayed;

When it tripped and ran to the tune of the wind-singing fence,

Stepping light-footed in exquisite, nervous dance

On the knife-edge knowledge of death; then heard our steps,

Its graceful frenzy bound in the weight of the trap

Collapsing clenched against steel and the waiting earth;

O when the hands made hard by the cycle of birth

And pain, closed on the warm-furred neck, and the bone

Clicked crisp in crystal air, the small stone

Of the head drooping towards earth as though

To burrow in shame from the living blue

Of a sky that could only smile: then I felt

No frame for guilt or superfluous pity, but smelt

The clutching clay at my heels, manuka breath

In the clear air, denying this shapeless death.

Witi Ihimaera

Witi Ihimaera

Landfall 95, September 1970

Editor: Robin Dudding

Getting published in the 1960s was all about paying your dues and earning it. If you aspired to write literary fiction you had to make your reputation in the academy: you couldn’t just roll up to the gate and expect them to let any old Tom, Dick or Hori in. So my sights were clearly on the New Zealand Herald, the Press, the NZ Listener and Landfall. And I was in a hurry.

In 1969 I decided to start my assault by publishing one story a month anywhere and when I hadn’t heard from Landfall about a story submission after a few months (I think it was ‘Porcelain Pig’: I had pretensions to write in the Frame mould), I took the opportunity of a flight from Wellington to Christchurch to go to see Albion Wright at Caxton Press and Robin Dudding, Landfall’s editor.

Robin’s son Adam writes in his book My Father’s Island that I pulled out a taiaha and performed a warrior’s challenge on the steps of Caxton Press. What I performed was a wero and I had with me the mere that I had been given by Pax and Maaka Te Ao Mamaaka Jones with whom I was staying. I wanted at least to scare the bugger.

I spoilt an otherwise beautiful sunny day. Robin was taken aback but waited patiently. And then he took me inside and calmed me down. He didn’t accept the story I had sent him though, but he was interested in my proposed first novel, Tangi. The next year, 1970 – you had to wait ages to be published by Landfall, which was a quarterly – a chapter from Tangi appeared called ‘Journey.’

In the ‘New Contributors’ list in that issue, Witi was described this way: Does not want to be only a ‘Maori writer’—he feels he has the advantage of living in two worlds, both of which he hopes he’ll be able to capture with words. His story was illustrated by Peter Gossage, whose art was also appearing in Landfall for the first time.

Opening of ‘Journey’

This is where it ends and begins. Here on the railway station, Gisborne, waiting for the train back to Wellington.

Here begins the first step into the future, the first step from the past. I am alone now. So long reliant on my father, so long my hand in his; now myself, my own keeper, for his hand has slipped away.

The platform is crowded with people. They stand in small groups, talking to one another. A well-dressed woman smooths her dress and pats at her hair. A young boy kisses his mother, then looks around, hoping nobody has seen. A little girl holds tightly to her father’s hand. A group of girls laugh and joke with a friend who is travelling from Gisborne this day. Rows of shiny cars line the barrier to the station. A green station-wagon pulls to a halt, and a son opens the back to get his father’s suitcase. Together they rush to the booking office, disappearing among the crowd […]

Soon I will board the train. I will sit at the window, looking out upon the platform. It will be crowded with people, shouting farewells. The train whistle will blow. The bell on the platform will ring. The train will move away, along the railway tracks as they cross the road leading into Gisborne from Waikanae. Red lights will flicker on and off at the crossing. The traffic will stop, letting the train pass. And I will journey away from Gisborne.

But I will leave my heart here, to be reclaimed when I return. This is where my heart belongs; this is where my life begins.

Fiona Kidman

Fiona Kidman

Landfall 96, December 1970

Editor: Robin Dudding

I had been knocking on Landfall’s door throughout the 1960s to no avail. I had had a number of short stories published in the little magazines of the time – Mate, Arena and even Te Ao Hou – but the drawbridge round Landfall was firmly pulled up. Why did I bother knocking? I was a housewife from the provinces, and Landfall was the precinct of clever men: Wedde, Sargeson, Baxter, Glover. Just often enough I would see the names of Fleur Adcock, Ruth Dallas or Anne Spivey, and, to the eternal credit of editor Charles Brasch, that of Janet Frame, to give me hope that one day I would make it. I am not sure, but I think Elizabeth Smither had a poem accepted by Brasch.

Don’t get me wrong, I admired the journal, and the scholarly and seemingly remote figure of Brasch, who at least sent courteous little notes of rejection: Not quite what we are looking for, but thank you for submitting. It all just seemed so inaccessible, so gentlemen’s club to me.

