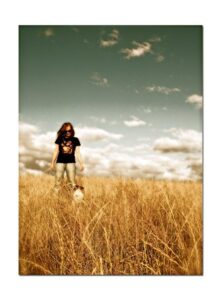

Kelly Ana Morey: 1968–2025

.

‘I’ve always been the pain in the ass who wanted to row her own waka in her own way.’

– Kelly Ana Morey

By Paula Morris

Kelly Ana Morey (Ngāti Kurī, Te Rarawa, Te Aupōuri), who died on Monday 1 September aged 57, was many things. Her friend Catherine Chidgey describes her as ‘novelist, historian, photographer, reviewer, and one of the hardest workers I’ve ever known.’ I’d add art writer, stylist, collector, fashion insider, aesthete, gardener, truth-teller, hard case and self-described ‘shit hot waitress’. In her misspent youth she was a denizen of Auckland’s nightlife, a beauty-about-town – after a childhood and adolescence moving between New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, always reading. ‘She was a considerable writer,’ says Elizabeth Aitken-Rose of the Sargeson Trust ‘and, more than this, a fierce, intelligent and enduring contributor to Aotearoa’s evolving cultural life.’

On her Facebook page KAM described herself a different way: ‘Half-assed novelist, animal hoarder and arsonist’. ‘I’ve never really been a joiner,’ she once told scholar Ann Pistacchi. ‘I’ve always known exactly who I am … hard to miss when all your Kaitaia relations are brown as, but I’ve always been the pain in the ass who wanted to row her own waka in her own way.’

.

KAM and I met in Wellington in 2001, when both of us were finalists in what is now known as the Pikihuia Awards; our stories were published in a Huia anthology, and I took part in a public reading with KAM and fellow finalist James George. Both KAM and James made themselves cry during their readings and I wondered if this was normal. I returned to the U.S. and we didn’t meet each other again until 2005, at a book launch on Karangahape Road for my second novel, Hibiscus Coast. By then she was publishing abundantly imaginative novels with Penguin, and she seemed sparkling and lively – my kind of writer friend.

When her debut novel, Bloom, won the Hubert Church Award in 2004, KAM was only the fourth Māori – in almost 50 years of the prize – to win, following David Ballantyne (1949), Alan Duff (1991), and me (2003). She’d already been awarded the Todd Young Writers’ Bursary. Her second novel, Grace is Gone, was shortlisted for the international Kiriyama Prize; in the same year, 2005, she won the inaugural Janet Frame Literary Trust Award. In 2014 she was awarded the Māori Writer’s Residency at the Michael King Writers’ Centre. There would be another three novels: On an Island, with Consequences Dire (Penguin 2007), Quinine (Huia 2010) and Daylight Second (HarperCollins 2017), as well as social histories, stories, poems and a childhood memoir – of sorts – called How to Read a Book (Awa Press 2005). She was working on another novel – finished? Almost finished? – when she died.

Like so many writers in New Zealand, KAM had to divide her time to make fiction-writing possible: there were always bills to pay, animals to feed, an old house north of Auckland to fix and renovate. In op-ed for Stuff written in 2017, she described applying for a WINZ benefit two years earlier. ‘Given that I’ve chosen to live rurally and earn a living as a writer/waitress, my financial life could charitably be described as precarious,’ she wrote. ‘Generally I make it – something nearly always seems to come along in the nick of time. But sometimes the wheels can and do fall off my little sideshow.’ Sometimes it was too much. ‘I plant trees, dig drains, feed the animals and shiver as I do my fifth winter without heat,’ she wrote in 2017. ‘And I feel old and broken.’

.

Financial need meant she had to take on numerous nonfiction commissions and jobs as an oral historian. In April 2016, she emailed me to say she was ‘at home all week alternating between writing a concise yet entertaining summation of Bay of Islands Maori politics circa 1800 and editing the novel. Yay for editing the novel. I’m tired of the sight of the wretched thing.’ (The novel was Daylight Second, which she was still calling ‘Phar Lap’.) KAM ‘had the rare gift of making art while also juggling the sheer hard graft of making a living,’ says Chidgey, ‘and she never stopped creating’.

