‘What makes a winning essay?’

Emma Neale on Landfall’s Strong Words #3 and thinking aloud about New Zealand culture.

The Landfall essay competition has achieved its silver anniversary. In fact, it has bettered that: it turns twenty-six this year. Perhaps we can call 2023 the contest’s ‘art anniversary’. When marking a marriage of this duration, gift guides suggest any presents swapped should have a link to original art. (A Saskia Leek, Nick Austin, Sharon Singer or Star Gossage painting?) An art anniversary seems a suitable time to write an encomium of the award, especially given Landfall’s own constant championing of the visual arts, alongside its celebration of literary innovation and excellence.

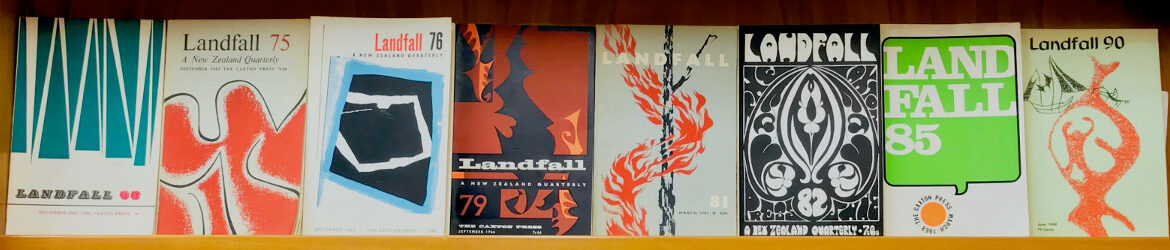

Initiated by Chris Price, the first woman editor of Landfall, the essay contest began in 1997, when it was launched as a way to mark the journal’s fiftieth year. Since 2009, the competition has been an annual award. As the Otago University Press website says:

The purpose of the competition remains as it was at the outset: to encourage New Zealand writers to think aloud about New Zealand culture, and to revive and sustain the tradition of vivid, contentious and creative essay writing in this country – as embodied in the non-fiction of early Landfall contributors such as Bill Pearson, in the essays of past winners of this competition, and in the essays the journal continues to publish.

Each year the competition, which can bring in entries on everything from birdsong to an analysis of body dysmorphia, is judged by the Landfall editor. All entries are anonymous, and the winner (announced and published in each November issue of Landfall) receives $3000 and a year’s subscription to Landfall, Aotearoa’s oldest literary print journal. Past winners include Tze Ming Mok, Peter Wells, Tracey Slaughter and C.K. Stead.

The competition’s reputation blossomed steadily, particularly under David Eggleton’s open-minded yet also perspicacious and uncompromising watch. In 2018, when I was the new editor of Landfall, I had an almost comically difficult time winnowing the field of ninety entries. In fact, at one point in the judging process, I wrote to the then publisher, Rachel Scott, with a cry for moral support.

Rachel understood. She dutifully included a POOR EMMA in her reply, and said, ‘Maybe there needs to be a book?’ Jokingly lamenting how few botched, scrambled, deathly dry or amateur essays there were (the dross that would have made the filtering process far more straightforward), I agreed that a book might be a good idea and suggested we could call it ‘Essay, Essay, Essay: What Do We Have Here?’

Clearly I was saving intellectual energy for re-reading and selecting. The wisecracks via email tapered off as I read and re-read the submissions, woke up in the middle of the night with my thoughts fossicking into the pleats or chewing over the rough hangnails of the arguments in some entries. But eventually I wrote to Rachel again with a triumphantly final cull of 37.

She told me to get tougher. Cut-throat, hard-arsed, no more Mrs Nice Guy, I wrestled the list down to 21. Still no go. Then down to 15. Encore, nope: anything more than ten would look indecisive for a prize announcement. So, once more unto the overreach – I returned to the pile and reconsidered.

I took some comfort from the fact that Rachel Scott was serious about the idea of an essay anthology. It wasn’t my lack of girded loins that made selection difficult: it was the high standard of the entries. Wonderfully, and in quick order, the concept was approved by the Otago University Press publishing board. We hoped that Strong Words: the best of the Landfall Essay Competition (a much better title than that first cross-eyed jest) might become a series; though I did think it was possible that 2018 was an anomalous year.

Happily, it was no freak aberration. Strong Words # 2 combined the best essays of 2019 and 2020; and now, in 2023, Otago University Press has produced the third volume in the series. Strong Words 3 showcases the intake from the past two years of the competition – years which have again been sterling. My co-editor Lynley Edmeades (the current Landfall editor) and I have each separately chosen half the contents – and definitely would have welcomed more, if various factors had permitted.

A double-headed editorial entity might sound like some daunting, slavering Cerberus-skulled gatekeeper. Yet my hope is that our different tastes and aesthetic styles mix in this selection, like fresh and salt water; so that divergent populations meet and mingle in a fertile, estuarine zone, and the collection should attract even more readers.