Then there was a sea change; after various upheavals at Caxton Press, and amid Brasch’s declining health, Robin Dudding was appointed the new editor. He was young, his personal life family centred, and he was seeking a fresh look at Landfall. He accepted my story ‘Flower Man’ about a group of young people who commit a dastardly deed on the last night of their school lives, effectively removing themselves from their country upbringing as they face their future in the cities beyond. I felt as if my true life as a writer had begun. Dudding accepted several stories and poems from me in the years that followed, as I gradually built up a repertoire that would find its way into books I wrote in the late 1970s.

That same year, 1970, I had moved to Wellington with my family. There were two surprising outcomes following the publication of ‘Flower Man’. In 1971, I enrolled as an English student at Victoria University. Professor Joan Stevens was overseeing enrolments and there was some delay while she queried whether it was appropriate for me to be enrolling when I had ‘already been published in Landfall.’ I don’t know whether she thought I already had a secret degree tucked away, or whether I would simply be a misfit among the 18- year-olds in the class. As it turned out, I was. An old School Certificate didn’t cut it with the smart young things I found myself among, and I slunk out six weeks later.

The other outcome was, a year after that, I was interviewed by the bookseller Roy Parsons and historian, Keith Sinclair for a job as the founding secretary/organiser of the (then) New Zealand Book Council. ‘Ah,’ said Sinclair, ‘that darling story ‘Flower Man’ in Landfall.’ His poem ‘Logic of God’ had been published in the same issue. Minus any other qualifications, I got the job and stayed in it for several years.

Fifty-five years later, I still get a special frisson if I’m published in Landfall. I don’t submit a lot of work these days, more poems than short stories, but acceptance means as much as it ever did.

Opening of ‘Flower Man’

The magnolia tree towered high about the church hall casting skeleton shadows in the winter, and providing deep green shade in the summer. In the late spring foliage, blooms could just be seen, heavy and exotic, the colour of whipped sour cream.

From where we lay in the coarse kikuyu grass at the end of the school playing fields, we could glimpse the tree. It was November, the air stripped clean ready for a Northland summer, and the sea not far away, sang promise.

There were four of us, Phyllis, Geoff, David and myself, who they call Magog, though my name is Marguerite. The nickname is apt though, for I have a peculiar mockery of a face, Grock-like, but it’s never been the hindrance it should have been.

.

Landfall 102, June 1972

Editor: Leo Bensemann

In the late 1960s I was living with my husband and young family in a remote area of Northland. We were teaching at a small two-teacher school there. I learned of a Penwomen’s Club, based in Auckland and decided to join as a Country Member. The Club held meetings, in Auckland, once a month which I was unable to attend. I hadn’t begun writing by then but was keen to try. The monthly writing competitions were just what I needed to get me started. I remember that I did quite well in these comps, especially in the category ‘Maori Story’. As far as I know I was the only Māori member of the club.

I came out the winner each year in this category, except for once when I was disqualified. Judge, Harry Dansey, gave full and positive comments about the story, but regretted that it was a late entry. The Club encouraged us to seek publication, and directed us to a manual, which listed the many magazines, journals and publications which would consider publishing our work. I had several stories published here and there, these eventually forming the bulk of stories of my first collection Waiariki (1975).

I know that I would have been thrilled to have ‘A Way of Talking’ accepted for publication in 1972 – such a long time ago. To have work published in such a prestigious journal was such a great endorsement for a beginning writer at a time when I was still wondering whether writing was going to be a lifetime endeavour.

Opening of ‘A Way of Talking’

Rose came back yesterday, we went down to the bus to meet her. She’s just the same as ever Rose. Talks all the time flat out and makes us laugh with her way of talking. On the way home we kept saying, ‘E Rohe you’re just the same as ever.’ It’s good having my sister back and knowing she hasn’t changed. Rose is the hard case one in the family, the kamakama one and the one with the brains.

Last night we stayed up talking till all hours even Dad and Nanny who usually go to bed after tea. Rose made us laugh telling about the people she knows, and taking off professor this and professor that from varsity. Nanny Mum and I had tears running down from laughing, e ta Rose we laughed all night.

At last Nanny got out of her chair and said, ‘Time for sleeping. The mouths steal the time of the eyes.’ That’s the lovely way she has of talking Nanny, when she speaks in English. So we went to bed and Rose and I kept our mouths going for another hour or so before falling asleep.

Elizabeth Smither

Landfall 109, March 1974

Editor: Leo Bensemann

Elizabeth is one of the most published writers in Landfall, second only to first editor Charles Brasch himself, with 79 poems and stories published over the past 50 years.

