Photo credit: Kevin Rabalais.

‘I became obsessed’

ANZL writers on what they’ve been reading in 2024 – new books, classics, books for research, books for pleasure, books from Aotearoa NZ or around the world.

* * *

Tina Shaw

Tina’s recent book A House Built on Sand (Text Publishing, 2024) was the winner of the 2023 Michael Gifkins Prize.

.

In my Book Discussion Scheme book group, 2024 accidentally turned into the year of the memoir. The one I liked best was Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour. It contained many elements that were great to discuss, such as a guy’s obsession with his absent, eccentric father; becoming a father oneself; and the journey of taking care of a rescue magpie named Benzene. It is a story about an ‘interspecies family set-up’ that weaves human and magpie beings into a larger metaphor to do with real life.

.

In my other book group, we take turns to choose a book each month to read. One book I chose was Carl Nixon’s The Waters (and why wasn’t this novel shortlisted for the Ockhams?), about the Waters family – practical, athletic Mark; beautiful Davey; and the baby of the family, Samantha – who have had to face more than their fair share of challenges. Described as ‘a novel in 21 stories’, Carl riffs on family dynamics with a deft touch.

Another book I introduced to the group was The Deck by Fiona Farrell (honestly, why wasn’t this amazing novel not even longlisted for the Ockhams?). A group hunker down at a modern coastal retreat and share stories. There are images from this novel that have stayed with me: the girl lying under a plum tree who connects with a young deer. The mysterious yacht anchored in the bay below the house.

Judging the YA category of the Storylines Notable Book Awards, I was impressed with Migration by Steph Matuku, a story about friendship, featuring a school for training fighters, strategic thinkers and military personnel.

Other reading … To inform the novel I’m currently writing, I’ve been reading Resistance by Australian author Jacinta Halloran. I love the conversations that take place in this novel and how the characters are defined by what they say – or don’t say. It’s about a family therapist who is talking to a family who took off into the outback. It’s subtle, empathetic, political.

Not Australian, but somehow connected in my mind to Resistance are the works of Rachel Cusk (author of the Outline trilogy). This year, Parade was released. It isn’t my favourite Cusk work, but it’s still very interesting. As the Guardian put it (better than I could): ‘it pursues and deepens her lifelong interest in the relationship between art and life in a narrative sequence that also explores fraught alliances between men and women, the nature of gender and the complications involved in losing a parent.’

I kept thinking: This would never have been published in New Zealand!

There have been random discoveries: Western Lane by Chatna Maroo, a coming-of-age story about girls playing competitive squash, and fathers; and Boulder by Eva Baltasar (translated by Julia Sanches) about a woman nicknamed ‘Boulder’ by her lover. Working as a cook on merchant ships, she becomes obsessively connected with a Swedish woman, giving up freedom to take up life on land, like ordinary folk. What is so compelling about this short novel is its strong and poetic language, described as ‘prose as brittle and beautiful as an ancient saga’.

My latest find is All Fours by Miranda July. OMG. I have to take this one to my book group: it’ll shake them up! Put in simple terms, a 45-year-old artist and perimenopausal woman sets off on a road trip but ends up only 30 minutes from home at a nondescript motel where she discovers a beautiful boy who comes to obsess her and remakes her motel room into five-star luxury. Trying to deal with her obsession, she has a kind of sexual awakening. It’s a story about ageing and one woman’s quest for a new kind of freedom. Totally engrossing; a crazy ride.

.

To end on a non-fiction note (a genre I don’t read much, unless it’s for research): The Crewe Murders: Inside New Zealand’s most infamous cold case by James Hollings and Kirsty Johnstone. Fascinating stuff.

.

.

Brannavan Gnanalingam

Brannavan’s latest work The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat (Lawrence & Gibson, 2024) is available now.

.

