Still Waters Run Deep

John McCrystal on the imaginative life and legacy of Maurice Gee.

The last time I saw Maurice Gee, he was literally wearing a grey cardigan. And slacks, and comfortable shoes and a wry, wary look. He was skulking (if that’s the right word) towards the back of a small-ish crowd attending a launch in our little, local bookshop. He blended in perfectly, and looking around the room, you might have mistaken him for the guy who would raise a tentative hand after the speeches and readings and politely ask the author where they got their ideas from.

I recognised him because I’d had the pleasure of interviewing him a week before. I was moderately surprised to see him, because during that interview, he had told me that he had pretty much nothing to do with ‘the book business’ anymore: whereas he’d always kept a low profile, he had now all but given interviews and festival appearances and readings away. His twelfth novel for adults – Ellie and the Shadowman – had emerged a matter of days beforehand, but this wasn’t his launch. I don’t recall whose launch it was, but Maurice, kind as ever, was there to show solidarity for a fellow author.

If there is a recurring theme in the press surrounding Gee, particularly in the latter years of his career and in the eulogism since his death last week, it is that he seemed so ‘ordinary’ (‘unassuming’, a ‘man in a grey cardie’) for someone who had produced such an extraordinary body of work. Damien Wilkins (who, curiously, I’ve always thought looks a bit like the younger Maurice Gee) has spoken and written about his resemblance to the archetypical (Pākehā) Kiwi bloke in early author photos: sleeves rolled up, ready for manual rather than intellectual labour. As he aged, he became indisputably avuncular. As he aged further, he began to look positively grandfatherly.

He looked mild and grandfatherly when I met him in person in 2001, and was moved to ask him, as so many interviewers had before me and have since, where he got his ideas from – those dark, haunting scenes in his writing featuring sex, violence, physical and psychological torment, and death. Sitting there in his cardie and slippers in his modest home on the slopes of Wellington’s Ngaio, he pretended to take the question seriously. It was only when I asked what his wife, Margaretha, thought of this kind of subject material that he raised an eyebrow and laughed nervously: Margaretha was in earshot. ‘You’d have to ask her,’ he said.

It wasn’t as silly a question as it sounds. Because while Maurice looked about as unlikely to inflict harm or do ill as any human being alive, he spent his entire writing life preoccupied by the evil that men (and women, but mostly men) do.

Maurice Gough Gee was born in Whakatāne in 1931 and shifted to Newington Road in Henderson — then a hamlet lying to the west of Auckland city — when he was an infant, the middle child of three brothers. He moved away from his childhood home in his early twenties, but psychologically speaking, he never really left. He acknowledged that his emotional landscape comprised the warmth and safety of home (especially the kitchen, his mother’s domain), and the chill and darkness of the larger (mostly masculine) world, as epitomised by the creek that ran past the Gee family property.

The creek gave him wonderful memories — an adventure he and one of his brothers had, descending from Henderson to the Waitematā Harbour in homemade canoes — but he also nearly drowned in it, and saw a young man fatally break his neck when diving into a swimming hole at low tide. In 2009, he told Stuff’s Grant Smithies that he ‘couldn’t seem to get away from Henderson Creek. It runs right through my imaginative life.’ And so it does. Anyone who has swum in murky water with a creeping sense of unease at what lies beneath will recognise the same sensation evoked in Gee’s work.

After starting out as a writer of poetry, Gee soon moved to short fiction, with many of his stories collected in A Glorious Morning, Comrade, published in 1976. By the time this collection emerged, he had already published two novels (which he later described dismissively as ‘apprentice novels’): The Big Season (1962) and A Special Flower (1965). Apprenticeship duly served, it was as a novelist that he was to make his name. In My Father’s Den (1972) won him critical acclaim and a publishing contract with the prestigious UK house, Faber, with whom he had a long and fruitful association. His fourth novel, Plumb, based on the character of his austere maternal grandfather James Chapple (and the first in a trilogy) was published in 1978 and is probably his best-known and most widely admired.

