The Best of Vincent O’Sullivan

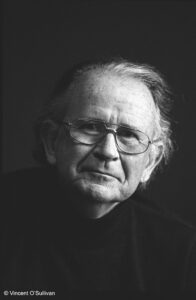

Vincent O’Sullivan’s last book, the poetry collection Still Is, was published in June. The poems, writes James Norcliffe, ‘are marked with O’Sullivan’s indelible signature: they are wry, witty, with conversationalist titles and tone belied by the layered irony and all but subterranean passion.’ We asked ten other New Zealand writers to choose their favourite book by O’Sullivan – a difficult task, given his prowess in poetry, fiction and nonfiction.

.

Vincent was a true polymath with talents spread over so many creative fields, yet each work rich in depth and understanding. Like so many others I was fortunate to have his friendship and support. The book of his I choose to mention here is the biography of John Mulgan Long Journey To The Border (Penguin Books, 2003). It displays Vincent’s rigorous scholarship, his psychological insight, his command of language and especially his empathy and support for others on the journey of life. Mulgan was a highly intelligent and accomplished man, yet conflicted in subtle ways. How well Vincent is able to understand and explain him. I re-read the biography recently and was comforted to hear Vincent’s voice again. He is never obtrusive in his works, but always discernible, and that compounds their worth.

Kirsty Gunn

Vincent’s novel Let the River Stand (Penguin Books, 1993) is on my list of favourite novels ever. I love it for its dense sense of atmosphere and landscape, as though the fiction has simply followed the contours of the place of its setting. From the moment it was published and I read it, I could feel the way this book was made slide straight into my soul.

My favourite has to be Us, Then (Victoria University Press, 2013) which won the Montana Book Award for Poetry in 2014. Favourite because I had the pleasure of presenting it to Vincent at the awards ceremony. I can still feel the warmth of his handshake and his softly murmured ‘Thank you’ which I repeated back to him as if we were playing ping pong. There were brilliant entries that year but when I reached the end of Us, Then I knew that Vincent could go to places that others couldn’t. He had techniques up his sleeve, a flexibility that extended itself with each new poem. I can’t say it better than Michael Hulse: Vincent had ‘a tireless affectionate scrutiny’ that never failed.

Vincent never ceased to surprise and break new ground. His very last book of short stories, Mary’s Boy, Jean-Jacques and Other Stories (Te Herenga Waka University Press) was published in 2022. It is a delight: measured, subtle, cerebral, mature and erudite. Control of language and elucidation of the most subtle human emotion and impulse is second to none. The volume consists of six long short stories, a now neglected form, and concludes with the startling novella ‘Mary’s Boy, Jean-Jacques’. From beginning to finish, the master is at work. Vale, Vincent. You are missed.

The book that best represents Vince for me is his last collection of fiction, Mary’s Boy, Jean-Jacques and Other Stories (Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2022), the novella that gives the book its title, in particular. This splendid riff on the tale of Frankenstein is at once a fond pastiche, a moving love story and a subtly subversive comment on modern cultural debates, all done with the skill of a master craftsman still, at 84, at the height of his powers. The scholarship, the wit and the great humanity of the man are there for all to see.

Majella Cullinane

For a year or so before Vincent published Mary’s Boy, Jean-Jacques, I used to meet him at Otago Museum cafe for lunch and we’d talk about what we were working on. At one such lunch, I discovered our mutual love for Shelley’s Frankenstein, and also that we both thought the book’s ending was pretty ambiguous. When he told me his idea for a story where the monster turns up in Fiordland I thought it was brilliant. The style of the novella’s language, the depiction of the landscape, and the deep empathy Vincent has for Jean-Jacques, was, in my opinion, the perfect sequel to the classic. He not only expands on the original but makes it his own, and uniquely kiwi.

.

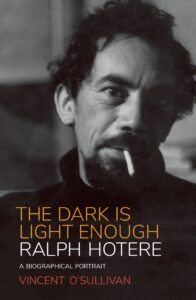

Apart from his poetry books, worlds in themselves in which I tread with awe, my favourite book of Vincent’s is The Dark Is Light Enough (Penguin Books, 2020), his biographical portrait of Ralph Hotere.

Both artists of the highest calibre, each spoke his natural chosen language of paint or words. They approached their work with humanity and humility. It seems to me that there was a similarity between them.

I think the poet and the artist saw themselves as workmen, just getting on with it in the best way they knew how. In a poem from The Movie May Be Slightly Different (Victoria University Press, 2011) I can hear them both in Vincent’s voice:

Shaping Up

.

Most of one’s life – the better part,

let’s say – we’re up to our wrists

in clay, liking that potter’s image

for what we’re handling, the glaze’s

rare shimmer defining it ours.

.

A lifetime’s, is that what we said?

The whirr between our palms. Get

the feel of it right.

And the word one

evening, ‘This is it, then. This

is the shape you’ve worked for. This

has to be it.’

Never enough stones handy

to pelt the thing.

.

I feel that Vincent’s work is true to the Ralph we knew. In its pages Ralph comes alive again, for me, as does Vincent himself via the ‘rare shimmer’ of his words.

Of Vincent’s poetry collections, Blame Vermeer (Victoria University Press) has a special significance for me. It was published in 2007–two years after I spent a week with Vincent (and Tusiata Avia) as guests at the Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam. During that time Vincent and I struck out for galleries and museums thereabouts, visiting Amsterdam and The Hague as well as making numerous visits to the Boijmans Museum, not far from our hotel in Rotterdam.

