‘What did I miss?’ Ten years of the Ockhams

The Ockham New Zealand Book Awards celebrates its tenth anniversary. Paula Morris takes notes and makes disclosures.

Last year at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, the Prime Minister took some flak from some writers and audience members – including fiction finalist Pip Adam, who read a pointed defence of Te Tiriti. To avoid a repeat this year, the Hon. Paul Goldsmith, Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage (historian and biographer of John Banks and Don Brash, among others), made a short speech and then a swift exit through the stage door, before any awards were handed out.

He was probably home long before Damien Wilkins – winner of the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction for his novel Delirious – managed to run onto the stage. It was almost 9 PM; host Miriama Kamo asked Nigel Gavin’s on-stage band to fill time after the fiction announcement, checking her phone to tell us Wilkins was hurtling his way from Auckland airport. Air New Zealand was the unexpected villain of the day: mechanical issues with an early-afternoon plane stranded Wilkins in Wellington airport for five hours and kept poetry sponsors Mary and Peter Biggs from flying up at all. (Wilkins’ wife, slumming it on Jetstar, arrived in plenty of time.) ‘What did I miss?’ Wilkins joked.

Some big hints, as people noted during the event’s after-party. All the non-awards speeches – including one by Ockham Residential founder Mark Todd, usually an event closer – were moved up to the start of the ceremony, possibly to buy time for the $65,000 winner. During the fiction category citation, Thom Conroy, the judging convenor, paused to ask if Wilkins had arrived yet. He hadn’t: his publisher and longtime friend Fergus Barrowman, of Te Herenga Waka University Press, did the reading on Wilkins’ behalf and accepted the award – a bright turquoise acorn – for him as well. ‘I’m still not Damien,’ he said, adding that Delirious was his favourite of all Wilkins’ novels.

Wilkins, who gave a thoughtful and generous speech, was a popular and deserving winner. ‘Delirious has a lot of what you’d expect from Wilkins,’ wrote Laura Borrowdale on the Aotearoa NZ Review of Books. ‘It’s a novel that’s about “something”, that has intellectual meat on its plot bones, beautiful writing, and a very, very New Zealand setting.’

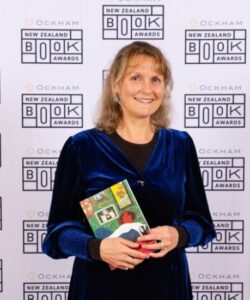

This was the tenth anniversary of the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, celebrated with a pacey ceremony, an expert host, and explosions of gold streamers at the end. It was also the 57th anniversary of our national book awards in one of its many previous incarnations. Paul Goldsmith noted that the first novel to ever win at these awards – not including best first book – was Smith’s Dream by C. K. Stead, in 1972. ‘He’s still here,’ said Goldsmith, and indeed he was, looking rakish in his striped scarf, a poetry finalist for his collection In the Half Light of a Dying Day. Aged 92, Stead is also the oldest-ever finalist in these national book awards, but this year the poetry prize went to the youngest of the four finalists, Emma Neale (born in 1969), for her superb collection Liar, Liar, Lick, Split.

In Wilkins’ speech, he joked that when he last won at these awards – in 1994, for his debut novel, The Miserables – all of New Zealand literature could fit in a small room, on a few pieces of furniture, their names on a one-page list. Times have changed. The number of submissions for the Ockhams this year sounded like a record: 55 books in General Nonfiction, 53 in Fiction, 37 in Poetry and 30 in the most glamorous (and expensive) category, Illustrated Nonfiction. The finalists in each category climbed onto the stage to read short excerpts from their books. In most categories, this meant four people. In Illustrated Nonfiction it was ten, (almost) all the writers and editors who created the four contending books. (Illustrated Nonfiction finalists also get a slide show.)

Neither of the nonfiction awards were a surprise, despite the strength of competition in both categories. Toi te Mana: An Indigenous History of Māori Art (Auckland University Press) by Māori art historians Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) and Ngarino Ellis (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou) – (disclosure 1: they are my colleagues at University of Auckland). The book is so heavy – 600 pages! – the authors had to offload it onto publisher Sam Elworthy before sharing the podium for their acceptance speech. It’s ‘an outstanding contribution to Māori culture, arts and creativity,’ writes Maia Nuku (Ngāi Tai), Oceanic Arts curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Category convenor Chris Szekely described it as a book ‘of enduring significance’, begun 14 years ago by the late Jonathan Mane-Wheoki (Ngāpuhi, Te Aupōuri, Ngāti Kurī).

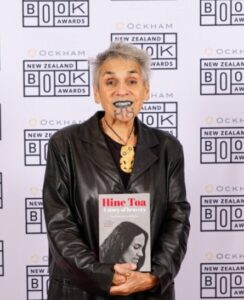

The General Nonfiction winner was Ngāhuia te Awekōtuku for her stunning coming-of-age memoir Hine Toa – ‘an important book,’ I wrote in a review published on the ANZRB and in shortened form in the Listener, describing it as ‘vital to write, vital to publish and vital to read’. Ngāhuia gave an eloquent speech, though she was trembling and said she was ‘feeling rather shattered’; her partner celebrated the win in the aisle with a haka.

