International Women’s Day:

Writers Celebrate Writers

Nine New Zealand women writers talk about the other women – and their books – that influenced and impressed them. The writers canvassed here are: Lynley Edmeades, Charlotte Grimshaw, Karyn Hay, Selina Tusitala Marsh, Paula Morris, Catherine Robertson, Elizabeth Smither, Alison Wong and Briar Wood.

Lynley Edmeades

Perhaps the lesser-known younger sibling to Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Everybody’s Autobiography was written several years later, in 1937, and is said to be a continuation of the earlier ‘memoir.’ I use scare quotes here as even now, in the rather genre-fluid literary world we live in, it is hard to categorise this book. Stein – in her writing and her life – shirked many frameworks of expectation: her memoir isn’t a memoir as much as it a series of ‘rhythmic essays’ (what a genre!), which are, equally, stream-of-consciousness literary experiments. Across her life’s work, she attempted to capture something of the ‘excitingness of pure being,’ or, what she called the ‘continuous presence.’

Gertrude Stein in 1926. Photo credit: Man Ray

In Everybody’s Autobiography, Stein pursues this ontological experiment via memoiristic observations. It is perhaps a precursor to Annie Ernaux’s brilliant ‘collective autobiography,’ The Years, which also slips and slides between genres, mixing the first person with the collective ‘other’ with such aplomb that it has perhaps driven the personal essay to hide under a large rock for the foreseeable future. It is also where Stein famously wrote, ‘there is no there there,’ which, like much of Stein’s work, sends language spinning into glorious webs of malfunction and misfire, always casting light on the absurdity of our attempts to fix reality within it. An autobiography is an autobiography, is maybe an autobiography, is probably not an autobiography. Which is why I love it.

Lauris Edmond. Image via The Arts Foundation. Photo credit: Robert Cross

I was given Fifty Poems: A Celebration by Lauris Edmond (1999) by a dear friend when I left New Zealand for India in 2004. I didn’t then know of Lauris Edmond and had just started dipping my toes into New Zealand poetry (just as I was to leave for what ended up being four years abroad, in India, Nepal, Bangladesh and then London). I still have this same copy on my bookshelf that I reach for now: it travelled with me over those solitary years and was subsequently lugged from flat to flat, city to city, to finally wind up in the bookshelf of the house I hope I won’t have to move from any time soon. Opening it conjures up all those days and nights spent in foreign lands, homesick, nostalgic, lonely, building that peculiar interest in one’s own country that can only be ignited by distance (and a good dose of naivety)

Edmond so accurately conjured up the Wellington I’d just left behind, with the specificity of her ‘Outside the Public Library,’ or ‘Driving from the Airport,’ and lines like ‘the drowsy gorse on Varsity Hill.’ But it’s less her evocation of place than her irreverence that stood out to me then, and still strikes many chords for me today. Lines like ‘I saw a woman singing in a car/opening her mouth as wide as the sky, cigarette burning in her hand…’ and ‘yes yes of course I am hard to please –/yet I can see this quiet sky/with the evening in it…’ somehow gave me permission to notice and for the noticing to be enough. As if her poems were saying: just do the looking, the listening, and the interesting parts will follow. Reflecting on that now, I realise how much of my own writing has been tightly tethered to that core philosophy.

Charlotte Grimshaw

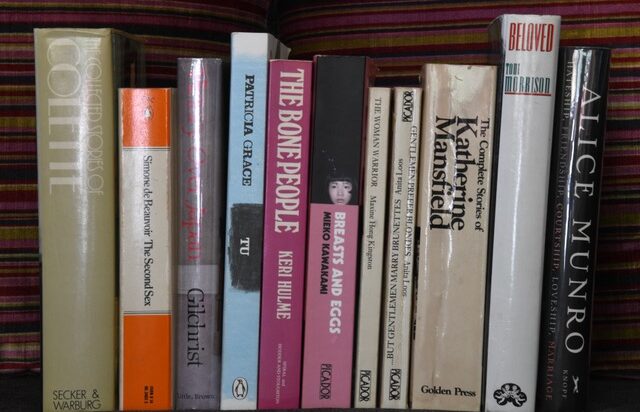

When I was starting to write fiction, I returned many times to The Collected Stories of Katherine Mansfield. I was excited by the brilliance of Mansfield’s prose, and I loved the wit, style, beauty and originality of her sentences. I was living in London when I wrote my first novel, and stories like ‘At the Bay’ intensified the nostalgia for New Zealand that was the driving force of my writing.

