The Ockham NZ Book Awards: Fiction Round Table 2025

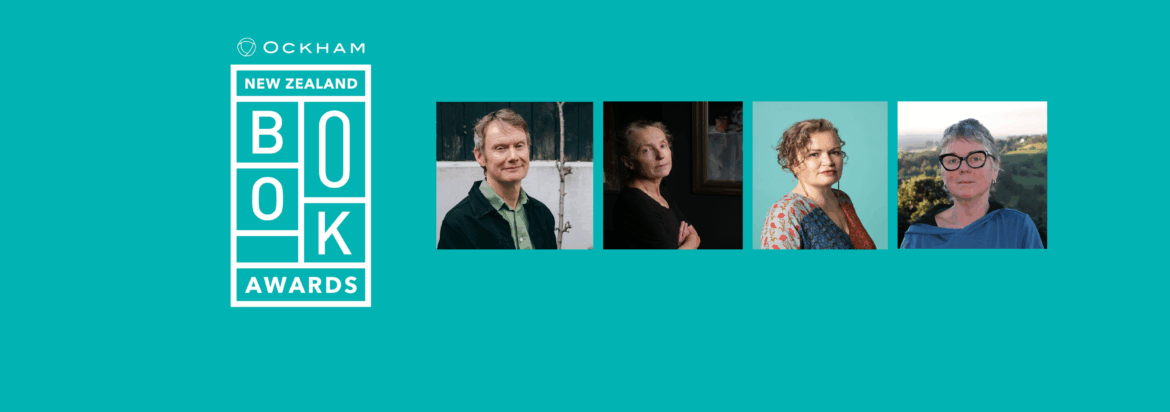

This year’s finalists for the $65,000 Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction are Laurence Fearnley (At the Grand Glacier Hotel), Kirsty Gunn (Pretty Ugly), Tina Makereti (The Mires) and Damien Wilkins (Delirious). Thom Conroy, convenor of the fiction judges, said: ‘Whether set in the Scottish Highlands, at the Fox Glacier, or on the Kāpiti Coast, each of these finalists evoked a visceral and often lyrical sense of place.’

Laurence Fearnley’s novel At the Grand Glacier Hotel is the third in a series based on the five senses: this book explores the experience of sound. A woman recovering from cancer surgery finds herself marooned in a historic hotel, cut off by a storm from her partner and the outside world. The novel, ‘set within the extraordinary environment of south Westland, is a riveting account of human frailty told with clarity and insight,’ wrote reviewer Sally Blundell. Laurence has won the overall fiction prize in a previous incarnation of the book awards, for The Hut Builder in 2011.

Kirsty Gunn last won the fiction prize at our national book awards in 2013, with her novel The Big Music. Her story collection Pretty Ugly is her third, and the inaugural title in a new short stories series published by Landfall and Otago University Press. It’s a book that reveals ‘an abiding imaginative and intellectual curiosity about the possibilities of storytelling’, John Prins wrote in the Aotearoa NZ Review of Books. The ‘stories in Pretty Ugly will enhance her reputation as revolutionary and help to expand the boundaries of Aotearoa’s contemporary literature into new and interesting places’.

Tina Makereti is shortlisted for her third novel, The Mires. It ‘is set in a post-lockdown, not-too-distant time – a wā that could conceivably be any day from now,’ Natasha Lampard wrote in Kete Books. ‘It is a story of what it means to be at home: in this world, on this body of land, this body of water. And what it means to be at home in ourselves.’ Tina’s first collection of essays, This Compulsion in Us, is published this month.

Damien Wilkins has published 10 novels over thirty years. Delirious, wrote reviewer Laura Borrowdale, ‘has a lot of what you’d expect from Wilkins – a book that’s about ‘something’, that has intellectual meat on its plot bones, beautiful writing, and a very, very New Zealand setting’. In the novel, a couple wrangle with the implications of aging, and the ghosts and grief of the past: they ‘must decide how much they let the past into their present’. Damien won the fiction prize at our national book awards in 1994, for his debut novel The Miserables.

The conversation – with occasional questions from Paula Morris – was conducted remotely in April 2025. All four writers will appear at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards on Wednesday 14 May, during the Auckland Writers Festival.

Paula: Welcome to our 2025 round table. You are all established fiction writers, authors of multiple books (with, in some cases, excursions into nonfiction as well). Would you each talk about your shortlisted book and how it follows – or departs – from what you’ve published before?