I am very structured with my reading, and essentially have three categories of reading. The first, is when I’m reading for pleasure, and read whatever I feel like. For me, this is the period when I’m between books, a kind of ‘fallow ground’ period. The second period, is when I’m reading around the idea of the book I’m planning to work on, when I’m getting myself ready to write and am building the clear sense of what the book is about e.g. if I’m writing a horror novel, like Slow Down, You’re Here, I’m reading a lot of horror. The third is when I read to get around problems I might be having when I’m writing, and I read to work things out.

This year was dominated for me by the writing of The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat, the idea of which, came to me at the start of the year. The book is a parody of the political bio, a form that forced me to think how ‘events’ could be structured in my book, and how I’d need to downplay momentum and focus more on episodic storytelling. I read memoirs / autobiographies of politicians from all sides of the spectrum, including Rodney Hide (My Year of Living Dangerously), Helen Clark (Helen Clark: Inside Stories by Claudia Pond Eyley and Dan Salmon), Jim Bolger (Fridays with Jim by David Cohen), and John Tamihere (Black and White). I noticed the caginess of most political bios, as politicians sought to protect their legacies, or at least not burn too many bridges. I found Simon Bridges’ National Identity the most interesting, as he was more thoughtful than most, and honest in his own failings but also some of the challenges he encountered.

I also read books relevant for the themes, such as Byron C Clark’s Fear, around the rise of the online far right in Aotearoa, along with a few famous novels about the interwar period and the immediately aftermath of the war including The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, Djiboutian writer Abdourahman A Waberi’s Harvest of Skulls (about Rwanda), All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren, Irmgard Keun’s After Midnight (a magnificent novel about the rise of 1930s fascism, that is both light and hilarious, while also deeply chilling in the way ordinary people can collude with fascism and scapegoating) and The Tin Drum by Gunter Grass (I was less enamoured by this one, although I suspect that that was due to the awkwardness around Grass’ own complicity with the Nazi regime).

This was unusual writing period for me, in that Kartik’s voice came out fairly clear and sustained. It meant I didn’t read all that much when I was working at quite a feverish pace. Accordingly, it also meant I didn’t have to read around any problems. One book that did stand out though was reading Huo Yan’s Dry Milk, which is a rare novel about Asian immigrants in which the protagonist is thoroughly dislikeable. Dry Milk taught me not to be worried about maintaining my tone / steely gaze on the utter failings of my protagonist (not that I needed much encouragement given the political figures who inspired my book), and one of the joys this year, has been discovering how much of an impact Dry Milk has had among Asian writers in both Aotearoa and Australia. It’s like a secret club.

I have enjoyed being able to read for pleasure though, since finishing my book. Local highlights include Saraid de Silva’s AMMA, which along with romesh dissanayake’s When I open the shop (which I had read as romesh’s MA supervisor) showcased two assured and brilliant Sri Lankan writers in this country, and I hope more people read their work. Tusiata Avia’s Big Fat Brown Bitch is Avia at both her most vulnerable and scabrous best, and Avia’s continued targeting by certain politicians is an ongoing scandal. Simone Kaho’s beautiful Heal! looks at the messiness of trauma while also emphasising defiance and survival and subversion in the aftermath. Stacey Teague’s Plastic pulls together the various strands of identity and how fraught making peace with it all can be. Talia Marshall’s Whaea Blue is one of the most ruthless self-eviscerations I’ve ever read, and her sentences force the reader to shake their complacency in ways few writers bother to do. JP Pomare’s Seventeen Years Later showcases Pomare’s complete mastery of narrative, while adding a political resonance to his excellent and underrated body of work. Jared Davidson’s Blood and Dirt tells the histories of how much of Aotearoa’s infrastructure (streets, ports, buildings) have been built by slave labour / prisoner labour, which we also managed to export to Samoa, Niue, and the Cook Islands – like the best histories, it forces you to see your country in a completely different light. Maddie Ballard’s Bound is a lovely and assured debut collection of essays, in which Ballard incorporates her love of sewing into examining ideas of identity, belonging and holding space for yourself in the world.