Catherine Mansfield. Photo credit: Ref: 1/2-002594-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22601543

I thought no one could match Mansfield until I discovered Alice Munro’s collections, Hateship, friendship, courtship, loveship, marriage and The Progress of Love. I was fascinated by Munro’s skill at finding the extraordinary in the mundane. She conveys so much by suggestion, and there’s wonderful precision in her prose. I read and return to her collections for lessons in structure and economy. The writing appears effortless, yet she builds intensity until simple prose begins to carry layers of extra implication, in the same way that the best poetry manages, mysteriously, to radiate meaning somehow beyond itself, beyond the words. There’s always a dry wit operating, and a benign view of human craziness, but when she wants to, she can shock with cold, hard force. Stories like ‘Family Furnishings’ and ‘Fits’ are great examples of layering, precision and control, and the ability to deliver a real punch.

Alice Munro. Image via the New York Times. Photo credit: Ian Willms

Karyn Hay

I’m going to do this by feel. By shining a torch down the murky lane of memory. No Google, no Wikipedia; those well-oiled tools of the writer. No inflated and entirely untrue recollections of exactly how much certain passages, certain women, influenced me, because, actually, I can only remember how these books made me feel. I’ll just have to use words for the words I don’t have. These are adjectives, nouns, phrases, a jumble. Like my memory.

Enid Blyton. Photo via https://www.enidblyton.co.uk

Enid Blyton The Famous Five and The Secret Seven

They’re not kidding when they say, ‘Turn off the light! No reading!’ And when they’ve gone you’re dead still, listening intently in the dark, and then slowly, you slowly reach under the pillow and slide out the torch and the book.

Fear

Stealth

Getting Caught

Obsessed

Transported

Adventure

Simone De Beauvoir. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

Simone de Beauvoir The Second Sex

Older now. I can read when I want. Kafka, Hesse, Baudelaire, Sartre, men’s words …

Intrigue

Disbelief

Sophistication

A bun!

Fuck

Keri Hulme in Ōkārito in 1998. Photo credit: Ans Westra

Keri Hulme The Bone People

Insight

Surprise

Truth

Myth

Here

Selina Tusitala Marsh

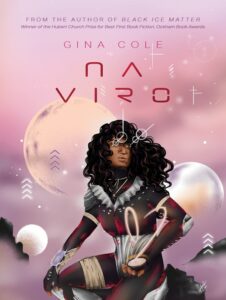

Samoan-New Zealand poet and performer Tusiata Avia at the 2021 Ockham NZ Book Awards with her award winning collection The Savage Coloniser Book. Photo via Stuff.co.nz

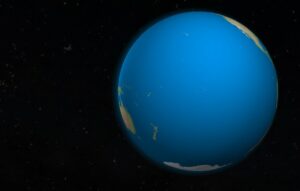

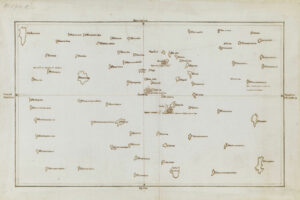

I am captured, neh, enraptured by Tusiata Avia’s The Savage Coloniser Book, her fourth collection of poetry (and winner at the 2022 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards). It deals with savage topics savagely, courageously, and she’s unabashedly brutal in her approach to the aftermath, and ongoing nature, of colonialism. We both have anti-homage poems to James Cook, the icon of European discovery of our savage selves in the ‘Pacific’. Mine’s called ‘Breaking Up With Captain Cook’. I first performed it in 2018 at the British Library, in response the exhibition of Indigenous and oceanic artwork created to mark the 250th anniversary of the first of James Cook’s voyages. Paula Green published it on Poetry Shelf. My first lines are:

Dear Jimmy,

It’s not you, it’s me.

Well,

maybe it is you.

We’ve both changed.

When I first met you

you were my change.