I can’t remember the subject of my first poem in Landfall – something short with a woman and goldfish? I think I was trying for something Japanese. Charles Brasch had phoned me and told me he had read a poem I had written pinned to the wall of a room in Maureen and Michael Hitchings’ home. Charles had a habit of walking about people’s houses and at dinner parties he could fall asleep while seated in the most elegant manner and then wake and reclaim his share of the conversation.

The poem on the wall was about Narcissus looking at himself in a pool. ‘You should be writing,’ Charles said, and when he hung up, I felt like dancing in the hallway. He didn’t take my poems at first – it took a couple of attempts – but I still remember the feeling of pride and happiness. It was really prestigious to be in Landfall, to know that your work had been examined by one of the exacting and scrupulous editors on the planet and that by some miracle you had passed.

The Goldfish

Her hair is still beautiful.

Now in the garden the mistress

Is trying to catch fish from the pond

The house he has bought her has

Red and black goldfish

Like good and evil: her hair

Is the colour of the red goldfish

She laughs and the water

Runs through the sieve

It’s hopeless: good and evil

Are so well-blended

She pats her own sleek hair.

Owen Marshall

Owen Marshall

Landfall 134, June 1980

Editor: Peter Smart

I began writing short fiction in the 1970s and New Zealand literary periodicals were important to me, not just as possible publishers of my own work, but as a means of keeping me aware of what my fellow writers were creating. My first stories were published in small magazines like Morepork and Pilgrim. I remain very appreciative of their support and also that of more enduring periodicals such as Islands and Sport. The Listener too regularly published short fiction in the 70s and 80s.

Chief among all such worthy supporters of our literature is Landfall, partly I suppose because of its tenacious survival over so many years, more importantly because of the standards it maintains. ‘The First Saturday in May’ was the first piece of mine that appeared in– and others followed. I’m grateful and add my congratulations to Landfall and its team on the 250th issue.

Opening of ‘The First Saturday in May’

We left the car back from the river, and nosed under the birches, so that when daylight came it wouldn’t be easily seen from the air. We pressed the doors closed instead of slamming them, and gathered at the boot to put on all our gear. The belts were heavy, and the shot in some of Henry’s cartridges rattled as he fumbled with the buckle. ‘My god it’s cold though,’ he said. The parkas were stiff because of it, and crackled as we put them on. The scent of the oiled japarra was similar to that of the guns we held. ‘A bit early to walk up I suppose?’ said Henry. Each year we had the same indecision. Each year we stood in the chill darkness and wondered when it would get light. ‘We could make a move do you think?’ said Henry. Eric leant on the car. He had both hands in his pockets, and his shotgun, broken at the breach, in the crook of his arm.

‘Remember what happened last year,’ he said, and he lifted one leg in its heavy wader to nudge the head of his dog. The year before we went too early, and after we put the ducks off they started coming back in the dark. We lost a good many because of it.

Fiona Farrell

Fiona Farrell

Landfall 144, December 1982

Editor: David Dowling

I was a late starter. My first poem was published when I was 35. I’d written poems and stories when I was a child, but in 1966, when I was 19, I showed one to a friend not much older than me, but he’d already had poems published in Landfall.

I’d never heard of Landfall before I came to Otago University. My family was more Oamaru Mail and Woman’s Weekly. But after a few months in Dunedin I knew it was important. Landfall was culture.

My friend laughed at my poem, and he was probably right. It was pompous, imitative of the Metaphysical poems I was studying. He had been reading the Americans. He knew a different kind of poetry was the future. So I stopped writing except for little scraps, gasps really, when life was just too big for prose. I kept them in a shoebox. Then in 1982 my father died, a difficult man, damaged by war, but loved, intensely loved. I wrote a poem to hang on to the chaos of feeling at his death, and another friend, a woman with whom I shared an office, glanced at it as I fiddled between classes one morning with full stops or commas. ‘That’s good,’ she said. ‘You should publish that.’

So I sent it to Landfall. And it did get published [under the name Fiona Poole], along with some other poems I’d written about the births of daughters and a son who didn’t make it.

When I was looking for that first poem for the Landfall exhibition at Otago University Library, I couldn’t remember the issue, but I did remember the cover: a sunlit veranda. Beautiful. Intensely female. Johanna Paul? Evelyn Page? I found it eventually and it was physical. Like finding a finger I’d somehow mislaid. I remembered how it had felt to see my words, not all smudgy from the Remington Portable, but typeset in a small space, a precious thing. My father with his damaged hands and cigarettes, his fishing sack and rages and frustrations and the warmth of his old gardening jersey was somehow being honoured here, his death noted among strangers.

