The 2023 finalists for the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the Ockham Awards night, from left to right: Monty Soutar, Michael Bennett, Cristina Sanders and Catherine Chidgey. Photo credit: Marcel Tromp.

Ockham NZ Book Awards 2023: Spreading the Wealth

Like the Auckland Writers Festival, the Ockham NZ Book Awards returned to the Aotea Centre this week, after last year’s excursion to the more intimate Q Theatre. Also back: musicians on the stage, Jack Tame at the MC podium, the big harakeke flower display, and some writers reading for longer than their allotted four minutes. Still, the awards show was pacy and the audience lively, and from the mihi by Tui Hawke and Blackie Tohiariki to a number of the shortlisted books and the majority of speeches – including from the Hon. Willow-Jean Prime, Associate Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage – the use of te reo Māori reminded us of where these awards take place and the unique culture they celebrate. The evening’s final speaker, Ockham Residential’s Mark Todd, called for a change next year: we should be saying the Ockham Aotearoa NZ Book Awards, he said, and the enthusiastic crowd seemed to agree.

There are four genre categories in the book awards, and the biggest and broadest of them all is the General Non-Fiction category. It’s depressing that although high-quality local nonfiction books are thriving in New Zealand, this award has had no sponsor for its $12,000 prize since 2020, when the Royal Society Te Apārangi withdrew its support. There are annual calls for the category to split – there were six nonfiction categories in the Montana NZ Book Awards days – but none of these are backed by sponsors willing to put money on the table. The greatest clamour these days is not for a return to sub-categories like ‘Reference and Anthology’ but for a separate category for memoirs and collections of personal essays, even though these books form one of the smallest groupings of entries within the category.

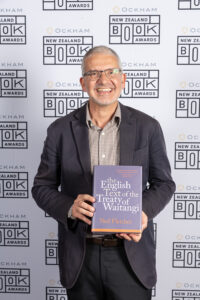

This year’s longlist and shortlist will do nothing to appease memoir-and-essay fans, especially as books by Fiona Kidman, Gaylene Preston and Kate Camp didn’t survive the longlist cull, and writers like Mohamed Hassan and Jan Kemp didn’t even make it that far. In their place was one memoir, Noelle McCarthy’s bestselling Grand (Penguin); an investigation into a hidden history, Paul Diamond’s Downfall: The Destruction of Charles Mackay (Massey University Press); a portrait of Northland tupuna, A Fire in the Belly of Hineāmaru by Melinda Webber and Te Kapua O’Connor (Auckland University Press); and the massive doorstop of landmark scholarship that is The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi by Ned Fletcher (Bridget Williams Books).

The judges in this category were columnist Anna Rawhiti-Connell, scholar Alison Jones, who has won this prize for her own memoir, and historian Te Maire Tau. Both Fletcher and McCarthy are debut writers, and the judges broke with tradition by awarding each a prize: Fletcher the main award, and McCarthy the E.H. McCormick Prize for best first book. When his name was called, Fletcher looked stunned, but the judges’ comments suggest why his book won: it ‘sheds new light’ on the Treaty’s implications ‘and contributes fresh thinking to what remains a very live conversation’.

Ned Fletcher with Best First Book The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi. Photo credit: Marcel Tromp.

The decision to spread the wealth with the popular McCarthy suggests this year’s judges were skittish after the howls of outrage last year when Charlotte Grimshaw didn’t win this category with her memoir The Mirror Book. The winner then was Vincent O’Malley’s Voices from the New Zealand Wars / He Reo nō ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa, which means this is the second year in a row that Bridget Williams Books has published the nonfiction winner.

Though controversies over the poetry list won’t excite most in the New Zealand media, this was an unusual year for the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry, judged by three poets – Diane Brown, Serie Barford and Gregory Kan. Five of the eight longlisted books were debut collections. Missing from the list entirely were Elizabeth Smither and Robert Sullivan, both of whom had new books in 2022, and when the four finalists were announced, the well-reviewed and more established longlisted names – Janet Charman, Chris Tse – were gone. Still standing were, essentially, four emerging poets.

Two are debut writers: Khadro Mohamed and Joanna Cho, the latter dressed for the event in a vivid blue hanbok and a pair of white gomusin shoes. Anahera Gildea’s shortlisted collection was her first full-length poetry collection; Alice Te Punga Somerville is the author of a scholarly book and a long-form essay, but her shortlisted collection was her first book of poetry. That book, Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised (Auckland University Press), won the award, collected by her nephew Matiu on Te Punga Somerville’s behalf: she now lives in Canada. ‘Always Italicise shines for its finely crafted, poetically fluent and witty explorations of racism, colonisation, class, language and relationships,’ said the judges.

Alice Te Punga Somerville’s nephew Matiu and her mother with Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised. Photo credit: Marcel Tromp.

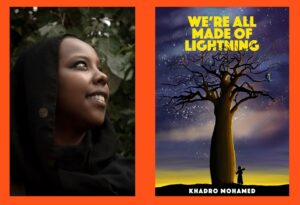

Khadro Mohamed, winner of the Jessie McKay Best First Book of Poetry award, was also out of the country last night, missing the awards. Her collection We’re All Made of Lightning was published by Tender Press, formerly known as We Are Babies Press. This is the second year in a row they’ve published the poetry debut of the year: last year’s winner was Nicole Titihuia Hawkins and her book Whai. (In other name-related news, Tender Press is distributed by the smartly named Expensive Hobby.)