Well, your ride

the Endeavour

was anyway

on my 50-cent coin.

I’m playfully acerbic in my account of falling in love, then out of love, with Cook.

Avia’s version is titled ‘250th anniversary of James Cook’s arrival in New Zealand’ and her first lines are:

Hey James,

yeah, you

in the white wig

in that big Endeavour

sailing the blue, blue water

like a big arsehole

F… YOU, BITCH.

She’s out for blood. Her way, in her voice. I love our similarities and differences. My mate Phil plugged into GPTchatbot: write a poem in the style of Selina Tusitala Marsh. It produced a lukewarm version of my voice. Then he asked it to write a poem mixing my style with Quentin Tarantino’s. It wouldn’t:

‘Marsh’s poetry style is known for its Pacific Islander culture and heritage, while Tarantino’s style is known for its violent and gritty themes. Combining these two styles in a poem would be incongruous and disrespectful to both the poet and the filmmaker.’

GPTchatbot obviously hasn’t read Avia yet.

Clarissa Pinkola Estes. Photo via breakingdownpatriachy.com

Most people know of Clarissa Pinkola Estes by her 1992 classic Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. Fewer, though, know about her 2011 publication The Dangerous Old Woman: Myths & Stories of the Wise Woman Archetype. As I enter into the Western medically defined period known as ‘perimenopause’ and what indigenous cultures elsewhere call all sorts of different kinds of rebirth, this book is a taonga. Full of story, ritual, ribald re-tellings of women and their relationship with their bodies, Estes’ global insights render one truth particularly vivid for me: western societies/patriarchal hegemonies/the whole shebang of capitalism teaches us to separate ourselves from the actual bodies we have. Estes showed me how to reconnect to the body Consort, our forever faithful companion until we die.

Ellie Brosh. Photo via https://www.facebook.com/GalleryBooks

I discovered Allie Brosh’s Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate situations, flawed coping mechanisms, mayhem, and other things that happened (2013) at the top of a pile of books in a corner of Auckland’s Hard To Find Book Shop. Actually, it found me. I’m working on my third graphic memoir in the Mophead series and Allie’s fresh, funny, vulnerable, truth-telling lines had me laughing and tearing up all day. Taken from her blog, these quirky tales of her life, often with her dysfunctional dogs, just warmed me and inspired me to be as true to the telling of my life as I can. Allie inspired me to muck around with a new series of cartoons that had me laughing out loud (see photo). Led by her line, I’m creating my own.

Paula Morris

When I was a student at the University of York in England, I studied fiction by American women writers for the first time – Kate Chopin, Eudora Welty, Paule Marshall, Toni Morrison. I started buying short story collections, and two writers became long-time obsessions: Deborah Eisenberg and Ellen Gilchrist. My introduction to Eisenberg was her first collection, Transactions in a Foreign Currency (1986), and Gilchrist’s second, Victory Over Japan (1984).

Deborah Eisenberg. Image via The Whiting Award. Photo credit: Diana Michener

Decades later, when I was living in New Orleans and teaching at Tulane, I got to meet both of them: I gushed to Eisenberg about her story ‘Window’ (from the collection Twilight of the Superheroes) and made her cry. Gilchrist visited one of my classes and we were all terrified of her. She invited me up to Fayetteville, to talk to her students at the University of Arkansas, and insist that I drink soup and Fiji water: I remained in awe. I wonder if my interest in New Orleans was a result of reading so much Gilchrist. Her story ‘Rich’, from In the Land of Dreamy Dreams (1981), remains one of her most famous, and might be the reason some people in the city shunned her work. It was a little too close to the truth.

Ellen Gilchrist. Photo credit: Nathalie Dubois

I came to Patricia Grace’s work relatively late – all her books read this century, I’m ashamed to say. Tu (2004) is an outstanding novel about the visceral experience of World War II and its consequences. Tu’s violent father is a destroyed veteran of the first war – ‘Just because he come home from war don’t mean he never died there,’ says Tu’s mother – but Tu can’t resist what he thinks will be ‘the biggest adventure’ of his life. This is an intense novel, exciting and moving, subversive in Grace’s particular way, and reminds us, on the 60th anniversary of Monte Cassino, how the fabled 28 (Māori) Battalion upended history, overseas and here.

