Back to the Book Awards

The last sponsor abandoned them, but David Larsen finds that reports of the death of our national literature awards have been greatly exaggerated.

As one would expect, the media were all over the inaugural Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, held in Auckland on 10 May. I am obviously referring to the social media. The morning after the awards ceremony, writer Linda Burgess pointed out (on Facebook) that the New Zealand Herald’s top stories that day included ‘Antique Roadshow’s $74k error’ and ‘CBD-Panmure tunnel to bypass gridlock’ – but nothing on our new national book awards.

The Ockham New Zealand Book Awards are in their first year. Actually, they’re in their first year and a half, that being the interregnum period these awards needed to cover after the New Zealand Post Book Awards folded in 2014. This collapse should not have been a huge surprise. New Zealand Post had been hit hard by digital disruption, and a major arts sponsorship is hard to square with major staff redundancies. But it was a body blow for New Zealand writing and publishing. The country has had annual literary awards in one shape or another since 1968.

They’re gone, people said. That’s it. The sponsorship era is dead. We hadn’t counted on the zeal of Ockham Residential Limited, developers and self-described urban regenerators. ‘Why sponsor these awards?’ said Ockham’s Mark Todd at the awards after-party. ‘We want to improve the state of public discourse. Also, we give a shit.’

Meanwhile the Acorn Foundation, based in the Western Bay of Plenty, were looking askance at Tui’s 2015 Catch A Million competition. Cricket fans could win a million dollars for pulling off a one-handed catch while wearing the lucky colour of the day. A million dollars for catching a cricket ball, in the year no one was willing to fund our book awards? Through Acorn, some far-sighted anonymous donors endowed – in perpetuity – a $50,000 prize for the fiction award each year.

Still, even after the announcement of this new support, there was much discussion – on social media, at book launches, anywhere you were likely to bump into writers or publishers or critics – of who literary awards should serve, and how, and why.

One frequent lament was the lack of media splash, year in, year out, once the awards were announced. Media failure? Awards failure? Both? Both! And certainly, the old awards ceremonies were crushingly boring affairs. Plastic chicken was served as haute cuisine. The public was not invited, and the press as a rule turned up only for the chicken. (We’re not well paid.) The most notable coverage of the old awards’ 2014 Last Supper was one well regarded literary editor’s tweet, ‘I don’t even know what this is’. She was referring to the dessert.

So yes, it was reasonable to give the old awards some small share of the blame for the media silence they seemed to inspire. It’s not reasonable now. The failure of the largest newspaper in the country to notice that a well-designed, streamlined, public, highly entertaining ceremony had just launched a rather startling slate of award winners into the national literary firmament is not surprising – digital disruption is doing nastier things to journalism even than to the world’s postal services – but anyone who takes this as evidence that the awards organisers are doing something wrong is badly wrong themselves.

‘We’re lucky, aren’t we?’ said the pleasant elderly woman sitting next to me in the main auditorium of Auckland’s Town Hall, as the lights were going down. ‘To have such good writers’. She was responding to the full list of past awards-winners scrolling down the screen at the rear of the stage. It was a list worth seeing. Names I’m not well read enough to know. Harry Morton. John Dunmore. (He won in 1970, for The Fateful Voyage of the St John Baptiste. I had not yet learned to read.) Names any New Zealand reader knows. Janet Frame. Maurice Gee. Anne Salmond. Michael King. Edmund Hillary! The literary whakapapa of our country, or a good few of them. Awards are subjective, and fair only in their cumulative equality of unfairness; there is no way around this, and it’s silly to think otherwise. The winners list, many of them long dead, was still deeply moving. As a way of saying, ‘These awards matter; writing matters; be glad you’re here’, it was a well-judged overture.

The full ceremony took under ninety minutes. I’ve sat through ninety-minute Hollywood thrillers that felt longer. Awards Trust chair Nicola Legat opened, coming on stage briefly for the necessary thank yous and hat tips, one of the many this-must-be-done items which have doomed previous ceremonies to a funereal solemnity. She said what had to be said (sponsors! we love ‘em! politicians who turn up to our awards! they gladden our hearts!) economically and gracefully, a difficult pair of adverbs to combine, and got off the stage.

The MC, comedian Michele A’Court, was ‘fine’, which sounds like damningly faint praise. But fine was in fact the exact right thing for her to be: funny but not hilarious, diverting but not under the impression she was the main attraction. She made a few jokes, gave a clear and concise outline of the evening’s shape, and mentioned that at the end of the evening, all the books on all the shortlists would be available for purchase. This has never been the case at an awards evening before, partly because members of the public have never previously been let through the doors. Think about that a moment.

Maggie Barry, Minister for Arts, Culture & Heritage, announced the best first book awards. Offering a politician possession of your stage and a microphone is death, death, death. To the astonishment of all present, the Honorable Barry just did the job – only getting one winner’s name wrong.) The Judith Binney Best First Book Award for Illustrated Non-Fiction went to Richard Nunns for Te Ara Puoro: A Journey into the World of Māori Music. (He was ill, and his publisher, Robbie Burton, collected the award for him). The Jessie Mackay Award for Poetry went to Chris Tse for How to Be Dead in the Year of Snakes. The Hubert Church Award for Fiction went to David Coventry (or David Courtney, according to Barry) for his novel The Invisible Mile. The E H McCormick Award for General Non-Fiction went to Melissa Matutina Williams, for Panguru and the City: Kāinga Tahi, Kāinga Rua. It’s taken you longer to read this paragraph than these awards took to give out: bam bam bam bam, names announced, writers whisked on and off stage, done.