Between then and 2009, when Access Road, his last, emerged, Gee published a novel every two or three years, for a total of 17. Many won awards (including several incarnations of the top fiction prize), Gee held a number of literary fellowships (including the prestigious Menton fellowship in 1992) and was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in 2004. Few writers could boast they have had an entire literary festival named after one of their works (Going West). He was regarded as one of New Zealand’s best writers (if not the best), and hailed as a major figure in wider English letters: he was even mentioned as a possible nominee for the Nobel Prize for Literature — but it was thought that Janet Frame ought to be nominated first.

In genre terms, Gee was a realist. He was a master at evoking place and capturing the temper of times, even times that were not his own (Edwardian New Zealand in Plumb, New Zealand during World War II in Live Bodies). But it was people he did better than anyone. A man whom he befriended in the course of researching the nefarious business of property development for his 1994 novel Crime Story wrote to him that Gee’s ‘ability to see into people’s souls is becoming a bit frightening.’ This was acute, because that is precisely what his talent comprised: the ability to see human beings in the round, and then to capture them in his economical, limpid prose. Love, loathe, admire or despise them, it’s hard to see his characters as anything but real people.

This is certainly the way he saw them. When I talked to him about Ellie, the main protagonist in Ellie and the Shadowman, it was like discussing a mutual acquaintance; I was struck by how he spoke of her as though she were someone he had got to know rather than made up — as though there were aspects of her that baffled even him. Similarly, talking to an interviewer about the property developer character in Crime Story, for example, Gee said that he ‘didn’t like’ Howie, but there were some aspects of him that he admired. It may well be the case that his characters were made up of familiar and well-handled fragments of his own and of those of people he had known, but once he had stitched them together and thrown the switch to send the current of his imagination coursing through them, they fairly walked and breathed.

If realism was the strength of his novels, it was realistic fantasy that enabled Gee to forge an equally illustrious career as a writer for children and young adults. He published (by my count) 13 books for children, and won awards for these as well. While it can be presumptuous to declare anything to be ‘a classic’, a number of his children’s books are indisputably classics: Under the Mountain was acclaimed at the time (1979) and has endured, as has the trilogy comprising The Halfmen of O (1982), The Priests of Ferris (1984) and Motherstone (1985). Gee had the gift of taking his young readers seriously, probably because his own childhood still seemed so immediate to him. Even his fantastic landscapes feel familiar, and his characters find themselves in recognisable moral dilemmas. My 16-year-old daughter (who was stricken when I told her just now that Gee had died), appreciates the way he creates fantasy worlds in the New Zealand landscape (‘I wish I had a pair of magic glasses!’).

And in Gee’s view, you’re never too young to experience creeping unease. The creek! The malevolent wilberforces gnawing at the earth beneath suburban tranquility! The darkness in humanity of which children are mostly, but not completely, innocent. Gee understood the way young people confront and make sense of the world, something I felt when reading his 1990 (adult) novel, The Burning Boy. There is a scene where teenaged Hayley meets her boyfriend (who physically attracts and morally repels her) at a swimming spot, Freak’s Hole. She gives Gary a handjob as they bob about in the pool, but is suspicious as to why he has invited his two unsavoury friends along as well. Her fears are realised when the three boys attack her. She fights her way out of the situation, but afterwards it hits her how dire the danger is that she has just escaped. I recall how alone she seemed to me as I read it, negotiating the possibilities and perils of the world.

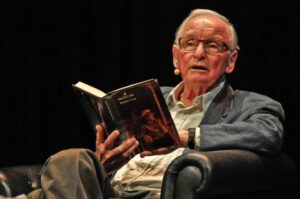

Maurice Gee reading from Prowlers at the 2012 Auckland Writers and Readers Festival. Photo credit: Gil Hanly.

It’s hard to say how Maurice Gee’s oeuvre will cellar. Perhaps his junior fiction will endure, as the update Under the Mountain was given in Jonathan King’s 2009 movie would suggest. As for his adult novels, it’s harder to say. Even in his prime, he was becoming unfashionable. Realism was ceding ground to post-modernism and experimentation with the form, such that Gee’s novels look conventional to the point of being old-fashioned when viewed through a contemporary lens.