Laurence: Thanks, Paula. My novel belongs to a series I began in 2019 based on the five senses. The original idea came from walks on Signal Hill (Dunedin) and scent mapping the routes I took. I wanted to approach landscape in a new way – through scent rather than sight. Thus a visually ‘ugly’ area could be appreciated for its beautiful or complex scent. The original pieces I wrote were nonfiction (for the Massey University Press anthology Home and the Landfall Essay Competition (Landfall 234, The perfume Counter).

My first novel was Scented, then Winter Time (touch) and At the Grand Glacier Hotel (sound). The sound element comes through in both descriptions of the natural and human world, and also in silences. I’ve finished the fourth novel, Dedication, based on sight, and am working on Rivers (taste). I like writing detail, and am most interested in creating immersive (tonal, atmospheric) works where plot is secondary. So, the five senses project has been enjoyable for that reason.

Kirsty: I love what Laurence just said about using different senses. I do think that, as writers, it’s interesting to ‘sense’ our work differently with each project. That prevents it becoming stale, in my view – and keeps every new book of fiction fresh, a new idea, a new approach. With this latest collection of stories of mine, Pretty Ugly, I wanted to really test how far I could inoculate myself, as it were, against the horrors of late capitalism and a ghastly political situation that meant right wing thinking and authoritarianism was on the rise.

So I worked very deliberately to create stories with truly awful people and situations…as a way of thinking them through – allowing these awful things, as it were – and so protect myself, I suppose, and my reader – I hope! – against what was going on in the world…Is what I mean by inoculation, perhaps. To face up to this stuff – acknowledge it’s there, to think about it, that it exists – amongst the loveliness that is also this world. That deliberate kind of ‘making’, of fashioning something out of the contemporary situation that I could use for ethical purposes … That felt very new to me.

.

Tina: Kia ora tātou. I knew about Laurence’s series based on the senses, which I always thought was a very cool idea, and something I couldn’t imagine planning. It wasn’t until I had finished The Mires that I realised it might in fact be the final part of what seems to me to be a kind of trilogy that attempts to think through questions around racism, identity and community. Publishing The Mires felt like I’d come to the end of something more than just the book. I think I’ve come to the end of talking about identity and race head-on. I had thought I was writing very different things, but as our wise friend Lynn Jenner once said, ‘the end of one book is just the beginning of the next’.

But my novels are definitely three very different approaches to those kaupapa. I always want to do something technically different and challenging, and even though I have these big kaupapa questions, the only way to get at them is through character, so nothing can really emerge until they do. Where the Rēkohu Bone Sings is multiple-perspective, multiple timeline book that asks how we understand what happened to Moriori on Rēkohu through the experiences of five different characters; The Imaginary Lives of James Pōneke is a first-person account of a fictional Māori character who is taken to London to be exhibited, and encounters the savage world of early Victorian England; and The Mires is narrated by the roving perspective of the Swamp, who comes very close to the points of view of a group of characters in the very near future, as they grapple with the same tensions and dangers that we are unfortunately facing right now in a very real way.

Laurence: All your novels also have a very strong sense of place, and what it means to belong (or not) in that space, which is something I also found interesting when reading Damien’s Delirious. Both this and The Mires are set in the same part of the country, and they almost seem like companion pieces. Yours has a sense of majesty and vastness, a primal quality whereas Damien’s is more of a domestic-scale, human-ordered landscape, but they both examine community, and who gets to live where, and how to come to terms with being part of, or within, this land.

Damien: My previous two novels had dealt respectively with a young mother (Lifting) and a middle-aged father (Dad Art). I hadn’t ever told a story from an old person’s perspective. Immediately this makes it seem a bit cool and calculated. Really I was overtaken by a bunch of real life events which pressed against me and my writing. My mother had delirium which became dementia; my father had a stroke. The collapse of agency was startling. I mean, intellectually I knew it – bodies and minds fail – but it was suddenly all very personal. In this hideous three-parter, my older sister had died a few years before.

Delirious was where I tried to put a lot of this stuff. Not that it’s gone anywhere. I guess that your novel, Laurence, has similar pressures on it. The funny thing about making a novel out of this material is that although these strong feelings of pain and grief can seem all-consuming, they aren’t enough for the novel. You’ve still got to figure out things like scenes and a time-line and narrative shape and tone. You’re suffering but you’re also methodically working away at this strange craft.