Twenty-five-year-old Mohamed is the first African New Zealander to ever win the Jessie McKay – a prize first awarded in 1945. Both Mohamed and Cho are diasporic writers; Mohamed was born in Somalia and Cho in South Korea. Gildea and Te Punga Somerville are both Māori writers and both attached to universities: Gildea is a PhD student at Te Waka Herenga (Victoria University of Wellington), and Te Punga Somerville is a professor at the University of British Columbia. Incredibly, she is the first Māori writer to win the main poetry award since Hone Tuwhare in 2002, and in the past two decades only four Māori poets have won the best first book award: Hawkins, Tayi Tibble, Marty Smith and Kay McKenzie Cooke..

The Booksellers Aotearoa New Zealand Award for Illustrated Non-Fiction is typically a hard category to call, with so many strong contenders. It was surprising that Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art edited by Nigel Borell (Penguin Random House New Zealand / Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki) didn’t make the shortlist; surprising, too, perhaps, that Robin White: Something is Happening Here, edited by Sarah Farrar, Jill Trevelyan and Nina Tonga (Te Papa Press / Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki), didn’t win the category.

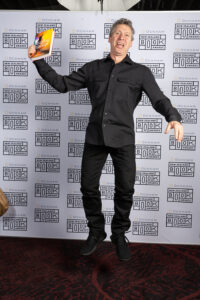

Nick Bollinger with Jumping Sundays: The Rise and Fall of the Counterculture in Aotearoa New Zealand. Photo credit: Marcel Tromp.

The judging panel this year was historian Jared Davidson, curator Anna-Marie White, and TV producer Taualeo’o Stephen Stehlin, and both the awards they handed out leaned in a more populist direction. The appealing Jumping Sundays: The Rise and Fall of the Counterculture in Aotearoa New Zealand by Nick Bollinger (Auckland University Press) won the main prize. ‘The cover alone is one of the best of the year,’ said the judges’ citation, describing the book ‘a fantastic example of scholarship, creativity and craft’. In his speech Bollinger thanked some of photographers featured in the book, including John Miller, Max Oettli and Ans Westra. A very surprised by Christall Lowe, author of Kai: Food Stories and Recipes from my Family Table (Bateman Books) – the ‘Edmonds cookbook for our time’ – won the Judith Binney Prize for best first book.

Christall Lowe with her winning book Kai: Food Stories and Recipes from my Family Table. Photo credit Marcel Tromp.

The final award of the evening was fiction, with its massive $64,000 prize. The reason for the large sum is there in the name – the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction. Jann Medlicott MNZM was a retired radiologist, philanthropist and avid reader of New Zealand fiction, and the money she endowed was intended to support and promote fiction specifically. Last May, she was on stage at the Q Theatre to present the ‘acorn’ in person. She died three months later.

Every year there’s grumbling about lack of equity between the awards and their prize money, and suggestions that the Medlicott funds be spread across all four categories, but this is not possible: the donation had clear terms, and the money she left can’t be shared or re-directed. Our book awards need more generous donors like Medlicott, with a passion for books and writers.

This year’s judges were novelist and past winner Stephanie Johnson, editor John Huria and bookseller Gemma Morrison, and they drew up a longlist with some surprise inclusions – like the dystopian fantasy Chevalier & Gawayn: The Ballad of the Dreamer by the late Phillip Mann (Quentin Wilson Publishing) – and disappointing exclusions, like Colleen Maria Lenihan’s debut story collection Kōhine (Huia) and Ruth Bayley’s outstanding World War II novel Barefoot (Eden Street Press). The finalists’ list was even more controversial, with past winners Lloyd Jones and Vincent O’Sullivan out, and three ‘genre’ novels rubbing shoulders with another past winner, Catherine Chidgey.

Two of these outliers were historical novels: the bestselling Kāwai: For Such a Time as This (Bateman), a first venture into fiction by historian Monty Soutar; and Mrs Jewell and the Wreck of the General Grant (Cuba Press) by Cristina Sanders, based on the true story of a nineteenth-century maritime disaster and the young woman who managed to survive. A crime novel by screenwriter Michael Bennett, Better the Blood (Simon & Schuster), was the most surprising inclusion of all: novels about detectives on the trail of a serial killer may shine at the Ngaio Marsh Awards but usually not at the Ockhams or its various past iterations. (All four writers discussed their novels in a round table published here earlier this month.)

Catherine Chidgey’s acclaimed The Axeman’s Carnival (Te Herenga Waka University Press) was the popular winner of this year’s prize: she previously won in 2017 for The Wish Child, so now has a second lurid acorn to add to her collection. Winner of the Hubert Church Award for best first book of fiction was Anthony Lapwood for his ‘unfailingly inventive’ debut story collection Home Theatre, also published by Te Herenga Waka University Press. Like Soutar and Bennett, Lapwood is a Māori writer, the third in four years to win the Hubert Church – following Rebecca K. Reilly in 2022 and Becky Manawatu in 2020. He’s also the first male Māori writer to win any kind of fiction award since Alan Duff in 1997, for What Becomes of the Broken Hearted?

That three Māori men were longlisted in the fiction category this year is a big deal, overlooked by most media. Is this just an unusual year or a hint of a new wave forming? What’s needed, still, is fiction for adults written in te reo, not simply translated. The Mūrau o te Tuhi / Māori Language Award awaits its first fiction recipient. It’ll happen, hopefully sooner rather than later. In 2014 every single winner at the Book Awards was a Pākehā writer apart from debut poet Marty Smith. Times change, and so do our publishers, our books and our awards.

Tom Moody is an American writer and editor living in Auckland.

'My readers turn up...and I meet them as human beings, not sales statistics on a royalty statement.' Fleur Adcock