What’s more, I was always surprised that whereas Owen Marshall seemed to attract the label of ‘provincialism’, Gee largely escaped it: he was unashamed of the ‘New Zealandy’ settings and sensibility of his fiction. But the New Zealand with which he was familiar and to which he returns in his fiction again and again has all but vanished, too. He grew up in a broadly conformist society, for the most part deeply sectarian, where even if you rejected religion (as Gee did), this was still to define yourself in relation to it. The New Zealand Gee grew up in seems somehow closer to George Plumb’s reality than to our own. By the mid-1980s, we were becoming conspicuously secular, and this trend has accelerated. Morality itself may have shifted. Gee was often accused of ‘puritanism’ and ‘moralism’.

I asked him if he considered his outlook to have been shaped by puritanism, but we ended up talking past each other. When in his memoir he described his young self as a puritan, he was referring to an adolescent’s horror of his emerging sexuality, and denial that there might be a female equivalent, whereas I thought I had identified in Crime Story a collision between the ‘decent’ communitarian values Gee grew up with and the flashy individualism that was emerging in the 1990s. (I thought I saw the same unease in some of the stories in Owen Marshall’s collection, Coming Home in the Dark, published around the same time: the crumbling of moral conventions as reflected in ‘Flute and Chance’ and the collection’s sublime and horrifying title story. Gee was intrigued by this hypothesis, but not convinced).

Karl Stead accused him of being too judgmental towards his own characters (as in the mingled dislike and admiration towards Howie referred to earlier). Gee himself said he ‘didn’t mind’ being thought of as a moralist. But I wonder whether this moralism itself will date his work, in a world that has only got flashier and more individualistic. And, of course, Gee was living and working in a New Zealand dominated by Pākehā men, and his work reflected his experience. As Ellie and the Shadowman showed, he was capable of writing the female perspective with conviction, but the bulk of his work is palpably masculine. In his fiction, he deliberately chose not to engage with the Māori renaissance that was gathering steam throughout his career, whereas more recent writers have turned to confront the shadow on the margins of New Zealand society, our colonial past.

Time will tell.

I would be hard pressed to name my favourite Gee novel. I admire Plumb (the book, and the trilogy, although I think I like the last, Meg, the most). Going West was one of the first I read, and would be up there. But I think, for me, Live Bodies was his finest work, where he simply nailed the character (of course) and especially the voice of Josef Mandl.

I would also commend Rachel Barrowman’s 2015 biography, Maurice Gee: Life and Work as a fascinating study in the alchemy by which a writer’s experience is rendered into fictional gold. Gee expressed satisfaction with it. And just as fascinating in light of Barrowman’s is Gee’s own memoir, Memory Pieces, not least for the intriguing choices he made as to what he included, what he left out.

Nearly a third of what is supposed to be his memoir is actually a telling of Margaretha’s story. The two were together for well over half a century, and Gee credits her with creating the conditions he needed to be as prolific as he was. She was never a ‘kitchen person’, he said, but she created the security of his childhood kitchen from which he could venture out to explore the creek. They made a wonderful match, and it is sad that it has ended. I loved the story Barrowman recounts of how Maurice and Margaretha sold their Nelson house to move into a retirement village, only to find they hated it. They managed to buy their house back again. (I loved that Damien Wilkins used the story in his 2024 novel, Delirious, and I’m sure Maurice would have been delighted, too). Gee often complained that he was ‘no good’ at endings, but it is the way of things that even the greatest of novelists, like all good things, must eventually reach an end. Maurice Gee was 93. Haere, haere, haere rā.

Read Sue Orr’s portrait of Maurice Gee here.

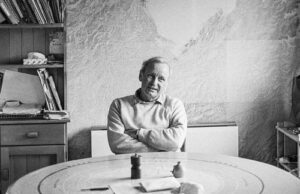

** Feature header image from Portrait of author Maurice Gee. Graham, Reginald Kenneth, 1930-2007 :Photographs of prominent New Zealanders. Ref: PAColl-6458-1-08. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23121102

'The thirty-five of us were in the country of dream-merchants, and strange things were bound to happen.' - Anne Kennedy