Laurence: I’d reread The Pilgrim’s Progress when I was sick and became very interested in the idea of carrying a burden. That book deals with faith, and the burden of sin, but I was more interested in the aspect of a physical burden, or a burden that strikes the body, and how to negotiate that through going on a physical ‘walking’ pilgrimage, aided by a stranger. I’ve noticed my characters are aging as I’ve aged and I guess I’m more tuned in to decline (physical, mental). I’m wondering if writing about your personal experience, Damien, was cathartic in any way; if it helped you make sense of things that were happening to your family? Mine was the opposite experience; writing was pretty bleak. I put that down to what you were saying about making a novel out of life experiences. With a novel you have to re-work, edit, re-read, polish. While that might make for a better book, it doesn’t necessarily help with ‘pain’. But maybe it did with you? And Tina: Your novel deals with heavy issues and material and I imagine that must take quite a toll.

Tina: You’re such a generous reader, Laurence. I find there’s a paradox for me in the writing – it’s not really hard on me emotionally – it’s definitely more like being lifted out of the heavy place. Writing brings me such a sense of connection and elevation. It’s a place where I feel like I’m part of something so much greater than me. The hard stuff is always with me in everyday life, and sometimes research is shattering, so writing actually relieves the painful nature of being alive. I can be writing about the painful thing or not, and it works just the same. Very rarely, I write something that makes me feel angrier. Then I know it’s too fresh to write about yet.

I’m sorry At the Grand Glacier Hotel was difficult in that way, Laurence. Having said all of the above, I don’t know if I could write a whole novel about someone with cancer without finding it very difficult. Writing doesn’t leave many places to hide!

Kirsty: I’m interested in the way we all seem to be circling around this idea of making art – that is, writing our novels and short stories – alongside living alongside them, inside them … living our lives. That we are engaged in the business of what it FEELS like to make these books, what they’ve come out, where they seem to want to go. I love that. I love the idea of this kind of … living writing. That these are not books sitting over there, as ‘entertainments’ as Katherine Mansfield described that kind of writing.

No. These books of ours, as we are talking about them, are not spectacles in any way… But are part of our living, breathing worlds. Oh yes. That appeals to me hugely. That one can be a living writer, and not just some person who’s done the research, or who’s come up with the idea and now has a book to show for it. That we are all, instead, it seems, interested in this other thing, a kind of organic fiction.

Damien: I can’t say writing the novel was cathartic for me. (I’m envious about your feeling of elevation, Tina.) I am gratified that the novel has found readers and they felt something. Reading might be different. I remember reading Annie Ernaux’s amazing short memoir about the last period of her mother’s life, I Remain in Darkness. The title is a bit of a giveaway! She’s recording these details of her mother’s decline and her own difficult feelings about their relationship and she’s horrified by what she’s writing. She disowns literature, finds it appalling, a mistake. I found that oddly exciting. Yes, writing is a terrible mistake, now tell me more about your mother!

.

.

Laurence: I guess I have used so many life experiences in my work (notably my love/ gratitude for the remoter parts of the country) that it was almost a given that I would want to explore the experience of having cancer which I found absolutely fascinating, as it is a place where you truly find science, art, and craft in a kind of harmony. It was a beautiful thing, in that respect: meditative almost. I liked the solitude of it; it reminded me very much of writing.

One thing I’d like to ask you about is the notion of passivity, as it relates to characters. I’ve noticed that readers sometimes express irritation with characters that don’t seem to take action. They remark that they’d like to give a character a kick in the pants. But I feel that passive, inward-looking characters are very true to life. It can take a long time to process information, experiences, and it’s a choice whether or not you act. Being slow and thoughtful is not a weakness in my eyes. I was thinking of this reading both your novels, Tina and Damien. The sense of simply ‘carrying on’ and not changing course showed up, the reluctance to change…and the force to change is sometimes external, forced on the characters. I prefer to understand my characters (as they are) rather than move them around as chess pieces on a board and I sensed something similar reading your novels too.

