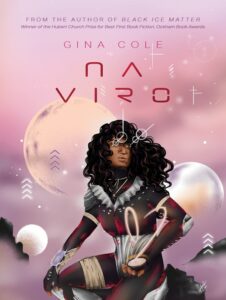

‘The spaceship of our ancestors’

Gina Cole on writing Pasifikafuturism and discovering a ‘galaxy of islands’

.

I have always been a science fiction nerd, largely due to the steady diet of Hollywood science fiction programmes I grew up watching on television in the 1970s: Star Trek, Time Tunnel, Land of the Giants, I Dream of Jeannie, Get Smart, Dr Who. Some of these productions have been rebooted or updated for new audiences, which speaks to the enduring appeal of the genre. I have loved science fiction ever since.

However, what those Hollywood productions had in common was a lack of representation of any people of colour – except for one show, Star Trek. Star Trek was influential for me because of Nichelle Nichols, who played Lieutenant Uhura. Lieutenant Uhura – a Swahili name – was a communications officer on the starship Enterprise, and she was in constant dialogue with Captain Kirk. It wasn’t unusual for me to see a black woman and a white man in conversation because my mother is Fijian and my father is Pākehā. But Lieutenant Uhura was the only black woman on television or anywhere else in cultural production in 1970s Aotearoa that I was aware of as a young person.

There were also very few science fiction novels written by Pacific writers. This remains the case today. I wanted that to change. So when I enrolled to do a PhD in creative writing at Massey University, I decided to write about science fiction and specifically science fiction set in space, featuring Pacific characters and Pacific culture, for a Pasifika readership and anyone else interested in science fiction written from a Pacific Ocean point of view. This is what I call Pasifikafuturism.

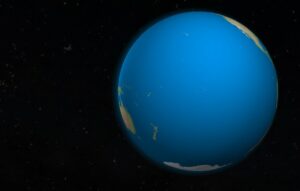

The Pacific Ocean is a vast body of water covering one-third of the Earth’s surface. Sometimes it’s called the blue continent, the biggest continent on Earth.

Digital rendering of the satellite view of the Pacific Ocean. Sourced from Globalquiz.org. Image credit: Przemek Pietrak.

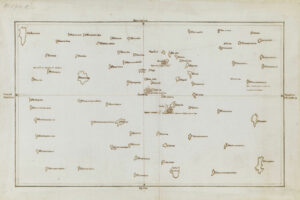

The colonial view of the Pacific was that of ‘islands in a far-flung sea’, a perspective which suggests smallness and isolation, helplessness and solitude. From an Indigenous perspective, as Tongan academic Epeli Hau’ofa wrote in an influential 1993 essay, it is ‘a sea of islands’. This suggests a vast expansive region and a sense of connection. Indigenous Pacific peoples share an interconnected web of relationships and cultures through our common geographic location in the Pacific. The title of Hau’ofa’s selected works, published in 2008, is We Are the Ocean. The sea is our highway, a fluid biotic mass that connects us.

Chart showing the Pacific Islands, based on information provided by Tupaia. Attributed to James Cook, circa 1769-70 © British Library.

Although Indigenous Pacific peoples do not have a pan-Pacific identity we do share many cultural practices, including an ancestral culture of waka building and a navigational culture of ‘wayfinding’ or celestial navigation. The waka is an Indigenous Pacific technology shaped by the Pacific Ocean environment, and a container of cultural knowledge, equalling any Western model of physics. Waka builder and master navigator Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr defines wayfinding as ‘the ability to travel across thousands of miles of ocean safely and efficiently, using nothing but the ancestral knowledge of the past and the clues provided by nature to find land far below the distant horizon’.1

Wayfinding requires a navigator to sit in the ‘eternal present’2, taking stock of the natural environment around them to navigate to their destination. Wayfinding techniques are cultural knowledge that come from connection and relationship with the environment that enabled my ancestors to navigate across huge Pacific Ocean expanses hundreds of years ago.

The waka is a symbol of the common origins and common ancestry of Pacific people. Writer Herb Kane calls the waka ‘the spaceship of our ancestors, because with it, they made explorations that were, in the context of their culture, just as staggering as our effort to go to the moon and other planets today.’ 3 The ancient knowledge of waka building and wayfinding navigation was nearly lost due to the incursions of the colonial project into Pacific culture.

