Messages from God

Philip Temple on the books he read in 2022

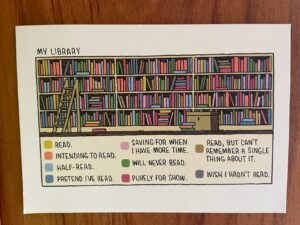

It must be December, because Paula Morris asked, What have you read this year? Can I even remember? And did I really read that, when the book’s actually still sitting there, pressing my guilt button? Attached to the side of the first book-case in our library is this postcard from The Snooty Bookshop Fifty Literary Postcards by Tom Gauld, just to keep us honest. We have books in our library which fit every category except, surely not, Purely for Show.’

I get through 40-odd books a year, other than books consulted for research. These may be new books, recent books that have been waiting patiently, books remembered and re-read, or books that should have been read long ago. From all those, not so many remain clearly in the mind, ones that have registered with lingering import and enlightenment and, sometimes, joy.

First, the fiction. The most intriguing local work for me has been Vincent O’Sullivan’s Mary’s Boy, Jean-Jacques. The title work, a novella, is a marvellous imagining of what happened to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein’s creature after he was abandoned in the Arctic. Here he is picked up by a passing ship and transported to Fiordland where he escapes into the bush, joining a fellow disfigured creature. It is a moving and intriguing parable for all outsiders rejected by humanity and centres a classic story in our own history. Mary’s Boy, Jean-Jacques deserves to be published separately in a small format, illustrated hardback edition but I doubt if the publisher has the equal imagination for that.

Richard Powers’ Overstory deservedly won a Pulitzer Prize for its fictionalised account of protestors who tried to save the great redwood forests, and the Canadian woman who first posited that forest trees supported each other in communal ecosystems. She was derided by male colleagues but eventually proved right. But it didn’t help the redwoods much. Good ideas and inspiration here for all those fighting to save our native forests.

Oh, those Irish fiction writers! I found Colm Toibin’s The Magician (about Thomas Mann) disappointing after his The Master (Henry James). But Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is a masterpiece. It could refer to the length of what is strictly a novella and can be read within a couple of hours (I couldn’t help myself). But Keegan has produced something mighty, a work of such sympathy and sensibility around the people and 1980s social climate of New Ross and the convent on the hill with its laundry girls that one is brought to both tears and joy. It also rates as a Christmas story of such power to become a 21st century A Christmas Carol.

Diane [Brown] went down to the Regent Book Sale (one book in, one book out, she lies) and came back with William Trevor’s The Story of Lucy Gault, knowing how much I admire Trevor’s work. It was shortlisted for the Booker (like Keegan’s novella) all of twenty years ago but I had somehow missed it. This takes a bit longer to read but is equally difficult to put down. Set a hundred years ago on the coast somewhere near Cork, it tells of a family forced to leave their estate under threat of house-burning rebels during the turbulent establishment of the Irish Republic, and of how a young girl becomes separated from her parents. To say more would be too much of a spoiler but the novel covers thirty years of change to a small town and rural community through the story of a house and its inhabitants. I once kissed the Blarney Stone near Cork but, alas, it did not produce for me the effortless lyricism of Trevor’s prose.

Biography: I found Patricia Grace’s From the Centre: A Writer’s Life humbling. Her unassuming and calm narrative reveals a life led by someone who has always known who she is and what matters, whose values have remained true and rewarding for everyone around her. And from that calm at the centre of the busyness and demands of whānau and community she has produced some of our finest literature. Tū, for example, remains our best war novel.

Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret by Craig Brown. Yes, I know. But book club members assured me this was something different. Brown says he played a kind of ‘Where’s Wally? Or a super-snobby version of I-Spy’. He trolled through every account of Princess Margaret, public and private, to produce a different kind of biography that presents hall of mirrors views of someone who, one reviewer thought, displayed ‘utter rottenness’ of character (but blames it on her Mum). Yet Picasso wanted to marry her as did Jeremy Thorpe, along with many others among the line-up of vile supporting characters. I cringed, was appalled, laughed out loud—and was fascinated. After the Coronation in 1953, a friend said to Margaret that she looked really sad and she replied, ‘I lost a father and now I’ve lost a sister.’ So, in the end, I even felt a little bit sorry for her, too.

Faber & Faber, The Untold Story by Toby Faber is a great writer’s read, telling the story of the most enduring London publishing house just knocking on its centenary door. T.S. Eliot (with his second wife Valerie) dominates but the book reveals his fallible judgments. He turned down Orwell’s Animal Farm (and consequently 1984) while William Golding’s first novel only made it through when a member of the secretarial staff suggested a good title for it would be Lord of the Flies.

The Bush by Don Watson is a no-holds-barred, and deeply informed, account of the destructive clearance of the Australian ‘bush’ by someone who grew up on an outback farm. A heart-breaking account of what has happened to the natural world across the Ditch. Unsurprisingly, it won the New South Wales Premier Book of the Year Award.

Over the past few years, I have been reading, researching and writing about our two Big Issues— massive resource depletion beyond Limits to Growth with its spawn, Climate Change; and Treaty of Waitangi matters and co-governance. This year I have read He Kupu Taurangi by Chris Finlayson and James Christmas, which covers Treaty settlements and cases of co-governance; and historical accounts and analysis in the form of The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi by Ned Fletcher (which I’ve reviewed for Reading Room) and Vincent O’Malley’s The Great War for New Zealand.

Discussion with others led me back to 2002’s Histories Power and Loss edited by Andrew Sharp and Paul McHugh. Its essays on ‘uses of the past’ by such luminaries as W.H. Oliver, Te Maire Tau and Judith Binney remind me that there has been much informed and wise commentary lost sight of amid current polarising arguments. Lyndsay Head’s ‘The pursuit of modernity in Māori society’, in particular, tells us that the current narrative around the attitudes of Rangatira towards British settlement needs a more rigorous and balanced examination.

By Christmas I expect to finish time-travelling with Bryan Walpert’s intriguing novel Entanglement and David Grant’s more plodding journey through the chronology of Anderton. For sheer pleasure and doses of wisdom I dip into 100 Poems: Seamus Heaney, selected by his family. The Faber & Faber biography reveals that when T.S. Eliot wrote to say he accepted his first book of poems, Heaney said: ‘It was like a message from God.’ Some of Heaney’s poems come across just like that.

P.S. Did I say we had nothing in our library ‘Purely for show’? Er … gathering dust in the corner is the large-format Timechart of Biblical History with old and elaborate images illustrating Bible stories. Another refugee from the Regent Book Sale, I think, and definitely messages from God.

'I started to feel very guilty, as though I’d perpetrated a crime, a rort' - Stephanie Johnson