Image credit: Kelly Ana Morey

Conversation/Kōrero: #diasporatanga

David Geary and Alice Te Punga Somerville on the ‘Long-Distance Māori writer’

.

To celebrate the publication of Hiwa: Contemporary Māori Short Stories, David Geary – one of the anthology’s featured writers – and Alice Te Punga Somerville, winner of this year’s Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the Ockham NZ Book Awards, share their ‘free-flowing kōrero’.

Alice Te Punga Somerville (Te Āti Awa, Taranaki) is a scholar, poet and irredentist. Her first book Once Were Pacific: Māori Connections to Oceania (University of Minnesota Press, 2012) won Best First Book from the Native American & Indigenous Studies Association. Alice is a professor in the Department of English Language and Literatures and the Institute for Critical Indigenous Studies at the University of British Columbia. She studied at the University of Auckland, earned a PhD at Cornell University, is a Fulbright scholar and Marsden recipient and has held academic appointments in New Zealand, Canada, Hawai‘i and Australia. In 2023 she won New Zealand’s top award for poetry, the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry, for her collection Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised (AUP, 2022).

David Geary is a playwright, poet, fiction writer, dramaturg, director, screenwriter and kaiako. He is of Māori (Taranaki), Irish, Scottish and English blood. David lives and teaches in Vancouver, Canada, at Capilano University in the Indigenous Digital Filmmaking program and playwrighting for PTC Playwrights Theatre Centre. His short story “Hareruia (Saved Ya!) – a Taranoir” appears in HIWA: Contemporary Māori Short Stories and his latest theatre work: QEIII: Black Betty (a lost Shakespeare play) premiered in NZ in 2023 and has had readings at the 50th Banff Playwrights Lab and rEvolver Festival.

***********************

This conversation took place via email and Facebook messenger over August, 2023.

David Geary:

THE SHORT ANSWER THAT’S NOT VERY SHORT

I’ve always felt like a long-distance Māori so my writing has in part been about trying to close the gap. With my short fiction I’m challenging myself to write things that will bridge the gaps in my knowledge and in my connections to all things Māori. For example, I’ve always been fascinated by Titokowaru (Ngāti Ruanui and Ngāruahine) so my story ‘Hareruia’ in Hiwa features a man, Tito, who is named after him. I grew up fascinated by freezing works culture, so I mashed Tito up with one of my Dad’s Feilding works stories and moved it to Pātea.

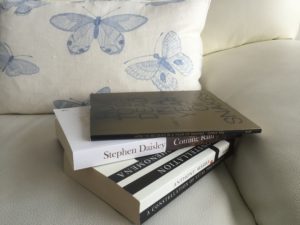

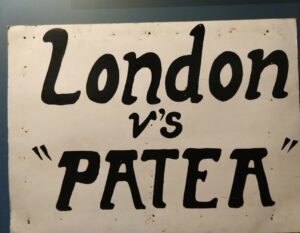

This is a photo I took of a 1982 protest sign when the London owners of the Pātea Works decided it was easier to close it than do an upgrade. I snapped it on a July 2023 whistle stop tour to the Museum of South Taranaki.

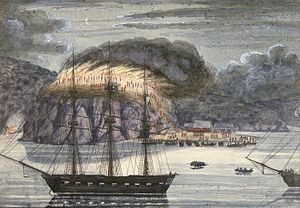

Above is detail from a drawing by Walter Jefferson Leslie at the trial of Te Whiti [Wellington]. The Evening Press 1886. Ref: B-034-015 Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Titokowaru (left) Te Whiti (right). I had this on the wall while I was writing ‘Hareruia’. I surround myself with such talisman / #moodboards then do commando-artist-researcher raids whenever I get back home. Is Aotearoa home? I have a lot of emotional geography with Canada now. I call it home too. I love the Stephen Stills song: ‘Love The One You’re With’.

.

THE LONG ANSWER

The long answer is very long. It’s the start to a creative non-fiction magical realism novel.

The Long Answer starts with Mum telling us kids we had Māori blood. That my Irish-English great-great grandfather, William Geary, was convicted in an 1834 Nottingham court of stealing two bushels of wheat and sentenced to seven years transportation (prison and hard labour) in Tasmania. When he was released, he became a whaler on the Otago peninsula, did okay, went on a trading trip up north and bought a Māori bride for a sack of spuds. We didn’t know her name or where she came from until my mid-30s.

In between there were two large family reunions, pilgrimages to Taranaki, a magical mystery tour, moments of great coincidence/guiding hands, and a tokotoko kōrero. See below:

This taonga belonged to Etahi Taputai (one of the names we finally found for my Māori great-great grandmother). It had been passed down through generations and hidden up a chimney. The long story also holds the horror of finding the only photo of Etahi had been lost/burnt, but the names on the back were remembered: Taranaki, Te Atiawa, Nga Mahanga, Porikapa. There is a story that Etahi was given this tokotoko when she left her people and moved South to be with William Geary. It was her connection to where she came from and had healing powers so was put in the beds of sick children. I take some comfort that she was a ‘long-distance Māori’ long before me.