We rendezvoused one day at the Mauritshuis in the Hague, having arranged to meet in front of Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’. It was plain to me then, as it is now: Vincent’s poems can be like Vermeer paintings… Many are interiors in which the space between figures (or around a single figure) is carefully evoked, the tone, light and mood are masterfully adjusted and fixed in place.

Time is transfixed in Vincent’s poem ‘Blame Vermeer’, as it is in the painting that inspired it: Vermeer’s ‘The Milkmaid’ (aka ‘The Kitchenmaid’), 1657-8. Vincent was a great observer–of paintings as he was of people, of painterly technique as he was of human nature. He was also a brilliantly attentive student of narrative, as it pertains to paintings, poems, fiction and life itself. His writing was infused with a sense of wonder, as well as knowledge gained. So much to be carrying on with…

.

Blame Vermeer

A woman of thirty pours the inch or so of milk

left in a jug, sets the jug high on a shelf

inside a small cupboard because the children

from next door are to stay the night, she’ll

not risk their picking at its precious glaze.

She takes her ring from beside the tap,

slips it back onto her third finger.

She hears steps on the path.

Something

will happen after every painting for a long

time yet. It may have been war,

a sudden wrenching of implacable grief,

diseases arrived from the unburied,

children clattering in only days until

they are shunted east.

And the stranger

announcing, ‘There is something here,’ and her hand

on the lip first then the jug’s smooth curving,

it was lifted, so Jug & Woman

may have been the title again as it was and was

how many hundred times in that small

kitchen, its imagined canvas, the deluging back

of ordinariness so lovely, to what can one

compare it? And the steps always arriving.

It will happen next.

I found myself poring through all of the Vincent O’Sullivan books I own this morning, and there are many, with a mounting sense of frustration. The poetry collection of his that I love the most is defined by a single particular poem, and I cannot find it, or remember the title. I know it is about a woman standing at a window and waiting. But I know this is irrational. I have most of Vince’s books because I love the work, plus he insisted generously on sending me copies before I could buy them, so each one is a gift in itself and each to be treasured.

I have settled on Nice Morning for it, Adam (Victoria University Press, 2004). Straight away the title speaks to you, in Vince’s wry, laconic voice which echoes the common vernacular which he loved and understood. There is a love poem in it ‘As though’, which I like a great deal, but it’s not quite the one I’m after. But the book also contains another of my favourites, ‘River Road, due south’. Here the poet is on a bus, in the dark; the reader senses the movement forward, the figure in the night seeking answers, watching the familiar landscape through a particular lens, especially the river that has informed so much of his writing, ending with that quiet tenderness that was so often overlooked in Vincent’s work, an acknowledgement of love. It’s pure O’Sullivan.

River Road, due south

.

Much of my life it seems I have been on a bus

not so long after the late evening smeared

its flaring rag across the mirror of the river

and the glint that follows of water lying

heavy, and a house on the far side

with a light that burns on the back porch

and a flag of expanding yellow pouring

from the side of a window without a curtain

is as lonely I suppose as a house can seem

as you watch from the river’s far side

and it comes up from the reflecting distance

and holds level there across the water floating

its spilled silence, and drifts back and behind

so it’s night again, night so you can take on trust

the current’s muscling twenty yards off

and the house and the house’s reflection

and the kitchen smells like words you wish

you could easily remember, they are there

as your own sitting in the bus’s hollow

pulse, the dashboard a distant altar

the driver believes in, believes will charm

us past Rangiriri and Taupiri and into

the string of lights that thicken to suburbs

and into the clatter of someone else’s music,

and the house and the river and the dark

either side of the house and it’s lights floating

more important than any star, is back there,

taken by night, and where you were.

.

I have chosen a poem, rather than a collection – ‘The Child in the Gardens: Winter’.

Vincent always reminded me of my pop. He had the same happy-sad eyes. And he spoke in the same tones too, and with the same hint of old time sorrow.

It was as though he understood and loved the vernacular of my pop’s world — a time when Pākeha were growing into themselves, caught between Europe and somewhere else — long before they had any thought of being Pacific.

Listening to him again his voice is full of hedges and lanes and vegetable gardens in the back yard. He gave these things dignity, raised a glass to their ordinariness, and to their longing. At the same time he always seemed to wonder (ever so gently) how they could be more.

Moe mai e hoa. Ngā mihi nui. Ngā mihi aroha.

The Child in the Gardens: Winter from Nice Morning for It, Adam (Victoria University Press, 2004)

.

How sudden, this entering the fallen

gardens for the first time, to feel the blisters

of the world’s father, as his own hand

does. It is everything dying at once,

the slimed pond and the riffling of leaves,

shoes drenched across sapless stalks.

It is what you will read a thousand times.

You will come to think, who has not stood

there, holding that large hand, not said

Can’t we go back – I don’t like this place.

Your voice sounds like someone else’s. You

rub a sleeve against your cheek, you want

him to laugh, to say, ‘The early stars can’t hurt

us, they are further than trains we hear

on the clearest of nights.’ We are in a story

called Father, We Must Get Out.

Leaves scritch at the red walls,

a stone lady lies near the pond, eating

dirty grass. It is too sudden, this

walking into time for its first lesson,

its brown wind, its scummed nasty

paths. You know how lovely yellow

is your favourite colour, the kitchen at home.

You touch the big gates as you leave,

the trees stand on their bones, the shoulders

on the vandaled statue are huge cold

eggs. Nothing there wants to move.

You touch the gates and tell them, We

are not coming back to this place. Are we, Dad?

'I felt energised by the freedom of 'making things up’' - Maxine Alterio