An Interview with Albert Wendt

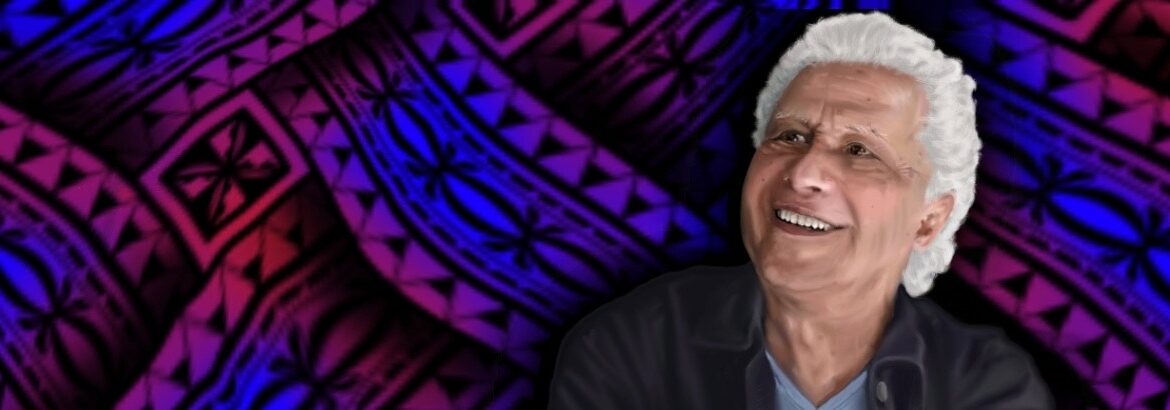

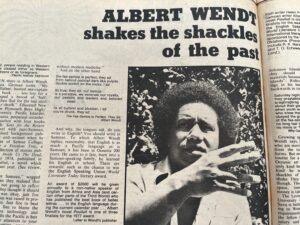

Born in Apia in 1939, Maualaivao Albert Wendt is an iconic figure in Pacific and New Zealand literature, the author of novels, story collections, poetry collections, critical essays, creative nonfiction and plays, and also an accomplished visual artist. In An Indigenous Ocean, Damon Salesa describes Wendt as central to the ‘Pacific Way’ movement of the 60s and 70s, a group that included Te Rangihīroa Sir Peter Buck, ‘Okusitino Māhina, Grace Molisa, Tui Ātua Tupua Tamasese, Konai Helu Thaman and Futa Helu. Along with Epili Hau’ofa and his ‘sea of islands’, Wendt, Salesa argues, ‘was the first explicitly to re-envision the island Pacific as a “New Oceania”.’

Wendt was the first Samoan writer to publish a novel, and the first Pacific Islander to be appointed a Professor in University of Auckland’s English department. Since ‘the rise of Pacific Literature in late 1960s,’ Selina Tusitala Marsh has written, ‘little happened in the field that wasn’t connected to this writer, artist, anthologist, teacher, and scholar. Samoan by birth, Oceanic by nature, Albert has taught in Samoa, Fiji, New Zealand, and Hawai’i. Wave after wave of his creative and critical writings have washed up on the intellectual and artistic shores of Oceania for over five decades. His writings have changed the way Oceanians think about themselves and how others think of Oceania. In his wake, Albert has left generations of writer-scholars who have gone on to write, teach and make art throughout Melanesian, Micronesia and Polynesia, and in the global Pasifika diaspora.’

Pala Molisa’s mother studied with Wendt at the University of the South Pacific in Suva, Fiji, just after Wendt’s first novel, Sons for the Return Home, was published. In an essay about Wendt in Nine Lives, Molisa describes the writer in the mid-70s as ‘young, Samoan, fiery and free’, teaching his students to reject ‘colonial boxes by finding their own political voices and pursuing their revolutionary dreams.’

Since the early 1990s Wendt has been based in Auckland, although he’s spent long periods of time teaching, speaking and writing overseas; the four years at the University of Hawai’i he describes, in Out of the Vaipe, the Deadwater, as ‘some of the happiest and most productive years of my life.’ He lives in an old Ponsonby villa – home to Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage in his trade union days – with partner Reina Whaitiri, with whom Wendt has edited several groundbreaking anthologies of Pacific poetry.