At the end of her memoir, Ngāhuia asks: ‘What became of the revolution?’ Perhaps because of the absence of Prime Ministers at this year’s event, writers with a turn at the microphone said less about our own society and political issues, though nonfiction finalist Una Cruikshank – in her speech after winning best first book – gave a shout-out to her ‘anarchist friends in the audience and ended with ‘Free Palestine!’ Badges seemed the preferred protest mode: Te Tiriti, Palestine, the Rainbow flag. I asked poetry judge, the always-eclectic David Eggleton, about his badge. ‘It’s the old five-cent coin,’ he told me. (There’s a poem called ‘The Five Cent Coin’ in his 2009 collection Time of the icebergs.)

Most finalists wore black, though possibly without symbolism. Cruikshank wore black lace gloves but a bright dress (with panniers) that included Day-of-the-Dead skulls. Lawrence Fearnley, a fiction finalist, wore mountain-climbing boots, as though she had just stepped from the pages of her own novel. Robert Sullivan, a poetry finalist, held a Māori mouth flute he’s learning to play ‘like a cigar’, he said, in tribute to his smoker father. Emma Neale apologised that her speech was ‘a shitty first draft’. Mark Todd, in his sponsor’s speech, apologised because his most recent read was not local. It was East of Eden by John Steinbeck. (‘Fuck, it’s good.)

Last night the four Best First Book winners were announced: these awards include the oldest in New Zealand: the Jessie Mackay Prize for Poetry, first awarded in 1941, and the Hubert Church Prize for Fiction, established in 1945. They are now sponsored by the Mātatuhi Foundation (disclosure 2: I’m a trustee and also a past winner of the Hubert Church); the prize includes membership of the New Zealand Society of the Authors, a tribute to the NZSA’s important role in establishing both the Mackay and Church awards (disclosure 3: I’m a longtime NZSA member and former President of Honour). The NZSA included an insert on the history of these prizes in the Ockhams programme: the QR code, which we’ll add to the ANZL site, leads readers to a complete list of winners back to the 1940s.

The winners this year include two first books that were finalists in the main nonfiction categories: Sight Lines: Women and Art in Aotearoa and Una Cruickshank’s The Chthonic Cycle. The fiction winner was Michelle Rahurahu (Ngāti Rahurahu, Ngāti Tahu–Ngāti Whaoa) for her debut novel Rahurahu; the poetry winner was Manuali’I by Rex Letoa Paget. All the best-first-book winners were published by university or small independent presses. In fact, only one of the night’s eight winners, across all categories, was published by a multinational trade publisher – Hine Toa, published by HarperCollins NZ. This isn’t a surprise for a category like poetry, but with the other categories could reflect the increasingly commercial exigencies of the multinationals based here.

Penguin Random House used to be a major publisher of New Zealand fiction: will that continue with its reduced staff and local list? Only one Penguin fiction title made this year’s longlist: Fearnley’s At the Grand Glacier Hotel, also a finalist. Newcomer Moa Press, part of Hachette NZ, had two books on the fiction longlist: Shilo Kina’s All That We Know and Saraid de Silva’s debut novel Amma (disclosure 4: I run the Master of Creative Writing programme where de Silva wrote the first draft of this novel.)

Usually the Ockham NZ Book Awards are followed by social media complaints that memoirs and essays are overlooked in favour of Serious History, and that the General Nonfiction category should be split to ensure more space for creative nonfiction. In fact, six of the ten nonfiction winners in the Ockhams era have been creative nonfiction. This year none of the finalists were ‘straight’ history; the main award was for a memoir and the best first book was for an essay collection.

So let me raise a different issue for a different category. Saraid de Silva was the only Asian NZ writer on the fiction longlist. Overlooked this year were The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat by past finalist Brannavan Gnanalingam and when I open the shop, the imaginative debut novel from Romesh Dissanayake. Last year’s fiction longlist included one Asian NZ novel, Emma Ling Sidnam’s debut Backwaters (disclosure 5: Alison Wong and I included work by de Silva, Dissanayake and Sidnam in our anthology A Clear Dawn: New Asian Voices from Aotearoa New Zealand.) Like de Silva, Sidnam was a contender for best first book (fiction) but did not win. The only Asian fiction writer to win at our national book awards remains my co-editor Alison Wong, for As the Earth Turns Silver in 2010.

As Damien Wilkins says, New Zealand literature has changed since 1992; it keeps changing, and growing more expansive and diverse. New stories, fresh voices, different audiences. Our national book prize judges began recognising Asian NZ poets in 2016 when Chris Tse won the Jessie Mackay Prize for his debut How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes. Chinese Fish by Grace Yee won the Peter and Mary Biggs Award for Poetry in 2024. Joanna Cho was a poetry finalist in 2023, Nina Mingya Powles in 2021. The absences in fiction prizes begin to look egregious.

From left to right: Damien Wilkins (Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction), Ngāhuia te Awekōtuku (General Nonfiction), Emma Neale (Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry), Ngarino Ellis and Deidre Brown (BookHub Award for Illustrated Nonfiction). Photo credit: LK Creative.

'Character to some extent is much a construction of the reader as it is of the writer.' - Lloyd Jones