That was the moment I knew I could write whatever I wanted and there were people out there who might listen. They’d nod and say. ‘OK. That’s interesting. Now, what else would you like to say?’

May ‘82

1

My father white as an onion dropped

heavy into earth hands

clamped to Christ.

Poppies dribble from old men.

They file towards the cannon on the hill

skirting the hole

this time.

2.

‘Cry for your kitten. Why

don’t you?’ he said. ‘Cry.’

But I dug my spoon in swallowed

every bit of cornflake furball swelling.

Tears—they’re easy.

For damp aunts and Bambi’s mother.

This pain is bulbous. It shoots

suddenly bud and branch.

Your throat hurts.

3.

The place is a mess and nothing

is where it used to be. Muddle and scatter.

And this fantail—poppybright

brisk as an angel—swings in the door.

For a minute death flirts in my kitchen.

On my cupboard. My curtains.

Death trills

that’s it

that’s it.

I crouch on an applebox cry for Dad

and an icecream from the shop

and a comic to make it better.

But the place is a mess and nothing

is where it used to be.

Anne Kennedy

Anne Kennedy

Landfall 156, December 1985

Acting Editor: Hugh Lauder

Having a short story in Landfall in the mid-80s, when I was a baby writer, meant more to me than I can say – on so many levels. But firstly, and vitally important, was reading Landfall. I wrote partly because Landfall was there.

Then, being asked to submit a story to the prestigious journal I fan-girled – and by guest editor Sophie Tomlinson, who although very young was already an extremely fine scholar – was a huge boost to my confidence. I remember I’d just gone through a period of being silent for a while (long story), and being in Landfall got me back in the game.

The story, ‘Light Document’, was, I remember, more experimental in style than I’d attempted before. I was excited to be allowed space to spread my wings, and that feeling influenced my development as a writer. I’ve never stopped experimenting.

Seeing a piece in print was a thrill. Remember in those days, it was just print. Landfall continues to be gorgeously tactile. Congratulations on the 250th issue, Landfall Tauraka! And thank you.

Opening of ‘Light Document’

My greatgrandfather the lighthouse keeper keeping sea memorabilia:

1. Shanties

2. Ships-in-bottles

3. Miracle fish from the IHS

4. Trove trunks of pearl paua gold

5. Miscellany of hove to, cove cave cape Hope beach light lore of old salts and saps and boys who’d run away to sea now beached—beached and found—up Cape Maria van Diemen falling between the seas.

……………………………………………….a n d

6. Tales from the sea

Tales-from-the-sea-and-the-sky from over the sea and from the pale Irish sky and the dark land. Under the new light the new blue and the yellow floral light there was one tale that became foremost called ‘Greatgrandfather the Light’ and it was of Greatgrandfather: keeper collector curator hunter and gatherer his stories scenes sea: the light archive.

There were other stories there was ‘The Queen Street Incident’ and ‘Mother Learns to Knit’ but it was Greatgrandfather who was the lighthousekeeper.

A lighthousekeeper is a lighthousekeeper Great grandfather was a lighthousekeeper.

Stephanie Johnson

Stephanie Johnson

Landfall 169 March 1989

Editors: Hugh Lauder, Mark Williams, Iain Sharp

When Landfall accepted ‘The Littlest Angel’ I was living in Sydney. I was a young writer, with a collection of short stories and a volume of verse to my name. The story is set in Waverley Cemetery, which sits above the cliffs of Bronte Beach.

Reading it again filled me with nostalgia and also the pride that I felt to be published in New Zealand’s pre-eminent lauded literary journal. The editorial board included Iain Sharp, a leading poet, for whom I have great respect. I felt accepted and acknowledged by my home country.

Opening of ‘The Littlest Angel’

For as long as I can remember I’ve stood about in a yard with many others just like me.

It’s a corner yard with a motorway on one side, and a hospital over the road.

On sunny days our white flesh glistens like quartz, and we sometimes afford a small smile at

a neighbour when nobody is looking.

Someone looking through the chicken wire from the road might notice.

That heavy-legged woman on her way to visit her husband in hospital.

We can see her looking at us and thinking which one?

The one with her hands clasped?

The one with wings?

The one without?

Usually we find it is a woman who chooses us. They live for so much longer.

Or perhaps a child might detect the slightest lift of a lip.

One of those quickeyed brown children with darting pointing fingers.

One of those slow vain children we are copied from, only we lack the blonde curls, the

peaches and cream.

That pink one with the panama hat. She could net an indiscretion in her bored gaze.