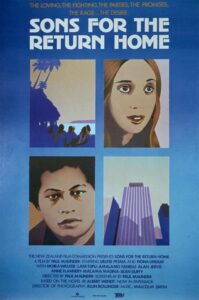

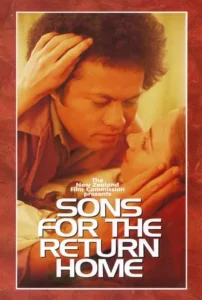

This interview – undertaken by his nephew, Todd Barrowclough – took place in this house, with its lush garden and broad veranda. It was commissioned to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Sons for the Return Home. An exploration of diasporic experience and familial conflict, and the relationship between a Samoan man and Papālagi woman, Sons was a publishing sensation and popular success. The ‘picture of race relations is very authentic and moving,’ wrote Felise Vaa in The Samoa Times, ‘and if the book has managed to bring this to the public’s notice, then it is a landmark novel.’ In Islands, Elsie Locke declared it unlikely that anyone but Wendt ‘could portray the people of the two countries with the honest assessment and generous humanity he brings to this novel.’ K.O. Arvidson, in Landfall, called Sons ‘a story of remarkable complexity’, and recognised what the work of Māori and Pacific writers demanded: ‘a circumspection and a breadth of cultural reference for which New Zealand criticism is largely ill-prepared.’

Sons, James Bertram wrote in the Listener in 1978, ‘sketched a scenario of confrontation that none of us – least of all politicians or government agencies – can afford to neglect. The book set out to shock, but with the justification of strong feeling and a good deal of genuine moral indication.’ A film version was made in 1979 and the novel remains in print fifty years after its debut. Wendt has won many awards during the six decades of his career, including national book awards and international honours. In 2013 he was made a Member of the Order of New Zealand, our most senior honour.

TB: In Out of the Vaipe, the Deadwater you say that your writing life ‘has been a process of learning, through my writing, the depths of Samoan history and culture; the writing has been an attempt to discover it and to shape it in my own way.’ Where did your love for writing come from?

AW: I was lucky to be raised by my grandmother and family and I loved listening to the stories they’d tell. Since I was 13, I’ve more or less been able to do what I want to do. Just to do enough work to get through and have the brains – and having other people pay for my education. I was raised by a father, mother and grandmother who believed that education was the way out of being poor. My siblings and I had a tradition of getting scholarships and going overseas to study. Someone once said of our family: ‘Oh, the Wendts. If you put all their degrees together, you would need a truck to carry them.’

New Plymouth Boys High School, Main School Buildings, 1957.

TB: After gaining one of only nine scholarships available to Samoan students at the time, you came to New Zealand and attended New Plymouth Boys High School (1952–57). What was this experience like for you as one of the few Pacific Island students?

AW: To go straight into boarding school – a very highly regarded boarding school where everything was paid for – was a bit frightening. I didn’t know anything about Pākehā culture then.

I got the scholarship when I was thirteen. I was fortunate and privileged but in some ways I wasn’t. I missed out on a hell of a lot of growing up in Samoa with my family and knowing the fa’a Samoa. Still, I gained a lot. Very few people have had the experience I had.

At school in Samoa and at New Plymouth Boys High School, teachers were always very good to me. I was shy, quiet and withdrawn but my teachers knew I was very bright, so they made exceptions for me. They’d just leave me to do what I was doing. I started to come out of my shell when I went to Ardmore Teachers College [in 1958] because they allowed you to be more open, to be political and anti-racist.

After I finished training college I went to Victoria University to study history. I was a mature student in many ways. I had published writing already and was continuing to publish, so they’d make exceptions for me but did their best not to show favouritism. When I handed assignments in late, they’d tell me not to worry because I had a lot of other work on my plate. I got my degree in history but I ended up getting a professorship in English later.

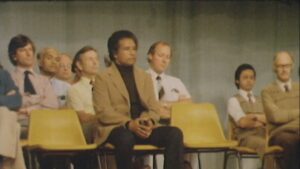

Albert Wendt on the teachers’ podium during assembly at Samoa College. Sourced from TPPLUS.

TB: Did publishing your writing early on help you find your place in Aotearoa more generally?