In the same way, when you think about it, there is a great tradition of Polynesians being long-distance storytellers. We canoed from island to island, and within islands, for centuries, and continue to do so, so we were often a long way from our ‘homelands’ and facing the prospect of never going back, so creating/telling stories was part of taking those islands and peoples with us to new lands.

Where am I now? Well, I was back in Aotearoa for most of July 2023 and went to the hui in Palmy of all eight Taranaki provincial iwi to discuss the ratification of the deed for Te Mounga’s return to iwi control. I hongied Jamie Tuuta and the other movers and shakers. I asked probing questions about why we couldn’t get what Tūhoe got in the Urewera, and I reported back to our 500+ Etahi Taputai Geary Whanau Facebook group (I’m an Admin) on the event.

I also took long lost cousins to our Ōakura and Puniho Pā, stayed a night, met up with the locals we’ve built connections to, and bought the tino pai newly published Nga Hekenga o Ratou Ma – The People’s Journey pukapuka by Keith Manukonga & Carol Koha. See pic of happy cousins with Keith (left) in the Puniho kitchen.

But I’ve never lived there. In fact, growing up in the village of Rangiwahia in the Manawatū high country, the Ruahine Ranges were my mountains and Taranaki was a foreign country that contained our enemies on the rugby field. In short, I still feel distant, will probably always feel distant, and feel keenly my Māori identity has been constructed long after the fact.

I’m mostly okay with that. Living in Canada for 17 of the last 20 years, I see how great a job colonialism has done around the world to separate Indigenous Peoples from their identities and a lot of people are in the same waka as me – Searchers.

I’ve also been lucky/guided to find Māori and Indigenous in foreign parts (#diasporatanga – Kia ora, Alice!) who’ve helped me get closer to ‘the real thing’ whatever that might be. In 2003, we moved to Victoria, BC, Canada, and I left behind in New Zealand a project that included the Ngāti Whātua Bastion Point occupation. I figured I’d have to leave the project until I was in the Velox rugby club and someone pointed me towards a most welcoming Māori guy – Alec Hawke, who lived in Victoria. He was part of the famous Hawke whānau at the centre of the Bastion Pt occupation. He invited me to his house for regular guitar singalongs with another Māori transplant, Beau, who’d been in the NZ navy with Buck Shelford. They taught me all the old school waiata that I still use to support my pepeha. They taught me the haka. They took me in.

Similarly, when we moved to Vancouver in 2010, I went to a Waitangi Day celebration and met Wayne Te Kanawa, who invited me to the Te Tini a Māui kapahaka group. I learnt more but also that I get heel spurs if I stamp the ground too hard. Truth is they were professionals and far too flash for me but they did help me get over myself. They re-ignited my hunger to do more and learn more, so when Charles Koroneho (an old Wellington mate of a mate) came through town I did his rākau workshop. When Louise Potiki Bryant of Atamira Dance Company came, I did her dance workshop. When Hana O’Regan came to UBC to talk te reo revitalisation, I was there. I was hungry. And when Witi Ihimaera came to the Vancouver Writers Festival after commissioning me to write some modern Māori myths for Pūrākau: Māori Myths Retold by Māori Writers, I was there.

Old theatre mate Rena Owen was in town shooting an American mermaid show so I took her along (Yes, as Nick Cave once quipped: ‘David, you’re a terrible ****ing name dropper’). I’d never met Witi, though we’d once emailed about how I kept putting Māori as outsiders in my early plays (for obvious reasons, ie: I felt like one myself).

I loved that Witi had called my stories ‘subversive’. We chatted and I told him a (shorter) version of this story, about how I’d started out as a kid saying I’m ‘part-Māori’ and, as a maths nerd, was obsessed by my fraction of Indigenous blood: 3/32s (Another longish story – my Geary grandparents were related: half-aunt half nephew half cousins #totalscandal). ‘Oh, you’re one of those Māori,’ teased Witi.

Yes, ae, I am. I’m what I call an Outside-In. I’ll always be jealous of those who grew up knowing their whakapapa and their tūrangawaewae and where the macrons go. Jealous of those who are fluent in te reo, those who never feel like they’re on shaking ground when they represent, and/or fear that someday they’ll get called out as a fraud – a plastic tiki Māori.

This shakey feeling seems even more pronounced now in Canada and the USA where Pretendians are being outed. Check out the great doco on this by Ojibway playwright Drew Hayden Taylor (@TheDHTaylor).

The issue of distance has been huge in this debate as people claim Indigenous ancestry but have never visited their homeland or built any connection to it or its people. Joseph Boyden the novelist and Michelle Latimer the filmmaker have been two high-profile cases, and there’s been many accusations and examples in academia. However, I like what my friend Lisa Cooke Ravensbergen (Ojibwe/Swampy Cree/Irish/English) says about how we shouldn’t be calling people out so publicly but calling people into community to discuss these issues. That said, I also see the anger that arises when individuals claim funding and privileges based on an identity that is, well, distant.

Are there advantages to being distant? You bet. I get to learn and teach about the Indian Act and Truth and Reconciliation in Canada while comparing and contrasting what I know (and keep learning) about the Te Tiriti o Waitangi and ongoing colonial projects in Aotearoa. I’ve now spent more time in circle and conversation with Indigenous elders of the Coast Salish peoples than back home. I’ve been blessed to experience manaakitanga with Chief Ernie George (Tsleil-Waututh), Elder Latash Maurice Nahanee (Squamish, Hawaiian), David Kirk (Stó:lō), and so many others who’ve shown me aroha when they saw the loneliness of the long distance Māori.