But these cultural practices have endured. In 1976 Hokule’a, a double-hulled ocean-going waka, sailed from Hawaii to Tahiti and back following customary ocean pathways without the aid of modern instrumentation. Barclay-Kerr notes that Hokule’a’s inaugural voyage marked ‘the first step in the reawakening of a dying Pacific practise.’4

Hokule’a arriving in Honolulu from Tahiti in 1976 . Image sourced from Wikipedia

This brings me to the Pacific concept of the ‘vā’. Samoan writer Albert Wendt defines the vā as the ‘space between, the betweenness, not empty space that separates, but space that relates, that holds separate entities and things together in the Unity-that-is All, the space that is context, giving meaning to things.’5 Accordingly, vā can denote the space between two people or two islands or two planets. In Pasifika culture it is not empty space. It is a space of connection, and it needs to be nurtured and cared for.

The re-emergence of our ancestral practice of wayfinding navigation is a present-day expression of the persistence, strength and evolution of Indigenous Pacific culture.

Pasifika cultural practices like this and waka building, together with the Pasifika perspective of the vast Pacific Ocean as a ‘sea of islands’, and the concept of the vā or the space between, underpin my formulation of Pasifikafuturism.

In writing my novel Na Viro, a work I describe as Pasifikafuturist fiction, I take these cultural practices and principles up into space – into ‘a sky of islands’ or a ‘galaxy of islands’ or even a ‘universe of islands’. Interstellar space is a future setting for our Pacific cultural practice of wayfinding navigation, a way of travelling through space, and a model for leadership. I seek to subvert colonial conceptions of Indigenous Pacific culture in both form and content, to enact Indigenous knowledge and to re-enlist an Indigenous Pacific imagining of the future through story.

The writing and publication of Pasifikafuturism was a way for me to explore anti-colonial mindscapes which embody the spirit of struggle and survival for Indigenous peoples in the Pacific. The novel’s title, Na Viro, is Fijian for ‘whirlpool’. It’s a science fiction fantasy about a young Fijian Tongan Majuran woman named Tia Grom-Eddy who leaves her home on Namu Island in the Pacific to join a spaceship captained by her mother, Dani. Tia travels into space to rescue her sister from a whirlpool. A central narrative thread running through the novel is the metaphorical idea that there is an ocean in space and a galaxy in the ocean. The Pasifika science of wayfinding navigation can be transferred from an oceanic setting to a cosmic one as a means of navigating both realms: both are connected in the vā.

The term Pasifikafuturism was inspired by my research into Afrofuturism, which includes science fiction written by African American writers, and Indigenous Futurism which includes science fiction written by First Nations peoples in North America. I say ‘includes’ because these are cultural movements that bridge all the arts – not just literature but also design, fashion, dance, fine art and music. The Routledge Handbook of CoFuturisms6 describes these as representations of possible futures arising from non-Western cultures and ethnic histories that disrupt the ‘imperial gaze’.

Similarly, Pasifikafuturism recognises – in artistic form – a Pacific Ocean point of view on technology, creative ideas about the future, and science fiction. This viewpoint provides a tool kit to recover Indigenous histories that may have been lost in the colonial project and to create counter futures. It is anchored in our relationship with the Pacific Ocean and our cultural practices. Our ancestors used the sun the moon, the stars and signs in the Pacific Ocean environment – as well as waves, currents, clouds, winds and birds – to navigate across the sea. Wayfinding provides a methodology for envisioning the future in imaginative, transformative and positive expressions of Pacific peoples in science fiction.

Footnotes:

1 Barclay-Kerr, Hoturoa. ‘From Myth and Legend to Reality: Voyages of Rediscovery and Knowledge’. Global South Ethnographies, edited by Elke emerald et al., Sense, 2016.

2 P.24, Spiller, Chellie et al. Wayfinding Leadership: Ground-Breaking Wisdom for Developing Leaders. Huia, 2015.

3 Kane, Herb. ‘Wayfinders a Pacific Odyssey: Ask the Expert Herb Kane.’ www.pbs.org/wayfinders/ask_kane.html.

4 Ibid

5 Refiti, Albert. ‘Making Spaces: Polynesian Architecture in Aotearoa New Zealand’. The Pacific Dimension of Contemporary New Zealand Arts, edited by Sean Mallon and Pandora Fulimano Pererira, Te Papa Press, 2002.

6 Edited By Taryne Jade Taylor, Isiah Lavender III, Grace L. Dillon, Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, Routledge 2024

Feature header image: Fijian drua SEMA MAKAWA, a double-hulled war canoe. Courtesy of the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa, 1993.367.1

'I felt energised by the freedom of 'making things up’' - Maxine Alterio