AW: Yes. It helped people be more tolerant of me and what I was doing. They would go out of their way to accept that I was only getting Cs for a lot of the courses I was doing. But they knew that I was getting A+s for my answers to questions that I was interested in. I wouldn’t care about the rest of the paper. I’d just do enough to get through.

.

TB: You were reading a lot during this time too. There are references in your early work to Chinua Achebe and Albert Camus, among others. A poem in your first poetry collection, Inside Us the Dead (1976) is called ‘To My Son on the Tenth Anniversary of Independence’ – a nod to James Baldwin?

AW: There were many things I was experiencing that found their way into my books. I was very heavily influenced by the existentialists and it came out in my own work. My reading helped deepen the work and make it more complex.

.

TB: Did you feature aspects of fa’a Samoa in your work to connect you to your home and your aiga while living overseas?

AW: Yes, I did. I’d come across something and would tell myself I had to find out what it meant. I couldn’t just misrepresent Samoan culture because people would think I didn’t know the ways.

TB: You wrote your first novel, Sons for the Return Home, over a few years while serving as principal of Samoa College, a post you held from 1965–74. Other than wanting to make sense of your early time in Aotearoa, what motivated you to write the book?

AW: I was compelled to write. You know, the compulsion to write always comes first. Then you sit down and either write a story or poem and it leads to something else. The idea in my head led to this novel.

I wanted to make Sons a romance with a typical plot: boy and girl fall in love with each other. It’s an interracial relationship, so the complications that come with this were there. And I wanted to keep the narration quite straightforward and poetic. I was quite surprised when it became a hit after it was published. A lot of people read it and it’s still in print today which is quite something for a book in New Zealand.

.

TB: Hone Tuwhare published his first poetry collection, No Ordinary Sun, in 1964. In 1972 Witi Ihimaera published the story collection Pounamu Pounamu, followed by his first novel, Tangi, in 1973, the same year as Sons. In fact, the Landfall review of your novel described 1973 as ‘a watershed year in the development of Polynesian literature.’ Two years later Patricia Grace published her story collection, Waiariki. Do you think it helped you as a Samoan writer to start publishing at the same time as these writers and others in Aotearoa?

AW: Yeah, it was good coming up with them. Witi tried his best to publish a book before me and he did!

.

TB: Sons was one of the first books written by a Pasifika writer to be published in English, along with other works such as The Crocodile by the Papua New Guinean writer Vincent Eri released in 1970. When you were writing your book, did you consider the significance of it?

AW: No. I was just thinking of the story itself. It was going to be a novel and it was going to head in this or that direction. How is the romance going to play out? How will it end?

When the novel was published, my hope was that a lot of people would read it, which is what happened. A lot of people read it because it was a romance – especially young people, even though the material is quite adult. This was probably one of the reasons why the novel was a hit in high schools. Many parents didn’t like their children reading it, and I believe that in some schools the book wasn’t allowed on the syllabus. Kids used to have a copy of the book and would pass it around. After my time as principal at Samoa College, students would tell me privately that they did this.

Years after Sons was published, I remember visiting a girls’ school here in Aotearoa, with mainly Pacific Island students in the class. They told me they really enjoyed studying Sons as a prescribed text, and that it was the first book they’d seen themselves in.

It was one of the first novels to be very honest about Pacific Islanders in New Zealand, about their experiences and the race relations of the time. But it was also a simple love story that just happened to involve a Pacific Islander and a Pākehā woman, which made it different from one featuring two Pākehā or two Samoans. I enjoyed writing it and didn’t really bother with the negative criticism. Well, some of it hurt a bit but I didn’t care. I think the sexual content was way ahead of its time.

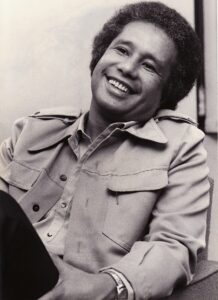

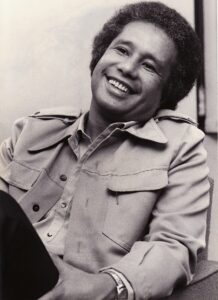

Photo of a young Maualaivao Albert Wendt, supplied by his family; sourced from Pantograph Punch.