People I spoke to afterwards felt this was one of the moments of over-correction away from the languorous pace of the old awards. They wanted these writers to have mike time. ‘Some joy would have been nice,’ said one industry long-timer. It’s a reasonable point. I can only report my own reaction: ‘Adrenaline high, four awards in three minutes, awesome.’ It struck me as a well-calculated timing sacrifice: pare the four junior awards down, focus attention on the major awards, keep things moving. The desire to give everyone their time at the mike is admirable, and so is the desire to hold the audience right through the evening. Pick one.

The four major categories were handled very differently. For each, the four shortlistees were brought up on stage. In alphabetical order, each read a self-selected two-minute passage from their book, and sat down again with the audience. Then the convener of the relevant panel of judges – different judges for each category, a remarkably sane reduction in reading load from the old system – announced the winner and read a citation. The winner returned to receive the award.

This system is excellent. Everything about it is elegant, simple, and useful. There is an inherent risk in asking writers to read aloud, which is that not all of them can, but that in itself can be an interesting thing to learn. As it happened, the writers in three out of the four categories were solidly in the acceptable to excellent range as readers of their own work. Rachel Barrowman, reading a passage from her Maurice Gee biography in which the young Gee tries and fails to save a man’s life, and Witi Ihimaera, reading about his first few days at school and his grandmother’s stern response to Pakeha teaching, could each have been reading the kind of novels you’d run right out and buy; both of them were in fact shortlisted in general non-fiction.

Chris Tse and Tim Upperton, each reading their own poems, were arresting and entertaining in diametrically opposed yet similar ways, Tse dramatically understated, Upperton wry and laconic. Only the novelists, with the notable exception of Patricia Grace, failed to lever their books off the page and into the air. Even with the inevitable few weak readers, I cannot think of a better way to give an audience a sense of the quality and weight of the writing we were all there to celebrate.

The one clear error the organisers made was in the presentation of the illustrated non-fiction readings. One of the shortlistees, Athol McCredie, had asked to present a slide show from his book, New Zealand Photography Collected. ‘The photos are the substance of the book, they speak a visual language’. It was gorgeous, and it was essential. It became instantly obvious that the other three finalists should have been urged to take the same approach; getting the text of their books without the images was like being read the recipes in a cooking competition without being allowed to see the finished meals.

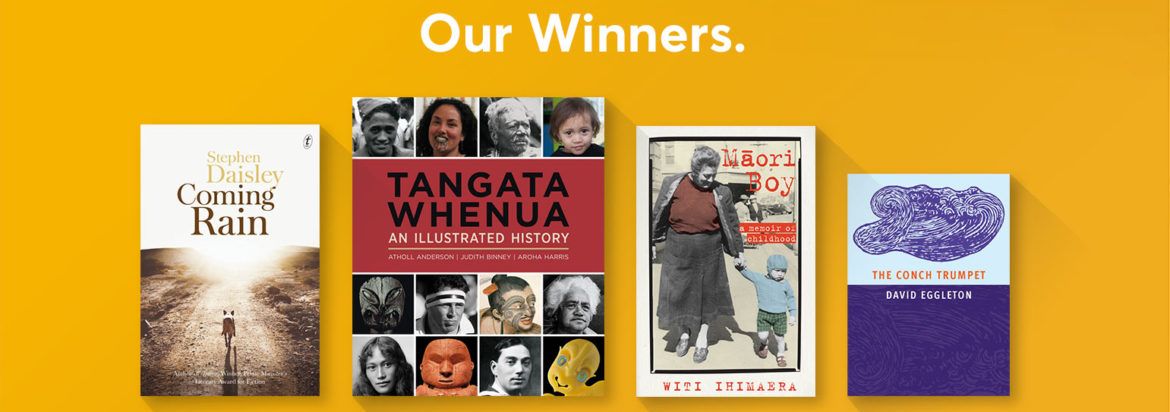

The winners in the four categories were Witi Ihimaera (Maori Boy: A Memoir of Childhood, Vintage) for general non-fiction; David Eggleton (The Conch Trumpet, OUP) for poetry; Judith Binney, Aroha Harris and Athol Anderson (Tangata Whenua: An Illustrated History, Bridget Williams Books) for illustrated non-fiction; and Stephen Daisley (Coming Rain, Text Publishing) for fiction. All four decisions were succinctly and eloquently explicated by the judges, which is the most you can ever ask; I doubt anyone in the room agreed with all four of them, because no one ever does. (Part of the social function of awards is to put pegs in the ground for subsequent literary arguments).

All four writers – Athol Anderson spoke for his team, Aroha Harris having done their reading – gave brief acceptance speeches. Daisley’s was my favourite. He was handed the golden Acorn and a cheque, and looked like a man who couldn’t believe he had just won fifty-thousand dollars for doing something he loved.

The great, much-missed New Zealand writer Nigel Cox once said that literary awards are a game. You have to take them seriously, or the game doesn’t work; but you mustn’t take them seriously, because it’s only a game. This is the most useful and sophisticated point of view I’ve encountered on the subject. My own point of view, heading from this awards ceremony into the Auckland Writers Festival for which they serve as curtain raiser, is that New Zealand’s literary awards have finally got the rules right.

David Larsen is a freelance writer based in Auckland.

'I started to feel very guilty, as though I’d perpetrated a crime, a rort' - Stephanie Johnson