From the edge of the sky

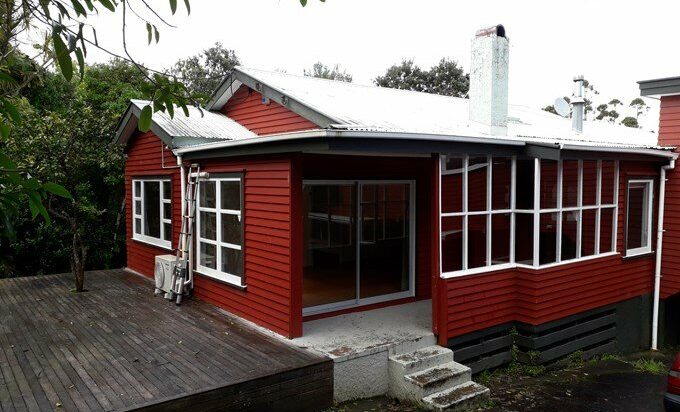

Number 35 Arapito Road, Titirangi, West Auckland is now a listed Category 1 Historic Place. The Going West Trust plan to restore the house and open it as a writers’ residency. But if you asked any writer under the age of 40 why this is, I doubt if any would come up with the right answer. This presents an object lesson in why some dead authors are remembered and others not only forgotten but consciously blanked.

The modest, undistinguished property below the road was the home of Maurice Shadbolt from 1964 to 2000. During the second half of the 20th century, Shadbolt was a constant, ubiquitous presence in our literary world. He published 15 novels and short story collections, ten non-fiction books, a seminal play. He won the Wattie Book of the Year award twice, was published regularly in the US and UK and his work was heavily translated. He even had a story published in the New Yorker before Janet Frame. So why have Shadbolt’s work and opinions been studiously ignored since his death 20 years ago?

In the context of the current debate and furore surrounding the Treaty Principles bill and Māori-Pākehā relations, it might be useful to look at what he wrote that is relevant, at least in order to help understand where we once were and what may be of remaining value in understanding who we are now.

Born in 1932, Shadbolt grew up in Te Kuiti in relatively poor circumstances during the Depression and war decades. Many school mates and neighbours were Māori, and he attended events at Te Kooti’s meeting house. This early experience, of communities and landscapes, strongly influenced his writing throughout his life. The short story that the New Yorker chose to publish from his first collection The New Zealanders in 1959 was ‘The Strangers’ which revealed the conflicting attitude towards life and work between a Pākehā farmer and his Māori employee. ‘There were the two of them, neither understanding the other, and I stood between, only knowing that of all the strange and terrible things in life the strangest and most terrible was that of two people not understanding each other.’ The ‘I’ of the young boy between was Shadbolt the author who repeatedly wrote between the two worlds in the belief they could and should come together, even that they were together.

The activating incident of his first novel, Among the Cinders (1965), is the death of Sam Waikai from a fall when his Pākehā mate young Nick startles him on finding ancient bones in a cave. Shadbolt later wrote that he and his Te Kuiti school mates explored caves that were everywhere in the Waitomo landscape. ‘Some were rumoured to be ancient burial places heaped with old Maori bones.’ His childhood was ‘never short on rumour, terror, and death in sorry form.’ He avoided some caves after learning of the ‘violent consequence of violating tapu … Your hair went white overnight; your teeth fell out; you went mad and were dead in a week.’ A sense of superstition and the power of the supernatural were enduring.

Although Māori characters continued to be included in much of Shadbolt’s fiction, they did not become central until his major trilogy of novels located in the New Zealand Wars, beginning with Season of the Jew in 1986. It told the story of Te Kooti’s ‘rebel’ Poverty Bay campaigns of the late 1860s, following his escape with Ringatu followers from Chatham Island banishment, and concluding with the scandalous execution of Hamiora Pere for treason, pour encourager les autres. Shadbolt’s sympathy with Māori and their charismatic leaders during the wars was original for a Pākehā novelist, partly stimulated by the awakening to Māori perspectives of the period expressed in contemporary historical narratives by historians like James Belich. Season of the Jew’s best-selling importance was marked by Shadbolt gaining his second Wattie Award in 1987.

In his trilogy, Shadbolt used Pākehā soldiers for his entry into the warrior world of the Māori. But where George Fairweather in Season of the Jew was fictional, Kimball Bent of Monday’s Warriors (1990) was a real, deserting soldier who, as a captive, assisted Titokowaru in his campaigns against Pākehā settlers in south Taranaki. In Monday’s Warriors, and the other novels of the trilogy, Shadbolt based his stories on the historical record and acknowledged the research of Belich and the value of ‘walking the ground’ of battle sites with military historian Christopher Pugsley. The sense of authenticity is strongest in Monday’s Warriors, and weakest in the third novel The House of Strife (1993), which was set in the 1840s wars in the north.

Season of the Jew ends with an imagined late-life reconciliation between Te Kooti and his Pākehā adversary, soldier-painter George Fairweather, a figurative gesture of mutual forgiveness between enemies, between cultures, that Shadbolt idealised. Despite this, and his long friendships with Māori creatives like artist Selwyn Muru and master carver Pine Taiapa – whom he claimed as a key inspiration in his own artistic development – Shadbolt became disenchanted with the rise of Māori activism and the trends towards separatism. The beliefs and structures that had underpinned most of Shadbolt’s work, and especially the Wars Trilogy, seemed under threat from a once-homogenous society that was steadily factionalising with the growth of what became known as ‘identity politics’.