.

It was written by a very young man. I wouldn’t write a book like that now. I’m 83. It’d be a different book, a different love story, a different way. It was a young book written by a young man about a love story between young people. It gets complicated because love is complicated. And death and fear and working out complicated emotions and complicated things – you just can’t sit down and treat it like a maths equation where one plus one equals two. Boy meets girl – now what happens? So, you figure how much to put in and leave out.

In most ways, fiction leaves out more than it has in it for the reader to make connections between things. The better you can do that, as a writer, the better [the work] is. Some of the writers I don’t like are the ones who overwrite and talk down to readers.

A lot of people in Samoa and New Zealand attacked me privately but – because of my status or my politics – they wouldn’t do so publicly. They knew I wouldn’t take it and I’d say something. I continued to write what I wanted to write. I had nothing to lose. I felt I had something to say. It was also good to get the feeling that people were reading my work, whether they were valuing it or attacking it!

TB: Some Samoans objected to your depictions of sex in the novel along with aspects of fa’a Samoa related to the Church. In one scene you highlight the politics of fa’alavelaves (obligations) – specifically the way some aiga use financial donations to their churches to one-up others and display their wealth and success. This criticism was as close to home as it can get. How did you navigate this?

AW: When you’re attacking societal institutions in your work, a lot of people are bound not to like it. One intention in writing books is to expose things, to show what people are – all their pretension and hypocrisy. Most societies have double standards: a public standard and a private one. It’s nothing new.

.

TB: You’ve said that Sons is your most autobiographical work, as first books often are. How much of the story did you actually take from your life?

AW: It was basically the relationship I had with my wife at the time [Jenny Whyte], but it’s not exactly the way the relationship was. Most writers have to use some of their experience. A lot of people told her they were sorry that I put her in the book. She just told them that they better ask me who the woman is!

All fiction is autobiographical to some extent. You would have had the experience of something vicariously or first hand and know something about it.

.

TB: What was the process around getting Sons published?

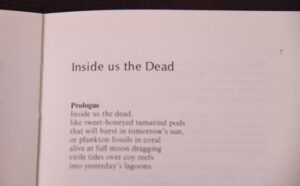

AW: After I’d published a few short things, my publishers wanted me to write a novel. I told them that they could publish Sons but they had to publish my collection of poetry (Inside Us the Dead) and some stories too – Flying Fox and the Freedom Tree (1974).

They told me my work wasn’t going to sell. I said, I bet you you’re wrong.

.

.

TB: So, you had some idea that Sons and your other early work would have an impact?

AW: Yes, because there was nothing apart from books by anthropologists and sociologists out there. It’s worth reading these but they’re written from another viewpoint, even though they pretend that it’s from the inside, from the culture. Plus, even if you’re from inside the culture you’re still just writing from your viewpoint.

The more individual the book is, the more worthy it is in many ways, for me, because the writer’s not pretending to be someone else.

.

TB: In quick succession you also published the novella Pouliuli (1977) and another novel, Leaves of the Banyan Tree (1979). You edited Lali: A Pacific Anthology (1980), a showcase of English-language work by writers from across the Pacific. All this time, you worked first as a school principal and then as a lecturer at the University of the South Pacific. You were married and raising a young family too. How did you find time to write and publish this frequently early in your career alongside these other commitments in your life?

AW: At university, in many ways, you get time to do your own research, and the writing was my research: it was part of the job description. That’s what I liked in my academic job, even though it was a lot of effort. Plus, when I was young, I had a lot of energy and focus.

Universities get a kick out of their staff making a name for themselves because this also gives them kudos. The University of Auckland loved having me and Witi Ihimaera on staff in the English department.

TB: Because of Sons, and your subsequent writing and editing, you were spearheading the new Pacific literature. Did you feel the pressure of expectation, the pressure to represent the Pacific and its cultures?

AW: The pressure I felt was about how I was going to publish my next book. Being called the first Samoan writer – you know, to be the first one, it was okay. The thing for me though is you’ve got to write books. And it’s good that people liked reading Sons and that young people liked it, but I didn’t particularly care if they didn’t. I never depended only on writing to make a living and to feed my family. So, I was fortunate in that way. But the writing was a lot of hard work.

.

