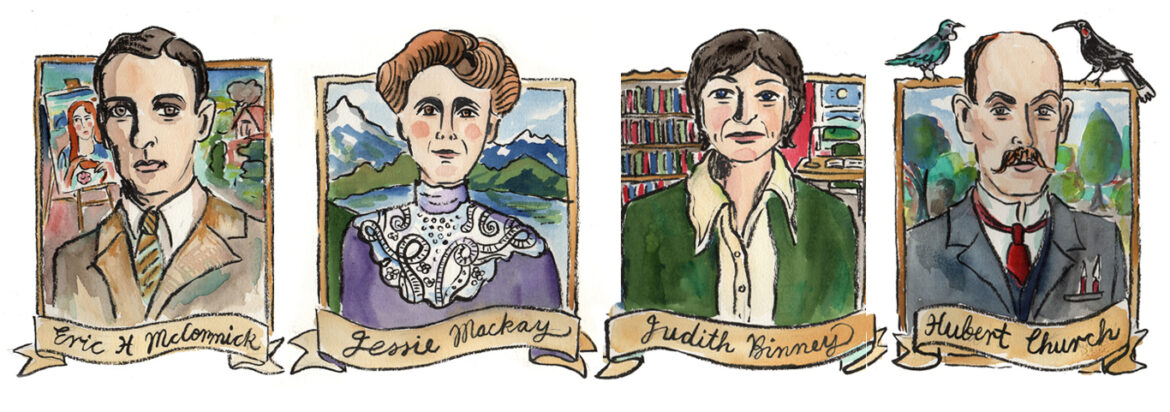

Illustrations by Sarah Laing.

Best First Books

The prizes for best first book in New Zealand have a storied history. PEN founded the poetry award in 1940 as a tribute to Jessie Mackay (1864–1938) – a poet, journalist and political activist, described by Alan Mulgan as a ‘crusader all her life’. James K. Baxter won the award in 1958 for In Fires of No Return: the prize money was £50, which he described as ‘a welcome gift for a man with a family’.

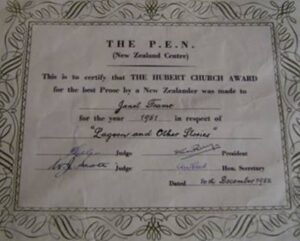

The fiction prize was established in 1945 thanks to a bequest from the widow of Hubert Church (1857–1932), an Australian poet and novelist who spent much of his working life in New Zealand. Janet Frame famously won this award in 1951 for The Lagoon and Other Stories: the news reached her in Seacliff Hospital near Dunedin, where she was on the waiting list for a lobotomy – a surgery that was cancelled when the hospital’s superintendent learned about the award.

The prizes for best first book have persisted, in recent years rolled into our national book awards. There are now four prizes, embracing the additional categories of General Non-Fiction and Illustrated Non-Fiction. This year they’re supported by the Mātātuhi Foundation, and the prize money for each award increases to $3000.

The longlists for the 2023 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, announced in early February, include fourteen first-time authors – an increase from the ten debuts longlisted in 2022. The category shortlists will be announced on 8 March and the winners – including the four Best First Book Awards recipients – will be announced at a public ceremony on 17 May during the Auckland Writers Festival.

The Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry longlist of ten includes five debuts: Meat Lovers by Rebecca Hawkes; People Person by Joanna Cho; Sedition by Anahera Maire Gildea; Surrender by Michaela Keeble; and We’re All Made of Lightning by Khadro Mohamed.

Contenders for the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction – valued this year at $64,000 – include two debut books by Māori writers: the story collection Home Theatre by Anthony Lapwood and the novel How to Loiter in a Turf War by Coco Solid.

The two debuts in the Booksellers Aotearoa New Zealand Award for Illustrated Non-Fiction are I am Autistic by Chanelle Moriah and Kai: Food Stories and Recipes from my Family Table by Christall Lowe.