Global highlights include Michael Winkler’s brilliantly chaotic Grimmish, Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera’s The House of Hunger, Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani’s short stories (including in the collection Men in the Sun), David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives (the current political environment doesn’t feel all that removed from the horrors of the religious right / Republican response in the ’80s to AIDS, as brutally depicted by Wojnarowicz’s ruthless memoir).

.

I have a very large TBR pile, and I look forward to cracking into a bunch of the summer, including Tina Makereti’s The Mires, Lee Murray’s Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud, Cher Tan’s Peripathetic, David Coventry’s Performance, and Olive Nuttall’s Kitten.

.

Rachael King

Rachael’s latest work The Grimmelings (Allen & Unwin, 2024) is available now.

.

Quite a few people I’ve talked to lately have had a hard time reading this year. Keeping on top of the news cycle fractures my brain and makes it hard to concentrate on either reading or writing, so, like many, I haven’t read all the books I intended to, and I have veered away from ‘difficult’ books to more comforting reads. I also had a book published this year, which is a distraction in itself, and I have read more children’s books than adults’ because that is my writing community now, and I want to support the eco-system. Middlegrade books are having a moment in Aotearoa, with some strong and beautifully crafted books on offer for tweens and under (and over – these books are for everyone). There were ten novels on the recent Storylines Notable Books list, with only two on the Young Adult section. Two! Why this is warrants further investigation.

My notable mentions in children’s books are Claire Mabey’s The Raven’s Eye Runaways, a gorgeous debut from a beautiful writer; Jane Arthur’s poignant and poetic Brown Bird; another intelligent cli-fi from Bren MacDibble, The Apprentice Witnesser; Stacy Gregg’s Margaret Mahy Award winner, Nine Girls, which combines a quirky family story with a history lesson; and Tania Roxborogh’s exciting and topical Charlie Tangaroa and the God of War, the second in a planned trilogy. All these books would make excellent Christmas presents for young people in your life (and then steal them and read on a beach yourself).

I became obsessed with the British author Catherine Storr when I reread the frankly terrifying 1958 children’s novel Marianne Dreams in preparation for my Backlisted debut (if you haven’t found the best books podcast go and get it now). I also read Marianne Dreams’ lesser-known sequel Marianne & Mark, and fell in love with Thursday, a young adult novel that sets the Tam Lin myth in 1970 suburban London, and I have hunted down many more of her books to read next year.

A Backlisted recommendation led me to my favourite novel of the year, Joan Barfoot’s Gaining Ground (published by The Women’s Press in 1980), which is extremely hard to get, but good old Christchurch City Libraries have a well-worn copy to borrow. It made me want to cut off all my hair and move to an isolated cottage somewhere.

Also memorable was a newer book – I hesitate to call it a novel – Ben Tuffnell’s The North Shore, an eerie and singular work that starts out as folk horror, but transforms into a series of essays on art and nature and back again. One to read slowly and thoughtfully.

Two non-fiction books that I loved were Alan Garner’s sublime Powsels and Thrums, essays and reflections on creativity and his life, and Sam Leith’s brilliant The Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood Reading, which is accessible, humorous and fascinating. And big. I’m reviewing it for the Listener so I’ll leave it at that for now.

Finally, my list is haunted by the books I bought but didn’t read, so this summer I’m looking forward to Tina Makereti’s The Mires, Louise Wallace’s Ash, Mary-Anne Scott’s The Mess of Our Lives, and Gareth and Louise Ward’s The Bookshop Detectives: Dead Girl Gone.

.

Vanda Symon

Vanda’s latest work Prey (Orenda Books, 2024) is available now.

.

One of the fun reading challenges I gave myself this year was to read from around the world. I realised I was tending to read books from the English speaking world, so decided to expand my horizons and seek out translated books to read. It was such a great challenge that I am going to continue with it in 2025. My best pick of these was a bit of a cheat because French writer Fred Vargas was already a favourite author. I adore her Inspector Adamsberg books, and This Poison Will Remain did not disappoint. This case weaves in death by spider venom, dark local intrigue from the past, and the absolutely fascinating history of the recluses.