* * *

My co-editor Lynley Edmeades is not only a poet but also a serious and searching essayist in her own right. In 2019, I wanted one of her (anonymously entered) explorations of language and gender for the first Strong Words; she had to decline because there were other designs afoot for it. With a PhD in English Literature, Lynley has an interest in the avant garde, in formal experimentations, and in the essay as a place of openness and productive irresolution.

As she says in her article ‘Supposing (Un)Certainty: Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and the Queer Essay’, she is interested in slipperiness, in porousness, in the way an essay can hover ‘in between our conclusive and tidy notions of genre’ and the way it ‘works against essentializing answers and opts instead for supposition’.[1] The essay, she writes, ‘is a space to explore the possibilities of uncertainty [… ] It hovers in entanglements instead of seeking closure or tidy conclusions. It supposes, I begin to suppose.’[2]

In her judge’s report for the 2021 contest, won by Tina Makereti’s essay ‘Lumpectomy’, Lynley describes the contemporary essay’s permeability ‘as something of an antidote to the atomization and splintering that seems to govern our current emotional dispositions; essays can offer a salve from the dominant and dominating individualism of our age, by showcasing all its antonyms: relationality, vulnerability, hospitality. A place to come out from hiding.’[3]

I wonder, re-reading this, if in our current moment we need the carefully wrought essay even more for its contemplative thoughtfulness and its potential as a site of healing, and rather less than we need it for the ‘contentiousness’ encouraged in the competition’s website rubric. Many readers, surely, witness enough flashpoint reaction, dysregulated argument and deliberate, heated provocation on social media, with its mêlée of pile-ons and self-righteousness, often from bad-faith actors and false avatars.

During my own tenure in the judge’s role, I didn’t actively try to ferret around for the controversial. Yet my choices for the shared first prize in the year 2019 received a scolding personal letter from a correspondent disappointed in the winning essays, which he thought were solipsistic. In fact, both authors – Tobias Buck and Nina Mingya Powles – discussed issues of prejudicial judgements of character based on skin colour: a pressing socio-political issue much wider than the self, and one that is unfortunately both current and perennial.

* * *

Before I held the Landfall role, the essays I gravitated towards as a reader were usually on literary, psychoanalytic, or sometimes natural history subjects. I particularly loved essays on poetry and poetic form. Some book titles that still come back to me with the ease of formative songs are Part of Nature, Part of Us by Helen Vendler; Breaking the Line, by Helen Vendler again: Proofs and Theories by Louise Glück; Doubtful Sounds by Bill Manhire. Vincent O’Sullivan’s literary criticism, scattered throughout various works on Katherine Mansfield, had been a touchstone, since my late teens, of transporting non-fiction style: capaciously knowledgeable, critically insightful, compassionate, and alternately lyrical or sardonic as the point required.

In a more random walk, The London Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement, the New Zealand Review of Books and the electric jungle of the internet often lured me off to sink into the work of other essayists: Adam Phillips; Jenny Diski; Jonathan Franzen; Maggie Nelson; Jenny Zhang; Patricia Lockwood: John Lanchester; Arundhati Roy; Oliver Sacks; Ashleigh Young; Zadie Smith; Neville Peat; Jillian Sullivan; Loren Eisley. My willingness to branch out into reading essays on non-literary subjects was fueled by recommendations from canny readers (such as Barbara Larson, publisher at the former Longacre Press, where I worked from 2000–2010), and by the Landfall essay competition itself.

As a younger writer, I always devoured David Eggleton’s competition choices, and also his judge’s reports, which were piquant, concise, perhaps mini-essays in their own right, laced with epigrammatic lines that could serve as barometers of taste and an aspiring writer’s yardstick. Take this, for example:

The best essays are not an escapist form of writing, nor are they slab-like factual articles; rather, they engage with the word directly and are driven by personal passions. Theodor Adorno stated that ‘the law of the innermost form of the essay is heresy’: its purpose is to challenge us with literary evidence of a free mind in play […] Good essays declare themselves by exceeding the expectations of the casual but alert reader; they serve as a means of consciousness-raising, as a form of enlightenment.[4]

Of course, a judge isn’t exactly ‘a casual but alert reader’. A judge has to be steely and exacting about some things. What I found, when trying to hone my critical cleaver and shank my own longlists, was that I had to set aside essays that had gleams of potential but which definitely still needed an editor. In this sense it was quite different from choosing work submitted directly to Landfall. When the choice is between excellent, and excellent-plus, I had to admit to myself that some entries I loved, or on topics I thought were vitally current, were let down by glitches like not having an argument or opinion backed up with persuasive and credible evidence. Or they foundered on comparisons between, say, historical events and current social phenomena that were tonally discordant.

I had to bump otherwise engaging essays because of small eruptions to the reading trance (like a closing image that jarred against the preceding argument or vision); or because the drafts were badly proof-read, so that not only spelling but also meaning was mashed into an illegible pulp. Some essays used quotations totally irrelevant to the point; others had to be passed over because they were potholed by my pet, pet, pet stylistic hate. Not redundant repetition but dangling participles, which make sentences pratfall into unintended semantic catastrophe. (‘Sitting in the bath, the dog appeared at the door.’ ‘Trying on the dress, the bird flew past my window.’ ‘Wearing high heels, the cockroach ran up my leg.’)