In the General Non-Fiction category, there are five ‘first’ books: Gaylene’s Take: Her Life in New Zealand Film by Gaylene Preston; the bestselling memoir Grand: Becoming my Mother’s Daughter by Noelle McCarthy; Lāuga: Understanding Samoan Oratory by Sadat Muaiava; The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi by Ned Fletcher; and The Road to Gondwana: In Search of the Lost Supercontinent by Bill Morris.

A number of our ANZL Fellows and Members are past winners of the Best First Book prizes, and we asked some of them to share stories about their first publications.

Witi Ihimaera: Pounamu, Pounamu

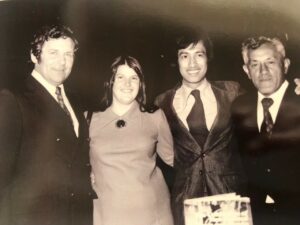

Publisher David Heap, Jane and Witi Ihimaera, and Witi’s father Tom at the Goodman Fiedler Wattie Book Awards, 1973

Like all things, it’s the context that’s as interesting as the event. And the context is that while there was a lot of support for Pounamu, Pounamu, there was also antagonism. For instance, a bunch of Māori academics didn’t like the book and called on my publishers to tell them so. I can’t substantiate this, however, as my then publishers had a fire in their warehouse sometime in the 1980s I think, and the records were destroyed so you’re just going to have to trust me on this.

Not only that but some of the early reviews were racist and gratuitous, referring to my work as, for instance, folk art, sentimental and either a) too Māori or b) not Māori enough. Another of the issues was that I had applied for a grant to write Pounamu Pounamu (and Tangi and Whānau) from what was then called the Literature Fund but failed, so you’ll excuse me for thinking that there were still gatekeepers of the canon around at the time.

All of this adds up to what I call atmospherics. And they can often colour the decisions of those who judge awards, all the backstage opinions about what is worthy and what isn’t, has the writer paid his/her dues and so on. But I was lucky that I had a publisher, David Heap, who put Pounamu, Pounamu forward to the Wattie Awards (1973, where it placed third) and then it was awarded the NZSA/Hubert Church prize for Best First Book.

Therefore, I think if I was to characterise how I felt, it was not to pat myself on the head but to give the book the heads up: I pai koe, you done good. And then to tell it to go out into the world and do its mahi.

There wasn’t a celebratory event as I recall and I can’t remember if any money came attached to it – maybe $120 or something like that, but the money didn’t matter. What mattered was that NZSA was known at the time as PEN New Zealand and associated internationally as well as nationally for excellence in writing. I felt I was being recognised internationally. I guess it was one of those bits and pieces of magic that writers like to weave around themselves to encourage a better sense of self-worth as they enter the starting gate.

One of the ironies is that I won the award fifty years ago. Now, fifty years later I am the NZSA’s honorary president. How the heck did that happen? My sense of it is that the early awards I managed to obtain put me not only on a pathway as a writer but also on the ara to represent Māori and indigenous writing. To open the gateways so as to ensure that the diversity I was honoured for would continue to transform literature in Aotearoa.

Patricia Grace: Waiariki

In 1975, as a newly published, first-time writer I knew very little about awards for writers. I know I would have been surprised and delighted to receive the award for ‘Best first book’. I think there was a monetary prize. I don’t remember there being a ceremony.

However, the abiding memory I have of that time is the sense of pride I felt in knowing that Waiariki had been judged and chosen by Janet Frame. This both endorsed and encouraged me as a writer at a time when I was considering whether or not writing was something I would pursue.

Some years later, in an event in Janet Frame’s honour at Wellington Town Hall, I was able to thank her.

Alan Duff: Once Were Warriors

Normally, I’d consider it self-indulgent navel-gazing to be bothered writing about my first published book. I mean, so what? But the first? I remember it like yesterday.

Living in total obscurity in Waipukurau, Central Hawke’s Bay, and several kilometres out from the township in a Pukeora Hospital house where my wife, Joanna, was the general manager, I was anxiously awaiting the publisher’s decision that seemed to take forever coming.