This generosity also extended to my writing in Turtle Island (though not all Indigenous here take the turtle as their creation story). My story #WATCHLIST in Black Marks on The White Page (reviewed by Paula Morris) features The Wild Woman of the Woods that Beau Dick (Kwakwaka’wakw artist, activist, master carver, and Chief) shared stories of. I’d never have known that world unless I was away. Similarly, my story ‘Jumpers On Both Bridges’ in Bawaajigan: Stories of Power about a First Nations pizza delivery boy, trapped in a colonial traffic jam with the Ghost of McGyver, could never have been written if I hadn’t travelled, explored, made new connections, gone away.

So being away has given me some new perspectives, new material, and for all I lose by not being on the ground in Aotearoa, I gain other things by having some distance. You also get to experience what others perceive Māori to be.

Funny story: I was at the launch of Bawaajigan signing copies when an Indigenous guy asked me what I was doing.

‘Oh, I have a story in here.’

‘Which one?’

‘This one.’

‘Oh, you’re the Māori guy!’

‘Yup.’

‘Can you do a haka?’

‘…Yes. Yes, I can, but I’m not going to do one right now.’

‘Do you have any tattoos?’

‘No. No, I don’t. Because I also descend from Irish convict stock and they never got tattoos because that’s how the cops trace you.’

That left him suitably flummoxed and I got away. It reminded me how we often have to perform our identities, especially those of us who can pass as white folks with tans. And how desperate I have been to perform mine at times because I’ve felt so distant.

This has got quite long. And I haven’t even talked about the internet and Zoom bringing us closer, and all the brilliant books (like Alice TPS’s) that take us inside, and the movies and podcasts, and the socials (Alice and I wrote a lot of this via Facebook Messenger). And how being away you can connect with a bunch of awesome Indigenous writers, artists, academics, communities. I also haven’t mentioned that in my family I am ‘The One Who Went Away’. Right from 13 when I went to boarding school, I was the one who went away, and has basically just kept going further. But that’s enough about me. Over to you, Alice…

Alice Te Punga Somerville:

Wow e te whanaunga what a place to say ‘tag – you’re it!’ My mind is full of all the connections we share and all the ways our journeys have criss-crossed and diverged. Of course, our main and ultimate point of connection is Taranaki. I love that you got to go to an in-person hui about the ratification process around the maunga; what you have shared about connecting and asking questions and sharing the information with wider whānau maps on to my experience of the process too. I received nudges from my always-on-the-ball Mum of course, but also from my cherished Taranaki iwi cousin Rachel Buchanan who has made her adult and family life in Melbourne – and whose sharp thinking I always enjoy about home and away and also about how Taranakitanga (more specifically than what we might sometimes still call Māoritanga) provides a context for thinking about Indigenous mobility, refusals to fit within conventional boxes, and so on.

Rachel included me on an email blast about becoming informed about the kaupapa of the maunga. Then, a couple of Saturday nights ago I joined a zoom session at 11pm that they were running for the diaspora. I must admit, I remember when 11pm on Saturday nights was the time to refresh the lippy and head out to whatever Aotearoa city I was living in rather than the time to open the laptop while wearing PJs and join a two hour zoom informational session (with headphones so it didn’t wake my five-year-old daughter) while living on Musqueam whenua – but life moves on and here we are. I was so excited when I saw the special zoom session for the diaspora listed in the email blasts about the ratification; the 11pm timeslot was far less practical for me than other listed sessions but I wanted to make sure I turned up to that one so they didn’t think: ah well, there aren’t many people in the diaspora who care anyway.

#DiasporicDocumentation Eagerly tuning into the Taranaki maunga zoom session late on a Saturday night – door open and fan on because it was a hot summer evening. (Just out of shot: v necessary cup of coffee.)

My own connections to Taranaki are via the Wellington end of ngā heke – I grew up knowing that we were from Waiwhetū specifically and the Wellington area more broadly. Wellington: where I was born, where the grandparents were and I was sent for school holidays, where I chose to move and start my academic career. I always understood that these Wellington affiliations could be traced to Taranaki but the last person to live there (until my sister Megan, who has actually moved to Taranaki in the past month) was my great-grandfather Hamuera who, despite being born at Waiwhetū in the Te Ātiawa community there, was raised with his sister by his Taranaki iwi grandmother after their parents’ marriage busted up. So. I guess for me this naturalises the idea of mobility and migration not just as pushing the ejector button on your seat and rocketing off into outer space to drift around forever – but also as a dynamic process of shuttling between places, maintaining connections and commitments with both (or all), affirming the significance of relationships at both (or all) ends, and hopefully finding ways to contribute to both from the strength of knowing the other place too. I mean this is the diaspora dream, right?