One of the workers might see us. There are three of them, not counting the one inside in the

suit.

The other three bend over us all day until we are finished.

Then we are placed out in the weather, shoulder to shoulder, very still, until the truck comes.

I have seen my sisters loaded into trucks, sometimes not without accident. A chipped nose,

the loss of a fold in a robe, a blunted curl.

The survivors stand in the back above the spinning wheel as the truck disappears down the

onramp to the motorway.

For miles the white of my sisters’ faces pierces the clouds of blue fumes.

Lord knows that they are thinking as they leave us.

Gregory O’Brien

Gregory O’Brien

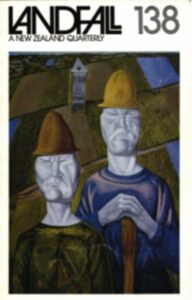

Landfall 138, June 1981

Editor: Peter Smart

Greg is another of Landfall’s most regular contributors: his work has been published in the journal 56 times.

As the 1970s came to a close, I was a solemn, 18-year-old, working as a journalist in Dargaville and spending long afternoons in my bedroom, listening to ECM records and reading James K. Baxter, D. H. Lawrence and recent issues of Landfall. The journal, around this time, had a strangely rural, not to mention ‘realist’, character. As an adopted son of Northland, I thought my poems would play well in that context, so I mailed three poems south, accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope.

Under the editorship of Peter Smart at the time, Landfall was going through a particularly catholic (with a small c) phase. It was fresh, lively and youthful – definitely uneven in quality, but somehow reflective of the broader life of the nation. Peter accepted my poems for publication in 1980 but, on account of his editorial largesse, there was to be a wait of just under a year as he cleared all the backed-up poems in his acceptance tray to make way for my momentous, monumental offerings.

Whatever the shortcomings of my three short, earnest poems, how great it was, in June 1981, to share a two-page spread with a writer named Dawn Seed. But it was the cover art of the first three Landfalls in which I appeared that made me feel I had ‘arrived’, albeit only by proxy. Following on the heels of the Leo Bensemann painting on Landfall 138, my next two appearances in the journal were in issues ‘covered’ by Bing Dawe and then Rita Angus. When my debut issue, Landfall 138, arrived in the post, I stared long and hard at Bensemann’s ugly, potato-headed orchardists in the painting on the cover and felt I was now happily one of them; I had a hand on the wheelbarrow that was New Zealand arts and letters. And from there I proceeded along my writerly path.

The Choice

Her cousin places

a jar on the lawn

to catch the rain that

falls from the still

leaves above the

lawns,

Her cousin never

reads books, he objects

to them on the grounds

that all the words have

been used before.

Landfall 161, March 1987

Editor: David Dowling, Linda Hardy and Hugh Lauder

Robert was recently appointed Poet Laureate of New Zealand, the first Māori poet to be awarded this role since Hone Tuwhare.

The first time I was published in a literary journal was in Landfall 161 with work accepted in 1986 by poetry editor Michele Leggott. I wrote about the oxidation ponds at Mangere in a long walking prose piece, my first environmental poem too, incorporating lines from Allen Curnow at the end for a dramatic flourish. One of the two other poems that Michele also accepted was the title poem for my first book, Jazz Waiata.

It was a buzz, to say the least, and firmed up my commitment as an 18-year-old to poetry. That year I also began editing the poetry page of the University of Auckland student newspaper, Craccum.

The next time I appeared was in Landfall 175 alongside Allen Curnow. Talk about walking on sunshine! Poems from my sequence in Jazz Waiata called ‘Tai Tokerau Poems’ were published there. The journal has continued to support my writing over the decades, and I’ll always be grateful for that. I am so happy to see Landfall continuing to flourish. Happy 250th!

Time Means Time in Tarawera City

for Allen Curnow

a helicopter took me over your spleen today, dove

straight through that rift, couldn’t land

on anger, ‘unprofessional’ pilots said floating

past graffiti: Turangawaewae Forbidden Antix.

late I trudged village track buried in pylons,

Manukau bridge flats, cymbaled roads in posts

counted tohunga’s hut surrounded by oversized

rubble—pictures tacked in a gallery; no green tane me

only mud pools and guts to nurse tired words, pricks

to wake old harm: a poet hurt monitoring the hot line

on a boomerang spin from lumpy water ae, at you!

I hate that wooden chest; I loathe village tours.

even let me hurl these grappling lines of phlegm

at your formica-mountain. Retch/cryscream/splay your ground!

nothing remakes nothing—apart from time.

I am nothing, say it. return the strands of earth.

'NZ literature is such a vast and varied thing' - Pip Adam