Then the phone in the passageway went. Only landlines back in 1990. It was the publisher with the news: ‘We are going to publish your book’. I have no memory of what was said after that. Only that I put the phone down and leaned against the wall and cried my eyes out. As you would with a life history like mine.

I was player/coach of a local senior rugby team, with the attitude of tough guys don’t cry. Now, here I am bawling like a baby? ‘Over a book?’ I could hear my non-reader rugby mates saying, seeing their faces in one collective expression of incomprehension. As I’d not breathed a word of my literary aspirations, as you don’t in the rugby culture. Not back then.

A couple months before, when I finished the last of eleven or twelves drafts at five AM, I went for a one-hour run and felt like I was floating. Got back home, woke my wife and told her – for some reason – ‘I just made history’. Don’t ask me why I made such an arrogant, confident statement. It’s just what came out. I even wrote some weeks later to the Prime Minister, David Lange, asking, ‘How would the country’s most eloquent man like to launch the career of New Zealand’s…’ Better not say the rest, you can fill in the dots.

My ecstasy turned to something less when the husband-and-wife publishers (soon to become my friends) offered me a $500 advance which I flatly turned down. I was putting sweat equity into building our own home in Havelock North, travelling every morning and back late evening. I needed a few thousand to pay for the concrete floor slab pour. They agreed a $3000 advance.

God knows what gave me what I singularly lacked, the self-confidence to both invite the P.M. to launch my career, as well risk not being published if they wouldn’t up my advance. For years and years, I had bored everyone witless with my promise that ‘one day…’

Well, when the day came, I can say it bettered even that wild dream of mine. To get the first advance copy and stare at it over and over in total disbelief. That’s my name on the front cover? Once Were Warriors by…? Can’t be.

Now, here I am in the thirty third year since I was published, a lot of books and two movie adaptations later, another dream fulfilled of putting books into the homes of disadvantaged children just gone past the 15 million mark. And happily breaking my rule not to boast.

Catherine Chidgey: In a Fishbone Church

My first novel, In a Fishbone Church, was launched at Writers and Readers Week in Wellington in March 1998, and won the NZSA Hubert Church Award for Best First Book at the Montana New Zealand Book Awards in July that year. It was also runner-up for the Deutz Medal, back when we still had runners-up; Maurice Gee won that year. Maurice had come to talk to my writing workshop at Victoria when I was working on Fishbone (he wrote longhand in exercise books, he told us, and on the right-hand page only, reserving the left for editing), so it seemed a bit unreal to be rubbing shoulders with him on the shortlist.

I remember standing among the crowd at the Auckland Town Hall, waiting for the announcement. I wore a long gold dress and velvet jacket, both made by my mother. Sales agent Neil Brown showed his support by sporting a fabulous fish-skeleton earring like the design on the cover of my book.

The dinner afterwards was a lively affair. There was a dance floor, and actual dancing; I remember my publisher busting several increasingly vigorous moves while sloshing red wine from the bottle down his white shirt. I also remember chatting with the gorgeous Margaret Mahy, who had been making the most of the refreshments and was rather wobbly by that stage of the evening. I tried to catch her arm when it was clear she was about to topple over, but she plonked herself down on her AW Reed Lifetime Achievement Award instead. Spectacular.

It was thrilling to win Best First Book, and it gave my fledgling career a huge boost; it helped to drum up attention overseas, and I imagine it paved the way for the novel to win Best First Book at the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize (South East Asia and South Pacific) the following year. In a Fishbone Church was based partly on my mother’s life, and I know how proud she was of the book’s success. She kept it beside her bed, and often read sections of it over the years, even as she entered dementia. When she died last year I found the bookmark showing the shortlisted titles marking her page in her copy, and the programme for the Awards tucked away with her precious mementoes.

I spent some of the prize money from the Montanas on a huge 1930s oak desk. It’s come from house to house with me and is so big that you have to take the legs off to shift it. I’ve written all my novels at it, and it still reminds me of that early exhilarating time.