I read a lot of non-fiction and memoir and one of my favourites this year was Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder by Salman Rushdie. Rushdie was grievously injured in 2022 while about to deliver a lecture on the importance of keeping writers safe when he was attacked by a man wielding a knife. This memoir is stunning and gives such insight into his immense journey to recovery, and the power of love. It was a moving and an uplifting read.

I always have New Zealand fiction and non-fiction on the go and the book that was a surprise hit for me was the memoir The Bookseller at the End of the World by Ruth Shaw. What an amazing life she has lead, with adventure and heart-break. It made my life feel so tame! I will have to go visit her tiny bookshops in Manapouri now.

My favourite book of the year though was The Trials of Marjorie Crowe by C.S.Robertson. This novel beautifully ties together the modern day tendency to accuse and try by social media, and the terrible historic legacy of burning women who were different, of burning the witch. The titular character is odd, and complex and has no choice but to try and solve the murders she is accused of before they try to burn the witch.

Paula Morris

Paula’s new novel Yellow Palace is forthcoming in 2025.

.

One of my projects this year is editing the letters Robin Hyde sent back from Asia and Britain in 1938 and 1939, the last two years of her life. I’ve been reading a lot directly related to China and the Sino-Japanese War – James Bertram, Agnes Smedley, Edgar Snow. A recent book by Chris Elder, Interesting Times: Some New Zealanders in Republican China, was useful preparation for a research trip to China in November. I had foot surgery in August, so ended up – like Hyde – relying on a walking stick there, limping around Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Xuzhou, Qingdao and Shanghai.

.

As usual, I was also led down various garden paths by other books, including the glorious Bosshard in China: Documenting Social Change in the 1930s and the brief but bizarre The China Letter by Dr George Hill Hodel, who worked in a war-devastated Wuhan (Hankow) in 1946. Until the book arrived from the US, looking as though it was produced in someone’s garage, I didn’t realise that Hodel is more famous as an (alleged) serial killer in Los Angeles.

.

To get a stronger sense of Shanghai in the 30s I read the charming Remembering Shanghai: A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels by Isabel Sun Chao and her daughter Claire Chao, and of course became obsessed with the brilliance and style of Eileen Chang. The stories and novellas Love in a Fallen City are set in Hong Kong and Shanghai, ranging from the end of Imperial China through the Republican era to the fall of Hong Kong to the Japanese. A small bilingual book called Eileen Chang’s Shanghai by Chun Zi, Wang Zhendong and Feng Hong was an indispensable guide to the city where she was born – in 1920 – and became first a literary sensation, then a pariah.

For the novel I’m finishing work on, I read Africa is Not a Country: Notes on a Bright Continent by Dipo Faloyin, a book that is sharp, funny, informative and depressing, and An African History of Africa by Zeinab Badawi. (I also saw the fantastic documentary Dahomey, directed by Mati Diop, in this year’s International Film Festival.) Although I have never been interested in anything even vaguely scientific, I learned a lot from Nicolas Niarchos in essays like ‘The Dark Side of Congo’s Cobalt Rush’ in the New Yorker and ‘In Congo’s Cobalt Mines’ in the New York Review of Books.

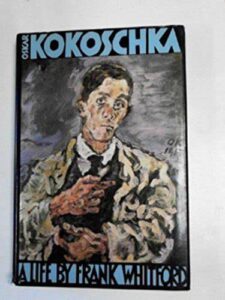

Also for the novel I dived one again into the insanity that was the relationship between Alma Mahler and Oskar Kokoschka. I keep taking Oskar Kokoschka: A Life by Frank Whitford out of Auckland Public Library to read about the life-size doll OK commissioned after Alma left him. He cavorted with it in public even though it was covered in a feathery swanskin and didn’t look much like Alma at all. Finally, at a party sometime in the 1920s, he cut off its head.

.

My novel is not about Kokoschka or Alma Mahler, or about mining in DRC, but these are things I needed to read.

'Many of our best stories profit from a meeting of New Zealand and overseas influences' - Owen Marshall