His anger erupted in a damning review of the 1991 collection of contributed essays, edited by Michael King, Pakeha: The Quest for Identity in New Zealand. Shadbolt wrote that the book was for the ‘chattering class’ in the ‘Peter Pan land of the politically correct: all things Maori good, all things European bad. No one questions the concept of “Maori culture” or suggests that it may be a much-thinned, post-Christian version of the real thing, about as authentic as the Scottish kilt.’ He rejected the term Pākehā as of no use in an increasingly multi-cultural country and that the use of the word ‘argues that white New Zealanders exist only in relation to Maori.’ His review, in fact, focussed on only one of the essays in the book but it struck a nerve, generating much correspondence in the columns of the New Zealand Herald, both for and against.

Shadbolt’s strong feelings arose not only from his friendships with and support of Māori from childhood, but also from his own sense of belonging, of his family being rooted in the land. His criticism had been reinforced by his concurrent exploration of Shadbolt family origins in New Zealand, beginning in 1859, which resulted in his much-reprinted memoir One of Ben’s (1993). In the 1991 debate, he declared he was no Pākehā. ‘I’m a New Zealander thank you, a pale-skinned Polynesian. New Zealanders are my iwi, Titirangi is my turangawaewae.’

Shadbolt’s declared identity went back almost 30 years to his text for that eulogy to New Zealand, Gift of the Sea, powerfully illustrated by Brian Brake’s photographs. It was a celebration of what the country had achieved by the early 1960s, its pioneering heroes, its Māori heritage, its future as a country of mixed-race Polynesians. It sold close on 100,000 copies, reassuring the dominant culture that all was well. Shadbolt projected this image overseas with his books and international magazine articles; more than any other writer of his time, he took New Zealand to the world. His belief in the image of New Zealand he promoted resulted in what was probably his best novel, The Lovelock Version (1980). It was a complete mythical reimagining of New Zealand history that historian W.H. Oliver described as a ‘comic epic with serious social purpose.’ It was a ‘lament for the loss of a better possibility than the option in fact chosen.’

How much of Shadbolt’s sense of being a New Zealander survives now, especially following the political and cultural changes pushing towards Māori sovereignty since his death 20 years ago? Is his vision a wreck on a forgotten shore? When I returned to New Zealand in 2014 after a research trip to the UK, a customs officer at Auckland airport, as he was going through my hand luggage, asked me what I did for a living. ‘I’m a writer,’ I said, expecting a quizzical look that suggested, ‘Tell me another one.’ But he asked, ‘So what are you writing?’ After I said that I was researching for a biography of Maurice Shadbolt, I waited for a frown and a shake of the head.

Instead he said, ‘Well I think One of Ben’s is the best New Zealand book ever written.’ I nodded and smiled and said, ‘Oh, right,’ although I did not agree. I was taken aback but his response seemed to indicate the lingering influence of Shadbolt’s novels and non-fiction books, so many of them best-sellers, on the psyche of Pākehā New Zealanders, and of how they thought about themselves and their country. Shadbolt thought of himself as much tangata whenua as Māori. Perhaps many Pākehā believe the same.

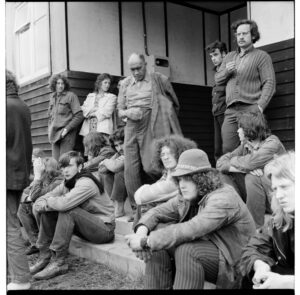

James K. Baxter’s funeral, Hiruharama (Jerusalem), Whanganui, in October 1972; Maurice Shadbolt standing on the far right. Photo credit: Ans Westra, 1936–2023. Used with permission of Suite Tirohanga.

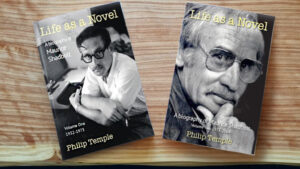

Shadbolt’s insistence on himself as tangata whenua may be one reason why his work has been largely ignored since his death. Perhaps the rise of identity politics around ethnicity and gender mean that younger New Zealanders are not interested in 20th century images of New Zealand history and identity from a dead white male, especially one with a reputation as a notorious philanderer. This further complicated his legacy during the first years of the #MeToo movement. The first volume of my biography of Shadbolt, Life As a Novel, was published in 2018 to excellent reviews, but I was not invited to take part in any literary festival (save in my home town), even to Going West.

This raises the chronic, thorny question of how much knowledge of authors’ private lives should influence a reader’s approach to their work. In recent times, there has been a tendency to reframe appreciation of an author’s work through the lens of extra-literary judgments. Life and work are intertwined but Shadbolt was essentially a storyteller, and his writing is best approached without moral complication. Perhaps when 35 Arapito Road, with its bush studio, finally becomes the location for an inspiring writers’ residency, Maurice Shadbolt’s stories and myths, created from ‘the edge of the sky’, will be better understood and appreciated.

Philip Temple is the author of the two-volume Life as Novel: a biography of Maurice Shadbolt.

‘Inspiration is the name for a privileged kind of listening’ - David Howard