Patricia Grace. Photo via the Arts Foundation

More recently, I’ve been reading a lot of Korean and Japanese fiction in translation – anything I can get my hands on. The opening sentence of Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami, published in English in 2020, reads: ‘If you want to know how poor somebody was growing up, ask them how many windows they had.’ After that, I couldn’t stop reading. Its subject is the perception and control of women’s bodies, and the novel is frank and unsentimental in its exploration of female relationships, motherhood and the constraints of class and social expectations in contemporary Japan.

Mieko Kawakami. Photo credit: Wakaba Noda

I will always love Gentleman Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos, published in 1925. The novel is written as a misspelled diary, recounting the misadventures in of avaricious ditz Lorelei Lee and her cynical friend Dorothy Shaw. On a trip to Europe, Lorelei is trying to ensnare the wealthy and pious Henry Spoffard, convincing him she is there to ‘improve’ her own mind and ‘reform’ Dorothy. In Munich, the girls suffer through a night of German theatre, then make separate plans for the day, as Lorelei notes:

Well today Mr Spoffard is going to take me around to all of the museums in Munchen, which are full of kunst, that I really ought to look at, but Dorothy said she had been punished for all of her sins last night, so now she is going to begin life all over again by going out with her German gentleman friend, who is going to take her to a house called the Half Brow house which is the worlds largest size of a Beer Hall. So Dorothy said I could be a high brow and get full of kunst, but she is satisfide to be a Half brow and get full of beer. But Dorothy will really never be full of anything else but unrefinement.

Anita Loos. Image via Silentlondon.co.uk. Photo credit: Cecil Beaton

Catherine Robertson

Last year, I found a four-volume collection of Mary Stewart novels in Book Hound in Newtown. The only title I recognised was Touch Not The Cat, which came out towards the end of her writing career in 1976. I had a feeling I’d loved it when young but could recall not one thing about the plot. Soon as I read the opening, where the heroine receives a psychic warning from her mystery lover, it all came back to me. Mary Stewart was my bridge from childhood fantasy novels to adult fiction that retained elements of the supernatural but added in romance that seemed quite raunchy to me in my early teens. Her books are action packed, the lead female characters capable, courageous and resourceful, as well as being excellent drivers who acquit themselves brilliantly in car chases. Stewart helped shaped my sense of what a novel should be, and I regret it’s taken me forty-plus years to reconnect with her.

Mary Stewart. Photo via The Scotsman. Photo credit: TSPL

I worship a long list of funny women writers but if I had to choose who’s had the most influence over how I view characters and language, it’d be Stella Gibbons. Her comic classic, Cold Comfort Farm was published in 1932 and has not been out of print since. It was meant to be a spoof of the earnest rustic novels popular at the time, but it’s much too rich and satisfying to be classified only as satire. The most famous character is, of course, Great Aunt Ada, who saw something nasty in the woodshed. But Gibbons gives everyone enough depth for us to care what happens to them. Even Great Aunt Ada, who is a tyrannical old bat. Gibbons’ dialect is comedy gold and her timing perfect. Witness this between farmer Reuben and lead character, Flora: ‘”I ha’ scranleted two hundred furrows come five o’clock down i’ the bute.” It was a difficult remark, Flora felt, to which to reply.’ Genius.

Stella Gibbons in 1955. Photo credit: Mark Gerson

It wasn’t until I read her recent memoir, From the Centre, that I fully appreciated how much Patricia Grace has meant to my reading and writing life. Her work has always been with me. Short stories in The Listener. The Kuia and the Spider/ Te Kuia me te Pungawerewere, a children’s book I loved even though I was in my mid-teens. Her novel Potiki that came out when I was 20 and caused a stir for its use of te reo with no glossary. (Thirty years later, my son would inform me that he felt no need to read another novel as nothing could ever be as great.) More short stories, Tu, Chappy. Her presence at writer’s festivals. Her wisdom, persistence and quiet steel. Her generosity and extraordinary legacy. Thank you, Patricia, for everything.