Paula Morris: Queen of Beauty

I wrote my first novel for Bill Manhire and the MA at Victoria: we moved from New York to Wellington so I could take his course. By the time Queen of Beauty was published by Penguin in 2002, we were back in the U.S. and I was attending the Iowa Writers’ Workshop as the Glenn Schaeffer Fellow. (Those were the days). In October I came home for the book launch, which was held on the top floor of the Chapman Tripp law firm: one of my sister’s friends was a partner there. One guest thought my father was the security guard, because he was tall and Māori.

The following year I must have skipped classes for a few weeks, because I came back again, this time for the Montana New Zealand Book Awards. In those days the event moved around each year, following the Booksellers NZ convention. There was a big dinner in Christchurch, maybe at the stadium. All I remember about my Hubert Church speech is that I thanked independent book shops for supporting Queen of Beauty. Steve Braunias was there, in a three-piece suit: he worked at the Listener then, and the previous year had won the NZSA E.H. McCormick First Book Award for Non-Fiction, for Fool’s Paradise. Every time he left his table to smoke outside, people around me conjectured that he was storming out of the room. They seemed disappointed every time he returned.

Whatever the prize money was, I desperately needed it: for the two years we lived in Iowa, we were broke. My sister gave me some money, and that’s probably how I could afford to come home for the awards. In my second year at the Writers’ Workshop I met another New Zealander: she had reviewed Queen of Beauty for the Listener, under a pseudonym. She seemed to think my parents were divorced, and that my father taught at a university. I had to explain that my parents were still married and my father was a printer. I guess she assumed the novel was autobiographical. I never told her that I knew she was the reviewer.

After my MFA, we moved to New Orleans so I could teach at Tulane University. Although I’d visited New Orleans before (for PhD research; we also got married there), I hadn’t lived there when I wrote Queen of Beauty. If I could write the book again, there would be a lot more about heat and rain and flying cockroaches.

Kelly Ana Morey: Bloom

The ‘best first book’ component of the New Zealand Book Awards has always been an important stepping-stone in a new writer’s career. Not only is it a validation of your talent from your newly acquired peers, but it gives the all-important funding panels – those people who hand out money which buys you time to write – something tangible to hang an affirmative decision on. I genuinely cringe whenever I hear a new writer say they don’t care about prizes. You should care.

If I had one piece of advice to emerging writers it would be you only get one chance at the Best First Book Prize, so make it count. It could change your life.

When I wrote Bloom, my first novel, you bet I had an eye on the prize. I actually had very little published prior to Bloom’s publication by Penguin in 2003, so was largely a complete unknown. But I knew how things rolled in the world of literature, and understood that writerly survival, particularly as a urban Māori writer, was dependent on hitting key milestones – one of which was the NZSA Hubert Church prize.

Winning the prize got me booked for writers’ festivals, saw me receiving sometimes generous funding and has perhaps been something of a justification for the constant support I’ve had from publishers over the years. It doesn’t promise a free ride though. I’ve had more than my fair share of rejection. Twenty years, eight books and quite a few short lists along, I’m about to start my second writers’ residency, after approximately 30 residency applications over the years. There are people out there who haven’t published a book who have had more writers’ residencies than me so that just goes to prove how tough it can be even if you do hit those big milestones, make bestsellers lists and keep yourself fairly visible.

It would have been undoubtably even more difficult if Bloom hadn’t essentially made my career, which was in no small part due to it being the recipient of the 2004 Herbert Church Award for First Fiction.

Pip Adam: Everything We Hoped For

This is how I remember it: in 2011 I got an email from Helen Heath – then the publicist at VUP – asking me to come to a morning tea. I was quite worried about this. My story collection had received universally bad reviews and I thought maybe there was going to be an awkward conversation about how publishing me had been a mistake, and that could I take these boxes which contained the rest of my books and perhaps dispose of them.