So, yes, in a way, a judge does have to be a pedant. But they also have to be able to adjust their vision to and fro, from the texture of the language to the weave or arch of the argument: i.e. from the view of the jeweller examining gemstones through an eyepiece, to that of the hiker looking back at a full panorama, from the crest of a hill just climbed. They need to think not only about the subject territory, but also about the direction and layout of the points the writer contends; the fire and drive of the discussion; as well as, for sure, the topic’s relevance to keen, inquisitive, contemporary readers.

It’s challenging to outline an exhaustive set of criteria for what a judge might scan the entry field for. After all, under the skilled touch of our best writers, even the story behind a toenail clipper collection might seem enthralling.

* * *

Landfall also runs an annual essay competition for young writers. In 2015, Rachel Scott engaged help from the Irish Kiwi writer Dr Majella Cullinane, tasking her with developing marketing ideas for Landfall. Heading towards the seventieth anniversary of the journal, Otago University Press was keen to bring in more young readers. Majella suggested, says Rachel, that OUP developed ‘a younger competition, to encourage school-age teens to get to know and read Landfall.’ Essays were a growing genre, and a distinctive Landfall strength. ‘There was also definitely an element of wanting to encourage young writers to think critically and imaginatively, in the face of the massive impetus for them to spend their whole lives online.’

The contest was originally named in honour of the journal’s founder, Charles Brasch, who Scott says had a ‘predilection for commentaries’. From 2024 on it will be renamed the Landfall Young Essay Writers’ Competition, the suggestion of Sue Wootton, the new publisher at OUP. The upper age limit for writers will also extend: entries will be welcomed from writers aged 16–25.

Promoted to secondary school teachers around the country, the contest for younger writers can turn up profoundly mature essays that easily hold their own against entrants in the adult category. The youth competition contributes considerably to the vitality of the local form. This year’s winner was Xiaole Zhan’s essay on how music can shape perception of the body. In 2022 the winner was Ruby Macomber’s essay ‘Good Catholic’.

For Lynley Edmeades, ‘the best essays are both waterproof and leaky crafted and open’; and for her half of the selection in Strong Words 3, she sees the common thread being an engagement in ‘the act of learning’ which ‘implies an acknowledgement of the flabby, leaky and largely unknowable world beyond the self’.

What I wanted in my own quest was the sense that the author could unpack their area of expertise or experience with clarity and precision. I hoped to find an informed intelligence but also erudition worn in a light spritz – I didn’t want Landfall readers to feel cornered in the library stacks by tortured souls whose clothes and breath reeked with the odour of monomania. I sought essays that were either animated by a sense of urgency, curiosity, or enthusiasm; or that emanated a calm, reflective wisdom. I also hoped to find work that understood the power of metaphor and simile: deploying what poet and essayist Lynn Jenner recently called, in a creative non-fiction writing workshop in Ōtepoti/Dunedin, ‘the lightening strikes of figurative language’.

Every year, another astoundingly broad display of subjects fans out, shifting and dancing like a pride of peacocks’ tails. Strong Words 3 includes essays on the history of anti-Semitism; on dealing with breast cancer; on the toxic allure of cigarettes; on grief; on language acquisition; on recollections of childhood; on the elusiveness of the link between identity and gender; on the long aftermath of colonisation; on the nature of traumatic memory; and on working as a comedian while solo parenting.

And my thoughts on the general state of the essay here in Aotearoa in 2023? In the introduction I note the etymology of the word ‘essay’ – French for a trial, an attempt.

It seems to me the term encodes the genre’s own openness, its dual acknowledgment of effort and imperfection, and its constant striving for excellence. In the name’s very acknowledgement of the ongoing need to explore and understand, to revisit and rethink, it also ensures its own longevity as an art form. I think the robust health of the local variety, as shown here in Strong Words #3, cheers on that point resoundingly.[5]

* * *

The contributors to Strong Words 3 are: Maddie Ballard, Tīhema Baker, Rachel Buchanan, Jayne Costelloe, Lynn Davidson, Andrew Dean, Charlotte Doyle, Jessica Ducey, Susanna Elliffe, Bonnie Etherington, Norman Franke, Gill James, Claire Mabey, Tina Makereti, Alexis O’Connell, Sarah Ruigrok, Maggie Sturgess and Susan Wardell.

[1] Lynley Edmeades, ‘Supposing (Un)Certainty: Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and the Queer Essay’ Journal for Literary and Intermedial Crossings 7.2 (2022)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Lynley Edmeades, Judge’s Report, Landfall Essay Competition, Landfall 244, November 2022

[4] Emma Neale, Judge’s Report, Landfall Essay Competition, Landfall 232, Spring 2016. In fact, in her section of the Strong Words 3 introduction, Lynley Edmeades also quotes Theodor W. Adorno on the essay: perhaps a reassuring sign of continuity for future entrants.

[5] Emma Neale, ‘Open Fields’, Strong Words #3, p. 9

'I want you to think about what you would like to see at the heart of your national literature ' - Tina Makereti