Kupu/ Maunga/ Kupu

In the beginning was the maunga

And his descendants, like an upturned bucket of tiny stones,

Spilled along ridges and gullies and tumbled from those to the ends of the earth

The difference between speaking from speaking for and speaking to Taranaki

Is sometimes potato potahto

And sometimes chalk and cheese

For the smallest stones that have rolled the furthest

The most the best the only thing we can do

Is quietly join kupu with kupu like lego bricks, hoping they build something for someone

Someone asked a far-flung pebble to connect someone else with Taranaki writers

Before the second someone replied oh that’s okay I prefer to work with whoever the elders say

And what can a distant pebble do but nothing

Paperwork and documents and land block shares

Are loaded with kupu that can connect

Even as we wish they had fallen from someone’s mouth instead of a page

So many moving tiny stones – are these the destruction or extension of a maunga?

Kupu carried to and from Taranaki in mouths on maps in poetry on paper

An unexpected form of mortar cement clay

Whakawaiwai ai te tu a Taranaki

[The last line of that poem references the first line of a nineteenth century composition by Mere Ngamai (Te Ātiawa) who, as I understand it, was unable to return to Taranaki for a tangi so wrote a beautiful mournful waiata about proximity and distance.]

I first left home in August 2000. I didn’t mean to leave Aotearoa for longer than the five years it would take for me to get a PhD from a university in upstate New York. Several months earlier in the Fulbright NZ interview room I stood explaining why I wanted to study in the US, holding up an unfinished flax kete and proclaiming with confidence that my intention was to learn how to finish weaving its sides in the context of unique opportunities offered by academic life overseas but then, after weaving and filling the kete, I would bring it home.

A few years later, at the end of the brief required third-person ‘biographical sketch’ at the beginning of my dissertation (what they call a thesis in North America), I wrote: ‘She has now spent enough time looking around the world, and plans to spend the rest of her life in Aotearoa, working on her Maori language, raising some babies, reading + writing + teaching, and never stopping her habit of singing badly to the radio whilst dancing around her kitchen cooking yummy food.’

Yes, that was the dream of myself when I was about to enter my 30s. I had, as my Grandad had done with the 28th, seen the world and was going to stay home forever. My dream was so wide-eyed that reading it now, close to two decades later, I feel aroha for that hopeful young wahine who had no idea of what was to come. It was a good dream, but – primarily due to my inability to withstand the pressures of structural racism in NZ’s university system (twice) – it’s not how things turned out.

Since moving home in 2005 ‘to spend the rest of [my] life in Aotearoa’ (LOL), I have walked through the departure gates at Auckland airport to embark on a new life beyond Aotearoa three more times (to Toronto for a sabbatical in 2011, to Honolulu for a job at the University of Hawai’i in 2012, to Vancouver in February 2022): each time I have held a different ratio of grief/ despair and anticipation/ hope in my carry-on luggage. (I am yet to learn how to travel light!)

Last goodbye through the glass with my beloved nephew Matiu (who was born in March 2005 shortly after I arrived home from Cornell) in the Wellington departure lounge, August 2012, bound for Auckland then Honolulu.

DG: Arohamai, I’m going to interrupt and say: Ditto, Cuz, to the inability to travel light. I once walked up to the check-in counter of Air NZ trying desperately to not be lopsided, lifted my bag up onto the scales, and the handle broke off! #booksarebricks

ATPS: Books are bricks – and when we moved here last year I had 45 boxes of them! (But when you’re a scholar of Indigenous writing, you know that so much will be out of print in five minutes, it’s hard to source texts published in other countries/ empires, and libraries aren’t guaranteed to have a copy.) I have no current plans to go home with a one-way ticket. So, I can tell a story of writing in exile. I can write about writing while ‘not there.’ I can write – and I do write – about the shreds of grief, anger and betrayal that still coil around the supple unbreakable threads (aho? taukaea? tāngaengae?) that connect me to Aotearoa. I can write about the process of healing over the past year and a half that has included the challenge and opportunity to reconsider long-held (and already twice-attempted) dreams of an eventual return to teach at a NZ university – maybe the kete I held up at the Fulbright interview is endlessly unfinished, and continuously spent/ replenished, and that’s okay too.

One

Bridges I long assumed were the only way to cross,

that connected here to there, have washed away.

Structures I thought I depended on so deeply

that I scraped knuckles and bruised knees in efforts to patch them during storms;

Expanses of metal and concrete that plunged into depths

and stretched confidently from one bank to the other: gone.

I spent so long walking alongside this river, looking back.

I spent so long walking alongside this river, looking back.

Today, for the first time, no bridges were in sight anymore

no matter which direction I looked: none further inland, none nearer the sea.

Something else has changed:

the river itself has stopped looking like a threat.

As I paddle into shallow water, clinging long strands to keep balance,

I find the outgoing tide has left a long flat path of sand.

Why did I spend so long trying to walk in the air?

They say that only fools build houses on sand

but maybe some of us find safety in tides instead of walls.

But, writing not-there is only ever one way of being a ‘long-distance’ Māori writer, eh. For me, I have at least three more ways to spin the story.