TB: Did criticism lessen as your career progressed?

AW: Yes. People got too scared to say anything. But this was bad as well because people hid how they truly felt. Nobody said anything in public when I was around but then I would hear about their feelings later. People used to joke in Samoan: ‘The professor is coming to talk’!

The important thing for me was to get stuff written. If I needed money from writing to stay alive, I’d have written more.

.

TB: There are passages in Sons that read as if they’re fale aitu performances. For example, in the scene where the narrator and his girlfriend deliver mail, they put on the voices and airs of colonials to mock them and their racist worldview. You also include passages of myth and sections where a character relays history and stories to another – instances which echo the fagogo style of storytelling you grew up with. Were you surprised when people said what you were writing was a new way to tell stories?

AW: I was quite pleasantly surprised. It was a new way for those unfamiliar with Samoan stories, but our people have been telling stories this way for a long time.

If you can turn a story into something that other people understand and value, you’ve turned it into a sort of myth, a variation of a universal story. People go through the same experiences. Love and death are basic themes, but each culture tells the story differently.

It just happens that I know a lot of the mythology. Stories are about other stories are about other stories, and they just keep going on. It’s like when someone picks up a book and says, ‘Oh, man, I’ve read this before. I know this is about me.’ But the story is set in Russia. We have universal stories. We all live, fall in love and die. We go to heaven or go to hell – or don’t go anywhere.

.

TB: You’ve talked over the years about how you need to get the sound of your stories ‘right’ before you show them to the world. How do you do this?

AW: I’d read what I’d written aloud and if it didn’t work, I’d rewrite it. I asked myself how I’d like the narration to flow. If it’s not going well, you can tell.

I read aloud to myself. Very rarely did I read my work out to others – except my publisher. After I’d sent them a manuscript, they’d tell me there’s too much of this or too much of that. But it was totally up to me if I accepted the feedback or not.

.

TB: What’s your writing process?

AW: I’m not someone who can write regularly. I don’t have a daily writing schedule. I only write when I feel like it, but once I get into it, I can go for days or weeks.

When my kids were young, they’d have their friends over to the house to play. I’d overhear my daughter telling them to be quiet and go outside because I was busy writing.

When I lose interest in writing one thing I go to the next thing. I’ve never had to make a living from writing, so I could do things this way.

.

TB: Is this why you wrote your Commonwealth Writers Prize-winning novel-in-verse The Adventures of Vela (2009) on and off over 30 years.?

AW: Yes. I could have finished it in a couple of years, but I just enjoyed revising it. Finding new things to include. With Vela, I asked myself what would happen if this guy has all these adventures such as fighting the gods. It’s based on the Maui saga. Every culture has some version of the mythology of the hero versus the gods – except in Vela the guy is very well-educated. A lot of people – including Reina, my partner – think it’s my best work.

.

TB: This go-with-the-flow approach characterises much of your work, doesn’t it?

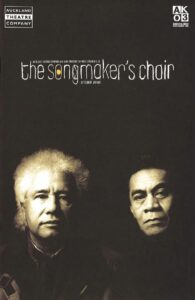

AW: With The Songmaker’s Chair (2003) I thought I’d write my first play. I thought it’d be good if I had some music on the stage and build the story around a chair. I’d include symbolic things like the chair, the structured family, how their life changes in New Zealand. Then the play became bigger than I’d thought.

I think there’s a part of The Songmaker’s Chair that my editors wanted me to change because it sounded too much like a university course. I said no. It was aimed at my people so they could understand their culture. The play was deliberately educational. I didn’t care if it didn’t suit the typical staging of plays.

.

.

This is what audiences really loved about The Songmaker’s Chair. Some people who saw it told me that they didn’t know any of this – even the Samoans raised in Aotearoa. They thought they should go home and ask their parents about it. Some of them brought their parents to see the play, and their parents loved it because it was about their generation of migrants.

A lot of this generation was ashamed of their culture and wanted their kids to learn English as fast as possible. They asked why they were wasting their time learning Samoan things, until they regretted it later, when their kids couldn’t speak their own language and started acting like Pākehā kids.

Sometimes I deliberately set out to write a story and sometimes when I start, I then think: oh, this isn’t a good idea. What about making it a poem? Then I hit another line and think I have to go bigger. But of course, the long novels are planned and thought about for a long time.