Tina: I was challenged about this re: Sera in an early draft, and I did give her more to do, but I didn’t think her quietness was ‘passive’. I thought of it as a different kind of power. More meditative. Women need to rest when we can, and I liked giving this character who had been through so many horrors, the time and space to just be. This might have been influenced by my own experience with cancer, which became a kind of reckoning with all kinds of things. There was a lot of walking and doing as little as possible. Rest is resistance! (although, she has a toddler, so maybe not resting that much).

Kirsty: Going back to your point about interiority and lack of action, Laurence…Isn’t this one of the great pleasures of reading? In English language literature, at least? That glorious immersion in the inside of things…We start having access to that in Hamlet – thinking versus action – and take it from there. It’s a sort of education in imagination and thoughtfulness and developing depth of feeling. I love things not happening! But when they do – yes, that is interesting…But we need space around the explosion of ‘event’, is my view, I guess. We need the time that surrounds stuff happening on the page just as we need it in life. We need those seconds, minutes to pass…so we can think, feel, react for ourselves about it and not because the fiction has hurried us along.

Paula: Expanding on that idea of an ‘education in imagination’, what other writers and artists helped form your own (for each of you)?

Tina: Coincidentally, I had reason to check my PhD thesis from 2013 for something today, and I came upon this passage again, from Margaret Mahy’s wonderful essay ‘A Dissolving Ghost’ (1991): ‘She wrote of a “marvellous code” – something present in

all our lives, so deep-set and omnipotent that it informs everything we do and cannot

be dismantled. “Broken into bits,” she suggests, “it starts to reassemble itself like the

Iron Man described by Ted Hughes, and creeps back into our lives patient but

Inexorable […] I am referring to story, something we encounter in childhood and live with all

our lives. Without the ability to tell or live prescribed stories we lose the ability to

make sense of our lives.”’

There is an essay in my forthcoming collection, This Compulsion in Us, that talks about the writers and artists who influenced me early on, including: Alice Walker, Jeanette Winterson, Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, Keri Hulme, Merata Mita, my grandmother, NZ filmmakers of the 1980s, my father for letting me watch them, and Masterpiece Theatre! It wasn’t an exhaustive list – add to that, fairy tales, creation stories, Robyn Kahukiwa, Patricia Grace, Robert Jahnke, Toni Morrison. After that the list just expands ever outwards.

Damien: Circling back again to Laurence’s question about passive characters…I tried to work out what I thought in an essay on this very topic years ago. (It was republished in The Fuse Box, VUP 2017, next to one of Tina’s essays). I won’t rehash the argument but I do think passivity gets a bad rap. As Tina suggests, so-called passivity can be strategic and political. It can also, as Kirsty says, be another way of getting at interior lives. I connect it with the question of personal transformation and whether narratives are basically about characters who change. To escape that potentially coercive vocabulary (change your life!), I came up with something more modest, as in, I like to read about someone who has gone through something. A good novel makes us feel things more intensely.

I read all the early Jean Rhys novels a while ago. You couldn’t say that her lead characters are transformed – but I was a bit. Their stuckness was the point. And then somehow the power of the language lifted and consoled – consoled the reader, not the characters. If change can’t be firmly or credibly located in a character, I reckon the book itself is the site of change. That said, I don’t think there’s automatically something more ‘serious’ or even interesting about a character who mooches around. Everything in writing is earned. Laurence: I’ve just started reading your novel. (Sorry, catching up!) There’s a wonderful small moment when the narrator, who is recovering from cancer, apologises to her partner for the fact that the café where he’s left his glasses is closed. Of course it’s not her fault. And she thinks how she’s become an apologiser since her diagnosis. Such a beautiful and surprising insight! Already this character feels like good company – someone alert to the changed world.

Laurence: I suppose I have been drawn to early 20th Century American novelists like Edith Wharton (House of Mirth) or Henry James (Washington Square) for the depth of insight into character and the pressures of society that squeezes and constricts. Stylistically, I was a big fan of Robert Walser, Marguerite Duras, Patrick Modiano etc –those immersive, sensory, European writers.

I remember that Kirsty’s Rain made a big impact on me when I was starting out because of its atmosphere and tone, and later, when I was living in Germany I had a copy of Damien’s which I must have read three or four times, almost studying it in terms of craft. Later still, meeting Tina because we did our PhDs together, was a very special experience, notable for the depth and care you showed towards the lives and stories you told through your novel. It made me think very deeply about who owns a story, who gets to tell it, and how important it is to acknowledge and respect where ideas come from. It had a big impact on me when I was writing my novel Scented, when I was learning about the Grand Māori Perfume. I became very aware of my lack of understanding.