DG: Okay, spin away. Three More Ways To Spin It Other Than not-there:

ATPS: First, as you have already shared above, David, neither of us is living in a place called not-there – we’re both also here. Living somewhere with eyes and heart only ever fixed on a previous home, and with little interest in or connection to where your feet are currently standing, is colonialism. Sure, colonialism is easy to spot in those ridiculous Māori-bashing rednecks who are scared of co-governance (DG: ‘Co-governance is never mentioned in the maunga ratification deed but that’s what’s happening’ – Jamie Tuuta) but can be less overt or palpable (perhaps deceptively/ dangerously so) when we ourselves participate in invisibilising other Indigenous peoples in places we are living. There’s no point carrying on piously about tangatawhenuatanga if you don’t also think about, and know how to practice, manuhiritanga.

For me, I have lived, worked and written in Ithaca (on Cayuga Nation/ Haudenosaunee territory,) Toronto (on Haudenosaunee, Mississauga and Anishinabe territory), Honolulu (on Kanaka Maoli ‘aina), Sydney (on Dharug Country), Hamilton/ Kirikiriroa (on Waikato Tainui whenua) and – since February last year – Vancouver (on Musqueam territory). I am deeply shaped by these places and by the people of these places; my own journey with writing cannot be extricated from the teaching, experiences and aroha (yes, including aroha in the form of tellings off!) I have experienced in each of them.

As a writer, I have been in community with Indigenous writers in these places, but I have also learned from their respective contexts about local configurations, frameworks, networks, stakes, tensions, risks and triumphs of Indigenous writing. I’ve been nudged and challenged and stretched in all the best ways but also in ways that can be humbling, disorienting, awkward and sometimes just plain old embarrassing. Spending time on other whenua provides the chance to rethink Aotearoa too: understandably, we can be stuck in some really New Zealand-shaped and British-Empire-shaped ruts in our thinking; aspects of our experience that feel intractable, inevitable or unimaginable can suddenly seem quite different when in conversation with Indigenous people elsewhere.

I hope I have also taken opportunities to contribute what small things I can to those local contexts – the line between engagement and appropriation/extraction can be perilously thin! I also hasten to add that it’s cool that I experience these places as Indigenous places but the ease of my movement into them is made possible on a pragmatic level by my New Zealand passport that is both the symbol of our oppression by a violent colonial state (how can a rich state that is happy to let us die earlier than everyone else be understood as anything but violent) and my ticket to ride.

Written yesterday

It’s Valentine’s Day at this far edge of the Pacific

Clouds hang heavy, obscuring the shape of the land

Cook never made it here

But, according to Wikipedia, he made all of this possible

I now live in the most livable city in the world

Named after a man who, they say, died in obscurity

One Of Those White Men whose names are all most of us know

about places they barely touched

Vancouver

Vancouver

Vancouver

Whose names have become lines we are forced to repeat to repent of our sins

Vancouver who was born in Norfolk

(Pauline soaks aute on an Armidale afternoon –

her work and her veins tying her family via Norfolk Island

via Pitkern

to Tahiti)

Vancouver who forty years later died in Petersham

(my Sydneysider Ngāpuhi friend Carleen

lived near Petersham

on Gadigal country)

which is in Surrey

(there’s a Surrey here too –

home of the fourth largest Indo-Fijian community in the world)

Vancouver mapped this Eastern edge of Oceania,

Becoming one of those white men who will never be obscure or forgotten

From here, when I look back towards home,

Hawai’i is in the middle distance –

Those complex supple islands where I repaired my waka

the other time I fled from home

Those staunch expansive islands

where love put Cook where he belonged

It’s already the fifteenth of February in Aotearoa

And the annual jokes about Cookery and love for Hawaiians

are day-old tweets

While here, today, it’s still the fourteenth –

The day to march downtown for lives and deaths of Indigenous women

But we’ve moved too recently with a daughter

too young to be kept safe in a pandemic

(As if this colony has ever been safe for Indigenous girls)

So I sit, scrolling, in a hired car and read

that New Zealand’s sixth highest mountain

is also called Vancouver.

I am trying to guess which maunga his name has smothered

and for how long,

I am undone, again –

By how much I have yet to learn about the place I am from

And how much I have yet to learn about this lovely drizzly place

With all these names that hang heavy,

obscuring the shape of the land.

So there’s a story of here to add to the story of not-there. But there’s also a story of among.

My own tiny insignificant personal geographic meanderings, and the particular circumstances in which I have made and remade decisions about where to live, to work, and to write, can also be seen in a wider two-centuries-long context of Māori mobility beyond Aotearoa. None of us is Kupe, and none of us is Captain Cook. Despite the ways we talk about ‘Māori’ in Aotearoa as if all Māori live within the political borders of New Zealand, no Māori person outside Aotearoa in 2023 is the first to hop on a waka and head (back) across the ocean. The number we usually kick around (especially with the help of work by the demographer Tahu Kukutai) is 20%: around one in five Māori people lives outside NZ. None of us who are Māori have no relations living outside New Zealand. In my own whānau, we have travelled all over the place in every generation – for love, for adventure, for education, for war, for mahi, to be further away, to be closer to somewhere else – for a purpose, a season, or a lifetime.