I’m a bit of a lazy writer.

.

TB: Why do you consider yourself lazy?

AW: I could have written more, you know, but I was busy with teaching as well. I never had long stretches of time to write, or had the urgency to write. I think there was still enough time for me to have written a lot more than I have. Though I could’ve written a hell of a lot more and it not have been any good. It’s rewarding that most of the work I’ve done is highly regarded by people – even the people who attack it.

I’ve always been interested in and love reading. So that’s really what it is: you set out to write something you want to read. Before all the Indigenous stuff came out, I read everything: the Russians, for example. When African and Asian writers began publishing books in the Sixties, I read that and taught a lot of it too. After that, work from the Pacific started getting published and I was helping to get a lot of it out there, and encouraging younger writers.

.

TB: You’ve also edited anthologies of Pasifika and Māori writing over your career, notably the poetry anthologies Whetu Moana (2002) and Mauri Ola (2010), as well as Lali: A Pacific Anthology (1980). Was this part of your mission, to develop writers and Pacific literature?

AW: I’ve done my own work, and helped other writers get their work published and get them started. A lot of people looked at the Pacific as an empty space without cultures and literature. You have to get rid of the racism because there’s a lot of it. How can our people have no culture, no literature?

Some particular cultures and communities are very good at nurturing painting; others sports. A lot more of our people are writing and creating art now which is good to see.

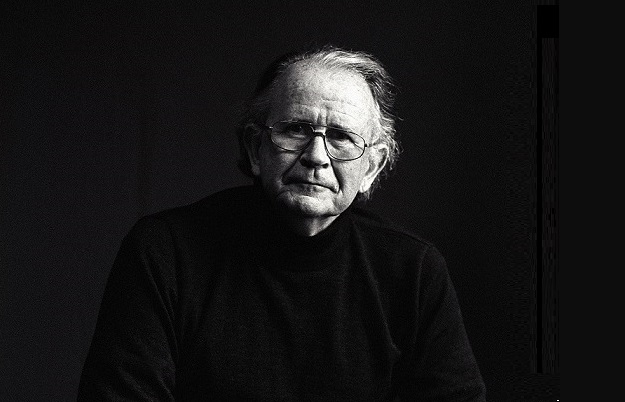

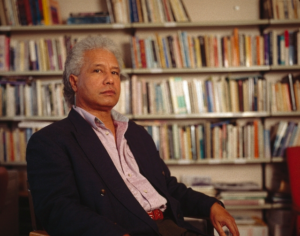

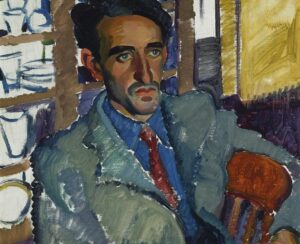

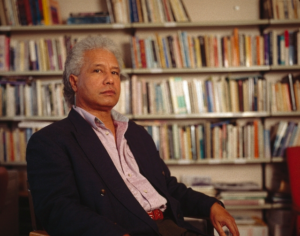

Albert Wendt, 1996. Photo credit: Hamish McDonald.

TB: How is your success as an artist impacted the way others see and engage with you?

AW: Everywhere I go in Samoa, as soon as people see me, they think, Oh the professor knows far more [than us] so we better not say anything. They get intimidated until I ask them something like ‘What would you like to drink?’ and they know I’m just joking away.

One time I was asked to speak at an end-of-year prize giving at the National University of Samoa. I was waiting at the back of the gymnasium before I was called up. This young pastor came up to me; he knew who I was. He introduced himself and told me that I used to teach his uncle at Samoa College.

He was speaking to me in English and I kept responding in Samoan until he got the message! See, a lot of Samoans don’t think I can speak the language, so they get a surprise when I start speaking colloquial Samoan.

And then a woman who’d made a speech for the students at the ceremony got up and said, ‘Oh, Professor Wendt used to teach my grandfather. My family have always known him as a member of our family even though we’re not connected in the fa’a Samoa way. We all want to be part of his family.’ I find this kind of attention embarrassing.