So, I wasn’t looking forward to the morning tea but I summoned my courage and went up to the offices and everyone was there. I think at that stage it was Helen, me, Fergus Barrowman, Craig Gamble, Kyleigh Hodgson and Ashleigh Young. And there was cake which made me think, ‘Man, this must be harder for them than it is for me.’ Then I noticed everyone was happy; there was happy conversation and I thought, ‘Oh maybe we are here to celebrate Helen’s book,’ because I knew she’d just submitted it.

After a minute Helen, I think, said, ‘Do you know why you’re here?’ and I said, ‘No,’ and she said, ‘Well, you’ve won the Hubert Church Best First Book Award for Fiction,’ and I said, without missing a beat, ‘Oh. No. That’s Craig Cliff isn’t it?’ And then there was a lot of trying to explain to me what had happened and me saying, respectfully, I think you are all very, very wrong. I remember still not being fully convinced really until my name was up on the screen the night of the awards. Which was an amazing night. My friend Laurence Fearnley was up for best book of fiction and we had a fun night.

I remember a reviewer who had written a particularly harsh review coming up to me and talking to me about how his review hadn’t been negative and I was weird and ended up apologising to him. The thing I remember the most is that Fergus and I went up on stage together, and I remember feeling this overwhelming gratitude to him and VUP for taking a chance on my weird book.

I was writing another book by this time and I can still remember returning to that for the first time after the awards and feeling this new buoyancy around it, like there was space for me to write the way I felt like I needed to. The money was amazing. I was working part-time and doing my PhD I think and I remember the money really helped us have a couple of months of not worrying about where money would come from for bills.

Chris Tse: How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes

Although mine was the only first book on the poetry shortlist in 2016, no one had officially told me before the ceremony that I would be receiving the Best First Book award! Maybe I could’ve assumed it was happening, but there’s always the risk of getting excited and then letting yourself down. (Also, there was an instance a few years earlier when a debut book on the shortlist didn’t win Best First Book.) I guess this uncertainty meant that the question mark was hanging over me right up until the point they announced it, which made the whole experience of going to the book awards even more exciting.

At the ceremony I wore a blazer with feather epaulettes – my homage to Björk’s Oscar swan dress – which got its fair share of attention. People still bring it up to this day when I meet them, which is lovely, but it did set a very high bar for me for future outfits!

The first book awards are special – after all, everyone only ever gets one shot at them so in some ways there’s even more pressure and competition around them than the main categories. Validation is a funny beast and, as many have noted, awards only mean something to the people who win them. This award did indeed mean a lot to me – at the time it was the biggest moment in my writing career, capping off almost a decade since I wrote the first poems for How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes. The book has continued to live a storied life. I’m not sure whether this can be attributed to the award, though I’m sure it helped.

Gina Cole: Black Ice Matter

Gina Cole accepts her award from Maggie Barry at the 2017 Ockham NZ Book Awards, held in the Aotea Centre in Auckland.

I wrote Black Ice Matter during my MCW year at Auckland University in 2013. Selina Tusitala Marsh was my supervisor. As this was my first book I had no idea whether it was any good but I really enjoyed the entire process over the year of the MCW and working with Selina. As a new writer the whole eco-system of publishing and awards was a mystery to me. I was incredibly happy when Huia agreed to publish the book.

I was shocked when it won Best First Book at the Ockham NZ Book Awards in 2017. Receiving this prize was a huge endorsement and acknowledgement of me as a writer. It meant so much to me at the time. It really gave me the confidence to quit being a lawyer and to embark on a PhD in creative writing, and to pursue writing full time.

On the night of the Ockhams ceremony I wore my map suit with the Pacific Ocean on my right thigh. Brian Morris and Pania Tahau-Hodges from Huia came with me to the ceremony. The night itself is a bit of a blur. I hadn’t prepared a speech. I remember mumbling my thanks to everyone I could think of who had helped me and mooching off stage as fast as possible. My friends and family were very proud of me. I remember having to do a whole round of media which I was not prepared for at all.

I received $2,500 in prize money, and spent some of it attending the 2017 Lexicon Science Fiction Fantasy Convention in Taupo. The rest of it went on paying bills.

'NZ literature is such a vast and varied thing' - Pip Adam