One of my favourite books of Māori poetry in the whole wide world is Robert Sullivan’s Voice Carried My Family (2005) because of the many ways he writes and rewrites stories of Māori mobility. Now, this is something I’ve spent a lot of time writing about in my academic writing: the Māori diaspora, or what – especially with a past Masters student and current collaborator Innez Haua – I have been starting to call ‘Diasporatanga.’ (Yes, LOL.) (Also, why not, eh. Another -tanga to add to all the rest.) Alongside Innez’s work, there’s also great Māori critical work about beyond-Aotearoa Māori experiences in academic publications but also in completed or in-progress theses by Jo Maarama Kāmira, Ngāwaiata Henderson, Karamea Wright, Sam Iti Prendergast, and Lou Glover.

With Innez, I am working on a special issue of a journal on ‘Diasporatanga’ (as you know, David, it started with a hiss and a roar then got slowed down due to the pandemic and, let’s face it, my decision to uproot myself and my family and doing the diaspora once again). We are committed to this being an all-Māori issue featuring academic and other writing by a wide range of Māori because oh my goodness are the academic opportunists ever buzzing around the Indigenous diaspora kaupapa at the moment. #buggeroff (Also, and yes I realise it’s rich or maybe contradictory for me to say this having spent more of my life in Aotearoa than outside, it also seems important for the issue to be dominated by Māori whose lives and experiences have been diasporic – the number of opinions and assumptions that some NZ-based Māori are happy to share about the Māori diaspora cracks me up especially when it comes from people who are keen to preach ‘nothing about us without us’ to non-Māori.)

Back when I was a PhD student (and planning to return forever) I lived one year in Hawai’i and got to know some of the multi-generational Māori community in Lā’ie – mostly through my dear Ngāpuhi friend AnnaMarie Christiansen who was born in Australia and raised in Las Vegas and who since 2003 has taught in English at BYU-Hawai’i. The community in Lā’ie is largely shaped by Mormon migration, a particular and fascinating thread of Māori mobility beyond Aotearoa that my PhD student Karamea Wright is tracing in her thesis. One day Anna and I were chatting about the Olympics (that were about to start) and even though I knew she was American I was still confused about why she wasn’t automatically backing the New Zealand team. ‘Alice,’ she said with a laugh, ‘you have yet to understand the difference between home and homeland.’

I have thought of this a lot over the years. Hanging out with diasporic Māori who are invested in Aotearoa but not necessarily New Zealand makes more visible to me the ways in which Aotearoa-based Māori (including myself, often) can end up somewhat over-investing in New Zealand. This over-investment might look like paying too much attention to the machinations of the state but might also involve naturalising the boundaries of the state by thinking about Māori who live outside New Zealand’s borders as being ‘not home’ as if a Taranaki person wouldn’t also be ‘not home’ in important ways in Katikati, Gisborne or Christchurch.

Anna isn’t the only literature-minded Māori person connected to Lāie; a Māori/ Hawaiian/ Samoan student who she taught as an undergrad at BYUH, and who I had the pleasure of supervising for a masters in English several years ago, Norman Thompson III (known to most of us as ‘T-Man’) recently graduated from Uni of Hawai’i with a PhD in English and currently teaches literature at the Hawaiian school Kamehameha. Decades earlier, Ngāti Toarangatira poet, foundational scholar and painter Vernice Wineera had been living in Lā’ie (where she is still based) when she published the first (and incredible) collection of poetry in English by a Māori woman, Mahanga (1978). A year after Mahanga appeared, Sydney-based Evelyn Patuawa-Nathan – who had written an article on Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira in Te Ao Hou in 1960 – published the second such collection, Opening Doors, in 1979 through the Fiji-based South Pacific Creative Arts Society.

I have spent a lot of time writing about, teaching and sharing the work of Wineera and Patuawa-Nathan, but of course they are only two of so many ‘long-distance’ Māori writers… from all the way back in 1817 when writing by Mowhee, who I believe to be our first published writer, was published in London (where he had been living in 1816 when he passed away after a life lived in Aotearoa, Norfolk Island, Australia and London)… and all the way through decades and latitudes and longitudes up to the many current Māori writers publishing their work all over the place.

Some of our most prolific contemporary writers and editors have written at least some of their work ‘there’ (not-Aotearoa): Hinemoana Baker, Vaughan Rapatahana, Anne-Marie Te Whiu, David Geary, Witi Ihimaera, Robert Sullivan, Lani Wendt Young, Paula Morris. If you read the contributor biographies in any Māori anthology – but especially, perhaps, the Huia collections, you’ll find that Māori people have been producing amazing work all over the place. Just this year, we have treats in the form of recent and forthcoming published books of poetic treats from Sydney-based Daley Rangi (Te Ātiawa) and San Francisco-based Nicola Andrews (Ngāti Paoa). (It would be remiss of me to not mention that many ‘long distance’ Māori writers are Takatāpui; to say this another way, not reading long-distance Māori writing could mean missing out on writing from and about all kinds of diverse Māori experiences other than, or alongside, diasporic ones.)

Okay and there’s a fourth way to tell this story. I’m not there in Aotearoa, I’m here in Musqueam, I’m among so many other long-distance Māori writers. But I’m also connected, through marriage and my daughter, to another Indigenous ‘here.’ This is a personal kind of reckoning with what it means to be a long-distance writer – but this is more about the futures to which I am committed rather than the journeys that brought me to this place in 2023. One central element of the decision I made eleven years ago to marry Vula was an acceptance that he is as deeply connected to his whenua in Fiji (specifically, he is from Macuata – his tūrangawaewae is Vunikodi at the far northeastern point of the motu of Vanua Levu) as I am to mine. We spoke about the stakes of what it meant to weave together our whenua/ vanua: there is no place we can live where we would both be home; any children we may have would not only be affiliated to where each of us comes from; we knew we couldn’t say ‘I do’ unless we were both totally prepared to not live on our own whenua again.

