Takataka te kāhui o te rangi

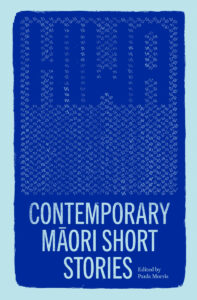

A new anthology, Hiwa: Contemporary Māori Short Stories, will be published by Auckland University Press on 10 August 2023, featuring work by 27 writers working in te reo Māori or English. It’s edited by Paula Morris (Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Manuhiri, Ngāti Whātua) with consulting editor Darryn Joseph (Ngāti Maniapoto).

The following excerpts are from the book’s introduction:

All over the world, storytelling began, and continues to exist, as an oral medium. As contemporary writers with Māori whakapapa, our inheritance is a tradition of shared stories and expert oratory. We also inherit a history of imaginative engagement with the physical and spiritual dimensions of lived experience.

The written story, with its varying forms and conventions, grows from this inheritance. As the written word spreads – through books, newspapers, journals, the internet – our stories reach more readers. They influence, inform and spark other writers.

After all, readers and writers connect with each other across oceans, cultures, languages and time. In the 1940s, when Gabriel García Márquez was a university student in Bogotá, a friend lent him a book of short stories by Franz Kafka, translated into Spanish from the German original. García Márquez read the opening line of the story ‘The Metamorphosis’, originally published in 1915, and thought ‘I didn’t know anyone was allowed to write things like that. If I had known, I would have started writing a long time ago. So I immediately started writing short stories.’[1]

Sometimes the journey is shorter in space and time, but no less vital. In 1955, J. C. (Jacquie) Sturm published an English-language story, ‘For All the Saints’, in Te Ao Hou, the journal published by the Department of Māori Affairs between 1952 and 1975. Sturm’s was the first story in the journal’s ‘Series of Short Stories by Māori Authors’.[2] A decade later, when C. K. Stead included ‘For All the Saints’ in New Zealand Short Stories, she became the first Māori writer to appear in a New Zealand literary anthology. Witi Ihimaera remembers reading the story as a teenager; its publication meant something seemed more possible, more real: a literary career for a Māori fiction writer.

Over time, literary descendants multiply: Gogol, writing ‘The Nose’ and ‘The Overcoat’ in Russia in the 1830s and 1840s, has an influence that travels via Kafka to South America – Borges as well as García Márquez – and to Japan, and onwards to some of the writers in this anthology. Gogol’s influence shimmers via Ernest Hemingway to Acoma Pueblo writer Simon Ortiz – an ardent teenage fan – and then to Sherman Alexie (Spokane-Coeur d’Alene), who first read the work of Ortiz as a university student. There’s a fluid line, too, from Gogol to Chekhov to Katherine Mansfield and, again, to this anthology. Short stories are the wily messengers of fiction, shooting potent darts around the universe and through the centuries.

Short stories are also works of art, each one an experiment and an adventure in language. In his introduction to The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories (2004), Ben Marcus describes stories as ‘language-made hallucinations, fabrications that persuade us to believe in them for their duration’.[3] The fabrication demands a great deal of its writer. ‘The task for me,’ Patricia Grace said in a 1998 speech given in Hawai’i,

is to put what is known, the body of knowledge that informs fiction, through a process – bending it, twisting it, bringing language to bear, bringing imagination to bear, bringing individuality to bear, bringing imagery and creativity to bear, bringing research to bear on it. During this process we attempt to push out the edges of understanding of what we know …[4]

All the stories in this anthology express the peculiar vision – and talents – of each writer, including their facilty with language. Each story expresses its writer’s individuality, as well as a heritage of sources, traditions and influences. And each story is part of a larger story: of what Grace describes as pushing out the edges of understanding. ‘Stories keep mattering,’ says Marcus, ‘by reimagining their own methods, manners and techniques. A writer has to believe, and prove, that there are, if not new stories, then new ways of telling the old ones.’[5]

* * *

The short story is often an entry point for fiction writers and the preferred medium of the writing contest and writing workshops. Since the 1970s, media like the New Zealand Listener and Radio New Zealand have published or broadcast stories by Māori writers. Many Māori writers have received their first recognition as writers through the Pikihuia Awards, a biennial competition that began life as the Huia Short Story Awards in 1995. Over the years the awards have expanded and contracted at various points, embracing and discarding different genres; there is currently a category for poetry as well as short fiction. A number of the writers in Hiwa: Contemporary Māori Short Stories have been Pikihuia finalists, with stories subsequently published in one of the Huia Short Stories anthologies: for many, it’s their first print publication.

In New Zealand today, there are many other opportunities to publish short fiction, from established literary journals like Landfall to the ReadingRoom section of the Newsroom site: in the past two years alone, its editor, Steve Braunias, has published work by thirteen Māori writers. Two of the writers in Hiwa, Shelley Burne-Field and Tina Makereti, have both been finalists for the Asia/Pacific region in the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, organised from the Commonwealth Foundation (an intergovernmental organisation based in London); when the competition was for books, my own story collection Forbidden Cities was a regional finalist. The annual Sunday Star Times Short Story Awards – forty years old in 2023 and a coveted prize – now also has an Emerging Māori Writer category.