Patricia Grace. Image via www.neustadtprize.org. Photo credit: Shevaun Williams

Elizabeth Smither

Recently my daughter returned to me the Colettes I had given her as a teenager so they could be passed onto my granddaughter. They make a lovely line in the bookcase in their brightly covered Secker & Warburg translations. I open The Last of Chéri (1926) and locate the pages where Chéri discovers the courtesan, Lea, who had initiated him into the mysteries of sex has become ‘not monstrous but huge, and loaded with buttresses of fat in every part of her body. Her arms like rounded thighs, stood out from her hips on plump cushions of flesh just below her armpits. The plain skirt and the nondescript long jacket, opening on a linen blouse with a jabot, proclaimed that the wearer had abdicated, was no longer concerned to be a woman, and had acquired a kind of sexless dignity’. The Claudine novels – first published between 1900 and 1903 – will be where to begin, and the eternally loveable and precociously astute Gigi (1944).

Sidonie-Gabrielle Collette known as ‘Collette’. Image via Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Anne Kennedy’s The Last Days of the National Costume (2013) has always been a favourite. My sewing abilities are minimal – I remember cutting up one of my efforts from a dressmaking class and throwing it in the trash or labouring to the point of obsession on a quilt made from squares of evening dress. The garment in this case, around which the plot spins and flickers like a disco ball, is an Irish dancing dress which will require all the skills of Gogo the seamstress. Set in a period very similar to today – the Auckland blackout of 1998 – when the same inventiveness is required, as businesses operate by candlelight, valleys sink into shadows and GoGo restores more than a costume. How wonderful are all those Hi Vis wearers who can put things back together.

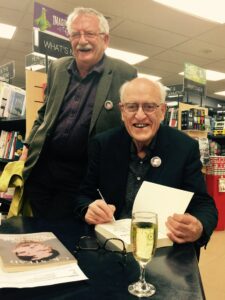

Anne Kennedy. Photo credit: Robert Cross, courtesy of AUP

The latest novel by Australian writer Gail Jones, Salonika Burning (2022), takes four famous figures – two Brits, two Aussies – who served in Salonika/Thessaloniki during the First World War and imagines how their stories might have overlapped. Salonika burns to the ground through mishap and the whole book feels like ashes and smoke. Miles Franklin, Olive King, Grace Pailthorpe and Stanley Spencer – identified as Stella, Olive, Grace and Stanley – are volunteers behind the front lines. Olive buys and equips her own ambulance, Stella is a nurse assistant, Grace is a surgeon and Stanley organises the donkey teams that act as stretcher carriers. The writing is episodic and impressionist – imagine a Seurat painting exploding and the pieces settling down, forever changed but utterly unforgettable.

Gail Jones. Image via The Saturday Paper, Aus. Photo credit: Eike Steinweg

Alison Wong

I think I was fourteen. In my hometown, now devastated by Cyclone Gabrielle, my English teacher Mr Exeter (Peter) lent me Janet Frame’s Owls Do Cry (1957). This was the first book to ‘explode its atoms’ of astonishment into my heart. I hadn’t known prose – a story – could be so poetic, that it could leap from possibility to possibility and be utterly, imaginatively transformative.

Janet Frame in the early 1960s. Photo credit: Jerry Bauer

Even so, as I scribbled my thoughts, my scraps of poems and stories, sometimes getting up in the night to write them down, I’d never met a writer, never even heard of a Chinese writer. I didn’t know I could be a writer.

Years later, on the footpath outside the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, I saw Patricia Grace. I knew she lived at the end of the road not far from where at dusk I’d walk along the beach bewitched by the wide orange-pink-gold sky, the dark silhouette of Mana Island. I‘d come to hear her speak. I was very shy, but she was alone, waiting, which made it a little easier to approach her. She did not know me, did not know if I had potential, yet this pioneer of Māori literature – author of Waiariki (1975), Potiki (1986), From the Centre: A Writer’s Life (2021), too many books to mention, literary mother to so many of us – told me in her quiet, steady voice, ‘You need to write about your people.’ Thank you, Patricia.