Living away, for me, is connected to having hooked my waka to another Indigenous person and, by extension, his whenua. On the one hand, this is a deeply personal aspect of my away-ness but on the other hand I bring it up because it might connect to broader questions about Māori people writing from long distance. It can feel like our conventional ways of thinking about indigeneity – and Māoriness specifically – too often quietly assume that (New Zealand) Māori is the only Indigenous show in town.

In reality, lots of Māori writers (both in and beyond Aotearoa) are in the position of my daughter who stands comfortably in Aotearoa and in her other Indigenous home. I wish for Titilia confidence in the whakaaro expressed in Wineera’s poem ‘Heritage’ that ends with lines that have deeply shaped my thinking about being Māori: ‘I am taking my place/ on this vast marae/ that is the Pacific/ we call home.’ To add to the usual long list of ways I fear I am failing to perfectly parent my daughter, I recognise that by moving here I have also removed her from whenua, whānau, opportunities to grasp and strengthen te reo, and so on. I do feel these things keenly, and worry about them a lot. I accept she may never live in Aotearoa again. Funnily enough, moving here was the final kick I needed to get myself organised with officially registering myself (and therefore her) in a couple of our iwi to which I have known my affiliation and did always intend to get the paperwork sorted to add to the ones I’d sorted earlier. But being away and considering what threads of connection I need to leave has placed a different kind of significance or urgency on that stuff. On the other hand, I have just finished prepping for her sixth birthday and although she and I may be the only ones at her party who know how to sing hari huritau ki a koe (despite the dreams I held six years ago of her future Māori world), her Indigenous world is more expansive than I could have imagined when she was born, let along when I was a child. At her party tomorrow she will play with Indigenous mates from Sherpa, Uyghur, Yaqui, Sto:lo, Tongan and Fijian backgrounds. And, being who she is, she also has the need and privilege of singing happy birthday in Fijian too.

I am keen to hear more from you, e te whanaunga. I have been thinking about the really different three ways we have met, according to my recollections anyway: one, the time spent writing together and hanging out that year you were at Vic when I was still working there and you were based at the International Institute of Modern Letters (IIML); two, the time I visited UBC to give a talk in History and we did a reading (my poetry and your play) together at the Longhouse here on campus; and three, here now that we live in the same town again – but due to so many things we have actually only been in the same place once and that was when Tayi Tibble came through for a writing festival and we met ahead of time to grab coffee; afterwards we took Tayi for bagels. Like, what do we make of these ways and places we have connected as – and with – writers?

DG: Yes, we met in 2008 at Te Herenga Waka at Vic Uni when I was Writer-in-Residence. I loved the $5 lunches and the chance to hang out with smart/funny Māori like you and Pauline Harris (and chatting to her about navigation and honouring Matariki – and look at it now!). I did two Continuing Ed courses while there. Great ones with Peter Adds on the treaty and Everard Halbert on te reo – me trying to close the gap again. Then, yes, you organized a gig while visiting at UBC and I dragged you off to see the wild Wim Wenders 3D tribute film to German modern dance legend Pina Bausch. Then we found a really noisy Irish pub and shouted at each other for a few hours. And now you’re back, but we both have kid commitments, and stay in touch via socials. But you were also talking about creating something to do with the diaspora. But we got busy. So this chat seemed like a chance to kick that off here.

Perhaps being a long-distance Māori writer/academic is also just staying in touch, seizing the brief windows, and flicking on opportunities.

And now back to the line between engagement and appropriation/extraction being perilous. I keep reminding myself, and others, that I’m #freshofftheboat, a relatively new immigrant – now citizen, one who’s benefitting from a colonial history that’s displaced and destroyed Indigenous peoples here. I like the acronym: W.A.I.T = Why Am I Talking? I ask myself that all the time in any discussion of Indigenous matters here. Is there someone better to speak on this? Can I find someone if they’re not in the room now? It’s part of trying to be a good ally and recognising/acknowledging the distance.

Another interesting thing to me is how what’s happening/happened in Aotearoa can seem idealised by some here.

ATPS: YES AMEN. I feel this whole point in my bones. I am saddened and maddened by the narrative about how Indigenous everything is paradise in Aotearoa – I don’t think the narrative is helpful for them or us.

DG: I end up having to set the record straight. I often end up saying that things are simpler in Aotearoa because there’s one Māori language with some dialects as opposed to British Columbia’s 35+ unique languages. Plus, the percentage of those who identify as Māori is more than three times that of those who identify as Indigenous in Canada. And there’s no French/Quebec sovereignty issue in NZ. And if you put people on a plane they can all be at a hui in Wellington within two hours. Distance is a much bigger issue in Canada.

So as a long-distance Māori I sometimes take on the role of ‘Fact-checker’ when others make assumptions about the progress Māori have made. Then, often, I head home and check my facts furiously because I sweat that I just added to the misinformation.