Tina: Oh my goodness, The Grand Māori Perfume? I am also very aware of my lack of understanding about this! I feel, not for the first time, that I may be the least well-read person in this virtual room, and humbled by the care and attention to fiction that each of you show. It’s like fiction gives each of us the opportunity to look at something so closely and deeply, and to turn it on different angles, and see how the light is refracted, or what shadows fall. I feel so lucky to be able to do that and to be in the company of others who do it. I am playing a very long game of catch-up, but I did read Middlemarch for the first time in 2022 when I was just beginning the full draft of The Mires and was/am just in awe. Talk about a novel about someone/s who have ‘gone through something’, that ‘makes us feel things more intensely’! If I had time, I’d read it once a year.

.

.

Damien: Oh yes, Middlemarch! Like Laurence, I also love Edith Wharton, and Henry James was huge for me. Then William Faulkner. Then Thomas Bernhard, Gerald Murnane, Penelope Fitzgerald. More recently (last twenty years!), I’ve been drawn to a certain wonkiness of prose style in writers such as Christina Stead, Elizabeth Bowen, Doris Lessing, Norman Rush, Joy Williams, Dermot Healy, where the sentences don’t end in the expected places. I think I was trying to move on from smoothness to a kind of ugly or awkward — not in subject matter but in the prose. But truly the greatest reading experience (separate from writing influence) of my life has been The Story of the Stone, the 18th-century Chinese novel by Cao Xueqin. Five volumes in the incredible translation by David Hawkes and John Minford. Better than Proust. When I went to China a few years ago, someone helped me buy a second-hand copy in Mandarin. My retirement will be learning the language so I can read that book. The novel is also known as Dream of the Red Chamber. And that is my dream. (The novel is full of characters who are deluded.)

Kirsty: It seems, a year after his death, I am still thinking about the powerful influence the work of Vincent O’Sullivan has been in my own education – academic, intellectual and imaginative. His scholarship and work on Mansfield lifted her, as a literary subject, right out of the bookshelf at home and the schoolrooms of my childhood in Wellington, and placed her bang-slap at the centre of literary Modernism in the English language. That was a game changer for me. That one could imagine a context of ‘home’ that was also ‘away’.

Mansfield had taught me that idea first – but it was O’Sullivan’s work that gave the whole thing ballast and authority and…heft! All his own literary work is an expansion of that same idea. His poetry and novels and stories. He brings both hemispheres together, wraps pasts into presents and futures, and shows us that the imagination can…roam!

Paula: Where are you all thinking about roaming, in any sense, in the near future?

Laurence: The area that means the most to me, where I roam on a daily basis, is Signal Hill above Dunedin. The more time I spend on the hill, moving slowly and looking at things the greater my appreciation for nature. At the moment there is a fly agaric that is pushing its way through the rock-hard, compacted clay on the edge of the track. The ground is as hard as concrete and it is a marvel that it can actually break through. It just fills me with wonder every time I see it.

At this time of year the lower bush is almost a cathedral of bird calls: bellbirds, tūī and fantails, and the sound enfolds me as I walk through the trees. Down on the playing fields each morning a large flock of black-backed gulls gather and feed on the grass and then -it’s quite incredible -they all rise up together and circle once or twice while calling out loudly. The noise is intense – I don’t understand how they have the energy to fly and clack-call so loudly, both at the same time. They disappear over the stadium and once they land they’re quiet again. In the evening they fly past my house, up North Valley to roost up on Upper Junction, near Mt. Cargill. It’s magic.

Tina: I love that sense of repetition, and watching a place over time, and close attention that your relationship with Signal Hill reveals, Laurence. That kind of relationship with walking around Paraparaumu Beach was at the heart of The Mires. It’s the last place I thought I’d write about, because I like to get away from my immediate life and my immediate surrounds imaginatively when writing, but when I read Elif Shafak’s incredible evocation of Istanbul in 10 Minutes and 38 Seconds in this Strange World, I wondered if I could write something anywhere near as vivid about my own neighbourhood, which is not considered the best place to live on the Kāpiti Coast. Why not? In Aotearoa we live in these incredibly beautiful places and a lot of the time, we take it for granted. In general, I don’t think we take time to really look properly, so I love what you’re describing, Laurence.