Cover image on Patricia Grace’s memoir From the Centre: A Writer’s Life (PRH)

Later still, someone gave me The Woman Warrior (1976) by Maxine Hong Kingston. This was the first book by a Chinese writer that thrilled me with its poetic landscape of dream, memory, myth. A generation older than me, she is American with immigrant parents, her experience and stories are very different from mine, more fantastical, more ‘Chinese’. Yet here at last was a Chinese writer who opened the windows of my imagination. Now I read again the first sentence on the yellowed first page: ‘You must not tell anyone,’ my mother said, ‘what I am about to tell you.’ I laugh. I am writing my own memoir. I wonder if I am an obedient daughter.

Maxine Hong Kingston in 2017. Image via The Chronicle. Photo credit: Lacy Atkins

After so long almost alone in the desert of Asian literature of Aotearoa, just the odd precious book/author springing up here, there, now I witness a burgeoning of voices. Now one of the books that speaks of my astonishment, my joy, is A Clear Dawn: New Asian Voices from Aotearoa New Zealand (2021). The writers and works within this anthology are only an indication of the vibrancy and diversity of not just Asian voices, but of all New Zealanders and our complex, evolving, multiple identities, languages and cultures.

Briar Wood

Books by women writers have inspired me since before a time I can remember consciously. My early reading was filled with popular texts by widely respected authors. Sadly, books by writers from Aotearoa New Zealand were not so accessible then as they are now. I liked school journals a lot, and at some point early on, read a memorable story by Arapera Blank, although I didn’t know it was by her until rereading it many years later.

Arapera Blank. Image via Spiral Collectives

The first classics I read, or tried to, aged around nine or ten, were Wuthering Heights, which I got drawn into immediately, and Jane Eyre. The latter was a puzzle until later, although the chapter with the death of Jane’s friend Helen Burns at boarding school made a big impact because my Mum had been to girls’ boarding school and was a nurse.

Dorothy Parker’s pithy wit had an impact on me as a teen reader. Romance between women and narratives of female friendship (Alice Walker’s The Colour Purple) made strong impressions, as did the work of poets like Gwendolyn Brooks, Adrienne Rich, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and Denise Levertov. American poetry was influential at the time I was studying at university, often foregrounding open form and colloquial language. I grew up trying to practice ecologically aware economy, and poetry seemed the form that most fitted that worldview. Sci-fi by women also fascinated me at that time; I reread Octavia Butler’s Parable books not long ago and still can’t put them down.

Gwendolyn Brooks on the front porch of her home in Chicago. Photo credit: Art Shay

Fleur Adcock wrote poetry that briskly moved relationships between Britain and Aotearoa into modern times. My mother died recently and recalling Adcock’s poem ‘The Chiffonier’ with its cry of middle-class angst ‘I want my Mother, not her chiffonier’ was strangely comforting. Yes, however we might surround ourselves with home comforts, relationships with loved ones are primal. She refers to her mother as ‘Dear little Mother’ like a character from a play written in Soviet realist style, and it’s that sense of the mother as a person who is both individual and like someone from a folk tale or pakiwaitara that I find so deeply tender and affecting. A woman friend confirmed that she too remembered the poem from the 1980s when it was first published in The Listener.

Fleur Adcock. Image via Owlcation.com

Interesting then, that the two books I think about the most in contemporary times are novels: Patricia Grace’s Pōtiki and Louise Erdrich’s The Night Watchman. The integral connections of people to whenua and moana in Pōtiki and how whānau pull together to hold onto their marae are a life-lesson. Grace’s use of multiple narration gives the novel so many facets that it’s an iridescent ao, hurihanga. My students in London got it, loved it. It’s as relevant now as it was when it was published in 1986. I’ve truly read it dozens of times and always learn something new. The book shows the benefits of marae existence, so that all readers can appreciate the necessity of maintaining connections to customary ways of life.

Erdrich’s The Night Watchman is a classic page turner. The characters are utterly spellbinding, the young women finding jobs in the 1950s, dating, sharing their lives with each other and meaningful exchanges in the car on the way to work, confused and focused young men, fathers, mothers, grandparents, whānau. Perhaps because it celebrates the history, humour, ways of life and survival of Chippewa people I would know little about without it, if I had to take one book with me for a long journey anywhere, this is the one.

Louise Erdrich. Image via The Dartmouth News. Photo credit: Joseph Mehling