Although it is received wisdom throughout the English-language publishing world that books of short stories have lower sales than novels, several of the emerging writers in this anthology – Jack Remiel Cottrell, Emma Hislop, Anthony Lapwood, Colleen Maria Lenihan and Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall – have recently published debut collections, albeit with independent or university presses. Pūrākau: Māori Myths Retold by Māori Writers has defied the odds, in that it is an ongoing sales success: it has had twelve reprints in three years.

One obvious change from a landmark anthology like Into the World of Light, edited by Witi Ihimaera and D. S. Long, published forty years ago: New Zealand is now awash in creative writing programmes that offer opportunities to study the art and craft of writing. Twelve of the writers in Hiwa are graduates of postgraduate degrees in creative writing from the University of Auckland, AUT, Massey University, the University of Waikato and, at Te Herenga Waka University in Wellington, the International Institute of Modern Letters. Three of us have similar credentials from universities in the USA and Australia. Five of us teach or have taught at one of these institutions. In addition, five writers have gone through the Te Papa Tupu mentoring programme run by Te Waka Taki Kōrero (the Māori Literature Trust); three of us have served as mentors on that programme.

The Covid era has disrupted many community writing programmes, and caused the long-term postponement of the biennial National Māori Writers’ Hui. But more craft teaching and discussion is now being made available online: for example, through the New Zealand Society of Authors’ webinar series. Writers no longer have to make their way to urban centres, or pay high fees, to study story-writing.

Wharerangi, the online Māori literature hub I launched in 2021, was created to help Māori writers access information about opportunities, including Māori-specific residencies at the Michael King Writers’ Centre in Auckland and the International Institute of Modern Letters in Wellington. In the past three years, two Māori writers – Becky Manawatu and Whiti Hereaka – have won the prestigious Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Three Māori writers – Manawatu, Rebecca K Reilly and Anthony Lapwood – have won the Hubert Church Prize for best first book of fiction. Another two Māori writers, Michael Bennett and Monty Soutar, were fiction finalists in the 2023 awards for their novels Better the Blood and Kāwai. The age-old obstacles for Māori writers remain, chief among them the need to make a living in a small market that cannot support literary careers. But openings for Māori to develop as writers and to publish our work continue to grow, along with our confidence and our skills.

* * *

This new anthology celebrates the season in which we are all writing – yet another time of growth for Māori writers and writing – in the hope that each year will be even more fruitful. The title is a reference to Hiwa-i-te-rangi, the ninth and final star in the Matariki cluster. In Matariki: The Star of the Year (2017), Rangi Matamua describes Hiwa’s name as

connected to the promise of a prosperous season. The word ‘hiwa’ means ‘vigorous of growth’, and it is to Hiwa that Māori would send their dreams and desires for the year in the hope that they would be realised.[6]

Hiwa and the star Pōhutukawa are ‘the most sacred of the group,’ Matamua writes, citing a manuscript about Māori star lore begun in the late nineteenth century by Te Kōkau, and completed by his son Timi Rāwiri in the 1930s. One star, Pōhutukawa, ‘is connected to the dead’ and the other, Hiwa, ‘deals with the deepest desires of the heart’.[7] Matamua quotes a karakia to Hiwa:

Takataka te kāhui o te rangi

Koia a pou tō putanga ki te whai ao

Ki te ao mārama.

Let the stars fall from the sky [my wishes]

And be realised in this world

The world of light.[8]

This anthology follows its predecessors by placing a stake in the ground. Here it marks the vigorous growth of story-writing by Māori writers in the twenty-first century, each of us building on centuries of precedent, both spoken and written. It also sends a wish soaring high into the night: for more writers to give the short story serious consideration, and for more readers to explore its artful pleasures and possibilities. More stories, more readers, more stars falling from the sky and taking shape in a world that is constantly re-written and re-imagined.

Writers featured in Hiwa: Contemporary Māori Short Stories:

Shelley Burne-Field / Jack Remiel Cottrell / David Geary / Patricia Grace / K.T. Harrison / Aramiha Harwood / Whiti Hereaka / Emma Hislop / Witi Ihimaera / J. Wiremu Kane / Earle Karini / Anthony Lapwood / Colleen Maria Lenihan / Nic Low / Tina Makereti / Becky Manawatu / Atakohu Middleton / Kelly Ana Morey / Paula Morris / Pamela Morrow / Airana Ngarewa / Zeb Nicklin / Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall / Rawinia Parata / Ngawiki-Aroha Rewita / Alice Tawhai / Nick Twemlow.

Footnotes:

[1] Peter Stone, ‘Gabriel García Marquez: The Art of Fiction No. 69’, Paris Review, Issue 82, Winter 1981, https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/3196/the-art-of-fiction-no-69-gabriel-garcia-marquez

[2] J. C. Sturm, ‘For All the Saints’, Te Ao Hou, December 1955, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/TAH195512.2.16

[3] Ben Marcus (ed.), The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, New York, Anchor, 2004, p. xv.

[4] Patricia Grace, From the Centre: A Writer’s Life, Auckland, Penguin, 2021, p. 201.

[5] Marcus, p. xiii.

[6] Rangi Matamua, Matariki: The Star of the Year, Wellington, Huia, 2017, p. 33.

[7] Ibid, p. 35.

[8] Ibid, p. 62.

'I felt energised by the freedom of 'making things up’' - Maxine Alterio