On the other hand, there’s no one like Taika Waititi in Canada, with his abilities to shapeshift and play trickster across the film and TV world. And APTN Aboriginal Peoples Television Network is a channel very few Canadians would ever engage with versus Whakaata Māori TV, which has secured a place in Aotearoa. So, nah, yeah, I do end up comparison shopping/commenting and fact-checking as that’s what having a foot on either side of the Pacific enables you do, while also acknowledging that you’re getting stretched very thin somewhere in the middle there and about to burst an embarrassing seam in your jeans that will put your nono on display to all.

DG’s Long Story Part II: The Happy…ish Ending. Magical Coincidences/Guidance from Ancestors/Whatevs

I’m not a terribly spiritual person. As a general rule, I don’t ‘feel’ things. When we finally took our tokotoko back to Taranaki we were welcomed home by the Komene family: Roy, Phyllis and Norma. Roy gave us a deep reading of our tokotoko, what each section meant, and how it connected us to our ancestors. We stayed the night with them at Puniho Pā. My cousin Neil woke in the middle of the night feeling he was being visited by tūpuna. He sobbed. He was overwhelmed and overjoyed that after all this time, 150 years, Etahi’s tokotoko and her wairua had come home with us, and was reunited with her people. And, me? I got nothing.

That’s okay. I may not ‘feel’ things, but I am aware that something otherworldly guided me to this point – closed the gap. Maybe that’s why I wanted ‘Hareruia’ to be ghost story – about the spirits that float around Taranaki – and because #Taika said too many Māori stories have ghosts in them. Which I took as a wero.

I went to the NZ Drama School 1986/87 before it was called Toi Whakaari. We came out knowing a lot of showtunes and no waiata. However, at least one miraculous thing happened while I was there. There was a callout by a guy who wanted photos of drama class exercises to go with his new book. We wouldn’t get paid but we’d get free lunch! The book was slated to be in every school in NZ! As an icebreaker we got paired up with acting students from another school where we had to tell a story about our ancestors. I told my stock ‘convict/whaler buys Māori bride for sack of spuds’ story.

The stranger opposite me said, ‘No, that’s not right. Those potatoes were a wedding gift.’

‘How would you know?’

‘Well, you look like some of my cousins. I bet we’re related.’

No! Yes! Her name was Toni Gordon and her mother was Rhondda Geary, my father’s cousin, who I’d never heard of. So Toni and I set about organising a reunion to see if we could sort this story out, and hopefully add to it. So in 1995 in Portobello, Dunedin, 270 Geary relatives turned up. There were many cousins who’d hadn’t seen each other since being kids. It was a joyful time and we gained some more clues as to our whakapapa. Another lost Uncle, Kevin Geary, produced the tokotoko korero with two heads. This linked us back to the Nga Mahanga twins who’d founded our hapu/iwi. This helped another cousin we met there, Neil Jury, begin the tedious trawl through archives to find Etahi Taputai and William Geary’s sons had been given land in the Porikapa block in Taranaki. We were on our way home.

But that initial meeting of Toni and me was so random, I like to think we were guided on that journey. And we met when we were ready, and our job is to keep building the relationships that Etahi lost – to shorten that distance for us, and others who follow. In that way our kids and their kids don’t grow up like we did. Part of that is learning our history but it’s also about who’s in our whanau now. Here’s a photo of some of my new cousins who followed us home to Taranaki at the entrance to Ōakura Pā.

And below is a photo of the ‘Geary’ name, among many others, at PKW (Parininihi ki Waitōtara ) which is where all the shares for the land that belonged to Etahi’s sons ended up. And mean that we have access to study grants from PKW. We made it back to the mountain.

And when I write a story like ‘Hareruia’ I hope in some small way it might help close some gap for those relatives of mine that read it. As Paula mentions in the Hiwa introduction, my story was inspired by the news that the school history curriculum was being overhauled to include more Māori content, because there was a gap – a huge frikkin’ gap! My story includes Titokowaru and Parihaka, but also Hāwera writer Ronald Hugh Morrieson, Leonard Cohen, and Buddha. Well, someone on the path to Buddha, and #enlightenment, but knowing they’ll never quite make it. And that’s okay. Cue ‘Bodhisattva’ by Steely Dan.

ATPS: I know you just wrapped things up nicely, but I wanted to have the last word. I just wanted to thank you for inviting me to be in conversation with you. Thank you to Paula for creating the space for you and me to kōrero in this way. It is such a thrill to get to offer a small contribution (albeit personally therapeutic/ navel-gazing at parts) to a celebration of a new anthology of Māori writing. And, congrats on the publication to you e te whanaunga – and to all of the writers, and to the editors and to AUP. Who knows what wonderful pathways each of these stories will now journey on… who knows what Māori writers will read Hiwa and think yep okay I’m now keen to write/ publish/ edit/ teach/ read more. Who knows who will see the stories in te reo, or in English, and feel newly encouraged or challenged or excited about tuhinga Māori. Ka mau te wehi! Kua tae mai a Hiwa! #yay

'Many of our best stories profit from a meeting of New Zealand and overseas influences' - Owen Marshall