If I’m lucky enough to go overseas for anything, I kind of use that as an opportunity to retrain my seeing. Wandering and wonder and curiosity are so key for a writer, so I spend as much of my time in other countries doing that if I can. Last year I went to Japan with the express purpose of seeking awe – Japan is such an extraordinary place for that for lots of reasons – the mixture of very ancient and very modern culture, the reverence for nature and for quietness. But when I come back, I’m always trying to bring my new eyes with me, to see my homeplaces the way someone else might see them if they’d never been here. In writing, my next project is short stories, which for me is kind of the literary equivalent of this wandering and wonder. It’s very freeing. I don’t have to know where I’m going or how I’m going to get there, although I do know that given the times we live in there may be a fair bit of dark humour and horror.

Damien: Paying attention is everything. The comedy of getting things wrong is also high on my list of pleasures from fiction. I’m going to talk about At the Grand Glacier Hotel again because that’s what I’m reading. The narrator’s yearning to know more and to connect more deeply with the natural world is such a strong thread and such a good source of the comedy and pathos of the novel. She makes these difficult, tentative forays outside the hotel and has thoughts: What is that bird singing to me? And: I won’t admit that I can’t remember its Māori name. Our longing for meaningfulness is so close to ridiculousness.

But then, because Laurence’s narrator is recovering from the surgery on her leg and is disabled, she must also study again everything she thought she knew, such as how to get out of the bath. The scrambling of our usual coordinates is a great prompt for fear and uncertainty and hence story. If our old habits don’t work, what’s the new narrative? I think that’s how fiction can be sneakily political without leaving the bathroom. Our subject matter doesn’t need the obviously public to get at issues of significance. It drives me nuts when this writing is referred to as ‘quiet’. When Laurence’s narrator, dreading all kinds of humiliation, ends up crawling over the sides of the bath and then is pressed face down on the floor, this is not ‘quiet’.

I’m really not sure what’s next for me, fiction-wise. I’m finishing a set of songs which I’ll release later in the year. It’s really good to be involved in music since the words aren’t doing all the work! I can stop saying all these things and just let the guitar or the keyboards take over.

Kirsty: I love how everyone has that place of nourishment and return…And, as Tina says, these kinds of environments – places where we look and re-look and learn to look, and remember – are vital, and not only for writers. Everyone desires that special point of reference; it’s part of what makes us human. And these locations, contexts, geographies – they work upon our imagination to comfort us and bring replenishment and joy…A kind of homecoming.

For me, the special places have a kind of overlay, a sort of doubling – they make of my here a there, and vice versa; they ease the past into the present and back again. Because I no longer live in New Zealand, New Zealand remains a powerfully present landscape to me. There’s not a day goes by when I’m in London or the Highlands of Scotland where I also live and am not flooded with that sense of homecoming; the feeling that really, I am in New Zealand and that the world of my childhood has never left me, that it’s all around. So I’m not in Sutherland or West London, at all, then, but that the other beloved place is the only here and now. And the New Zealand of my infinite return and replenishment is Wellington and the Wairarapa, each overlaying my experience of cities and the countryside respectively.

So, say, I look up from my desk in Sutherland and see a landscape of low hills and paddocks, a big sky and a view that stretches on into a green faded by the sun and wind – and I am straight back to my past: long holidays with my grandmother, and aunt and cousins on their farm. Or I’m walking past a cafe somewhere, and there: I’m really in Wellington. Doesn’t matter where I actually am; as far as I’m concerned I’m in Thorndon, for sure. I remember once when I’d asked Bill Manhire to give a reading to some of my students at Dundee, and afterwards, we were walking around that city and I said to him, ‘See? Doesn’t Dundee make you think of Wellington too? The same layout, combination of hills and water? The same kind of streets? Don’t you think it’s exactly the same feel and mood?’ Bill gave me a funny look and said: ‘I think you’ve been here a long time, Kirsty …’ But truly, this stuff for me is real. It’s the stuff of my imagination and my experience, both, and it’s powerful and exciting and real. ………………………Alfredton in the North Wairarapa. Image supplied by Kirsty Gunn.

………………………Alfredton in the North Wairarapa. Image supplied by Kirsty Gunn.

'NZ literature is such a vast and varied thing' - Pip Adam