Kevin Ireland, Gentleman Poet

A tribute by Johanna Emeney

The death of Kevin Ireland OBE on 19 May 2023, just two months short of his 90th birthday, is a deep loss. Kevin was a talented and prolific author, whose legacy of poetry collections, memoirs, short stories and novels is testament to his great skill as a creative, and to his dedication to the writing life. That he was able, in his late eighties, to write and perform his poetry so energetically, and that he was visible in his much-loved Devonport community until the last few months, will have made his death a terrible shock for many.

It seems almost impossible that we will not hear from him again. Kevin Ireland will be greatly missed, both as one of Aotearoa’s literary icons, and as a person who took a genuine interest in helping and encouraging emerging authors. What follows is a personal tribute to Kevin, based on one grateful recipient’s experience of his kindness and mentorship.

Chris Cole Catley organised a meeting between me and Kevin Ireland one afternoon in 2009. She had been promising to introduce me to one of my poetry heroes for some time, but I hadn’t expected something quite so impromptu. Ten minutes earlier, she had rung to tell him she was bringing her ‘new young poet’ over for a cup of coffee. Chris used to do a lot of telling. There was never much advance warning.

When his front door opened, Chris gave Kevin a quick kiss on the cheek, and then she started walking back to her car. ‘I’m just going to pick up a few things. You two enjoy!’ she called. I burned with embarrassment, and I could see that Kevin, too, was feeling a tad uncomfortable with the situation; he stood at the open door, staring at Chris’s back.

We muddled through the first five minutes, stumbling around shyly for things to talk about while Kevin tried to locate milk and sugar (he took his coffee black), and then, thank goodness, we were off, England and animals filling half an hour before Chris returned with her shopping.

After this initial meeting, Kevin offered to go through the whole manuscript that I had submitted to Cape Catley; he worked with me on it for months. He gave the speech at my launch. I still have no idea why he did all this other than his innate generosity and kindness. Kevin blessed other fledgling writers in this way. In fact, when talking with his wife, Janet Wilson, the week after Kevin died, I remarked that there must be many people who felt as I did — so grateful to her late husband for his faith and mentorship. Janet replied, ‘Well, that’s what he did for me, too. He gave me confidence in myself’.

If you ever saw Kevin at a double-launch, where his book was being celebrated alongside that of another poet, you may have noticed how he was never one to steal the spotlight; he frequently made more of the other book, or praised and bantered with his colleague on stage, making the event a real two-hander. I used to love going to such events — not just to hear Kevin read, which he did consummately, but also to observe a master class in how to treat others. Every card I sent him over the years was addressed to Kevin Ireland, Gentleman Poet, because that was how I perceived him, equally the brilliant poet and the perfect gentleman.

Kevin made the people he liked feel seen and special, whether it was by sending a copy of his newest collection pre-launch or simply by writing something lovely in response to an email. However, the fact that Kevin was, at heart, a self-effacing person made anyone harbouring a large ego or an overweening ambition seem strange and amusing to him. Self-aggrandisement was anathema to Kevin, and he had some wonderful jokes and asides about the literary circle’s arroganti. That’s not to say he was mean; his comments were simply apt, witty, and, often, wonderfully well timed. He could also direct his sense of humour mercilessly on himself, particularly as age made for the odd infirmity. I recall once talking with him on the phone after he had fallen down outside New World in Devonport. I asked him if anyone had helped him up. ‘No,’ he said, ‘But a couple of schoolgirls stopped to have a good laugh. Silly old fool.’ I was so upset by this. One of our taonga poets on the ground, and kids laughing? No one helping him up? There was no indignation to Kevin’s response; he was simply annoyed at his body for starting to betray him.

From his mid-70s, Kevin used the body’s failings as fodder for his poetry. Alongside love, friendship, poetry, fishing and dogs, health and aging were right up there as key Ireland themes. What I think is so admirable in Kevin’s writing is possibly what was so admirable in Kevin the man: the poems are so unassuming and yet so deeply layered. With the exception of one or two intentionally hefty works like ‘A Fine Morning at Passchendaele’ written in 2017 for the 100th Anniversary of the eponymous battle, Kevin’s poems are often talky, confiding; they have the laid-back air of riffing on a theme at a dinner party. It is only when you stop to study the metre, the turn of the lines, the nuanced phrasing, that you can appreciate the care with which they have been crafted. There is also a beautiful spirit to the poems — most usually a golden optimism, and sometimes an insouciant rebelliousness.

In his first memoir Under the Bridge & Over the Moon (Vintage, 1998), Kevin sums up his attitude to non-conformity:

The truly valuable side to non-conformity is that it is as irresistible as the grass that has the power to crack a concrete pathway. It splits the dull appearance of our best efforts to crush and conceal the anarchic aspects of our humanity. Yet its reward is seldom more than the private satisfaction of knowing that it can be a privilege to fill your mind with free thought, even at the risk of being in the wrong yet again — though I suppose it’s always a consolation to believe you’re wrong for the right reasons.

Kevin’s views on things always appeared to me to be liberal, and for the underdog. He didn’t like unfairness, and he despised a bully. Poems about Kevin’s childhood are few, but they are among the most poignant of his oeuvre because they describe it as ‘an experience/to be endured then never talked about’ — never talked about that is except with his younger brother Anthony who predeceased him in 2013 (‘Family Types’, Shape of the Heart, Quentin Wilson Publishing, 2020). In ‘Family Types’ Kevin describes the two brothers sitting in Anthony’s shearing shed, having one of these conversations:

just the two of us, sharing a sad joke

or recollection of unkindness we’d carry

with us to the grave. The subjects

that we could mention only when alone

seemed slight, but each held poison

we had learnt to deal with safely.

You get to handle lethal instabilities

and deadly menaces in families.

His memoir gives many insights into the violence and unhappiness of Kevin’s youth, but what stands out is the resilience of the little boy. Kevin’s resilience was a constant until his 89th and last year. I phoned him on the way to a poetry reading in Devonport, in December 2022. I thought I might pick him up on the way and we could go together and watch. For once, I didn’t get an ebullient reply. Instead, Kevin was rather flat. He was recovering from a recent surgery, and he didn’t feel up to much of anything. He told me he was getting fed up with getting older and the toll it was taking on his body. Then, he rallied. ‘Don’t stop asking,’ he said. ‘Absolutely lovely of you to ask.’

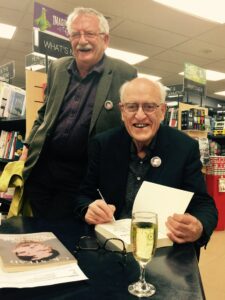

Kevin Ireland and C.K. Stead at Stead’s book launch of The Name on the Door is Not Mine. Photo credit: Johanna Emeney.

'...poetry makes intimate everything that it touches.' - Michael Harlow