One time I made the mistake on a walk to downtown Apia. It was mid-morning and I was heading to a coffee bar that was owned by an ex-Samoa College student; they’d told me to come down. By the time I got there, 20 or so people were walking with me. They were all ex-Samoa College students and saw me walk past their workplaces. So, we all went to the coffee bar together and took over it. People were very happy.

You know, when these things happen it’s very pleasant but I also sort of pretend I’m someone else.

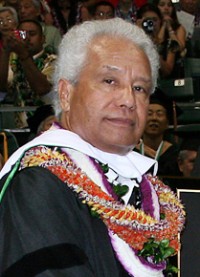

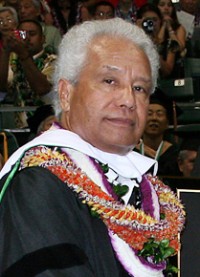

Albert Wendt in 2009, awarded an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters by the University of Hawai’i.

.

TB: Has the gap between your public and private selves been difficult to navigate?

AW: It was hard. You just got to be careful. Don’t do anything bad, don’t show off. Don’t take it for granted that you’re important.

.

TB: Your most recent books – the novel Breaking Connections and memoir Out of the Vaipe, The Deadwater: A Writer’s Early Life – were both released in 2015. Do you miss writing?

AW: I do, yes. Out of the Vaipe contains some of the best prose I’ve written.

.

TB: Your poetry collection The Book of the Black Star (2002) features poems and drawings which is an interesting mix.

AW: I just set up the easel then I start doodling around on paper. Sometimes I think about what I’m going to paint before I start. The next day, I go and change the whole painting.

It’s exactly like when I’m writing a novel. You can see the writing and the details in the painting. You make one change and other changes follow; it changes itself.

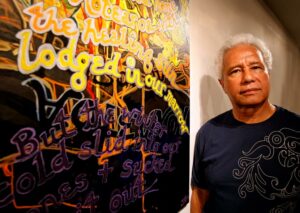

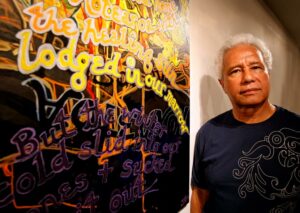

Wendt with one of his works at the McCarthy Gallery in Auckland, 2008.

.

TB: Are you writing now?

AW: Not at the moment, no. I still write emails and on my Facebook page. But no, I haven’t written something like a poem for a while. But I think I’m close to writing something. I always get a feeling. The urgency to write isn’t there anymore, but hopefully I’ll sit down at some point and write again. I have a few more years left.

.

TB: And this new work might be poems, yes?

AW: Yes. The poems will be partly a continuation. All my ideas will always be part of what I’ve already done. If I look back on all my work, I’ve been the same person doing it. There’ll be stuff in all one’s work that one has covered before.

.

TB: Looking back on your career, how do you feel about it?

AW: It’s been a satisfactory life. I’ve had a very privileged life. Not many people have the life that I have had. And I’ve earned it through my brains and hard work. I’m lucky that I’m very good at what I do – well, I think I am.

I happen to have been in certain places at certain times; having the scholarship scheme when I was 13, being able to return to Samoa as a school principal when I was only 29, becoming professor of English at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji, among other things.

I’ve been very lucky in my life even though there’s been a lot of pain. I mean, over the years, there have been people in my family who’ve died – my mother, for example. Everybody has pain. It’s been a good life, even though I complain about politics and inequalities. I’ve always been very political.

.

TB: You’ve said in the past that you used to be an angry young man before you mellowed in middle age.

AW: Well, it wasn’t me who said that. Other people said that I was the Angry Young Man of Oceania.

.

TB: How do you how do you see yourself now?

AW: I’m the Angry Old Man of Oceania.

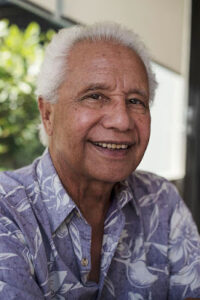

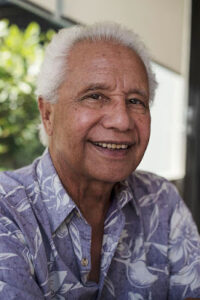

Photo credit: Raymond Sagapolutele.

.

.

.