*

KAM was born in Kaitaia in 1968. Her mother was from Rotorua and of French/German heritage; she had, KAM told scholar Ann Pistacchi, ‘the most magnificent beehive’. Her father was the descendant of a Jewish trader who set up a general store in the Far North and a high-ranking Ngāti Kurī woman. Both parents were talkers and ‘voracious readers’, she recalled in How to Read a Book. But KAM absorbed her ‘mother’s trenchant unhappiness … in a location she never learned to love’. After years in the New Zealand Navy, her father became a shepherd in the Hokianga and then a surveyor, among other things.

The family moved to Papua New Guinea in 1971, where her father worked in various jobs and the family kept moving. It was, she told Pistacchi, ‘the most fabulous childhood. It was quite solitary and in many ways I think a perfect training ground for being a novelist because it taught me to be really happy with only my imagination to keep company with.’ Her mother encouraged her writing and both parents supplied her with books, though these weren’t always easy to find – embracing her identity as a ‘book-worm’ so they could ‘explain my (even then) pronounced singularity,’ she wrote in How to Read a Book. ‘I was not a “friends” kind of child.’ She was happiest with books, dogs and horses, as she would be all her life. She drew on the landscapes and history of Papua New Guinea for her fourth novel, Quinine.

At the age of 12 KAM was sent back to New Zealand to board at New Plymouth Girls’ High School. She preferred the heat and magic of Papua New Guinea and spent her five years at school ‘doing nothing very much in particular,’ she told Pistacchi. Her talent recognised by teachers, she was invited to take part in a special creative writing workshop run by David Hill. Other girls were drawn to her charisma. Auckland writer Karen Holdom arrived at the school in the sixth form and was delighted to be drawn into KAM’s circle.

She wasn’t one of the popular girls, the surfy, outdoors, ponytailed lovelies. Those girls couldn’t see what we could, which is that Kelly was the wittiest in the room, the prettiest, the smartest, and the bendiest (her legs and arms folded in impossible knots, those long, bent-back fingers begging a cigarette). She could keep a secret – and did. She was a bit goth, a bit rebellious, but also studious because she couldn’t help herself. She sported with the teachers, and the good ones didn’t mind. My sixteen-year-old self wrote to an expelled fellow student to say life without her would be like haybarns without sex, mountains without Yetis and ‘biology without Kelly Morey.’ The world was just more interesting with her in it.

.

.

KAM repeated her sixth-form year then left for university in Auckland. In a 2022 essay for Reading Room, she described herself as ‘a provincial goth with the requisite spiky bleached blonde hair, heavy make-up, layers of black rags and all-important faux existential ennui’. Her stint in student halls was short – ‘I was a smoker who kept unsociable hours and dubious company’ – and she spent more time working in clubs and restaurants than studying. After ten years of part-time pursuit of a degree in English and Art History, KAM decided to commit. In 1997, Witi Ihimaera and Albert Wendt accepted her into their creative writing class, and her story ‘Māori Bread’ was accepted for publication in the anthology 100 New Zealand Short Short Stories (Tandem). By the time I met her in 2001, she had completed an MA in Art History and was hard at work on Bloom.

.

.

.

For KAM, Auckland was a glamorous interlude. In her 30s now, joking that she was over-educated and unemployable, KAM returned to the north, and to the countryside. When Ann Pistacchi was writing her doctoral thesis, Morey’s writing career was in its early years but apparently embedded in the north. She talked to Pistacchi about how she liked to ‘write rural communities’ and Pistacchi declared that KAM was ‘anything but an urban dweller. While aspects of her narratives include recognition of violence, poverty, dislocation, and Māori activism, her novels have a decidedly non-urban spirit.’

Certainly, KAM loved her life in the country. She and Catherine Chidgey ‘compared notes on living with messy, sometimes destructive pets’ and Chidgey says she ‘was always moved by the deep love she showed her animals – her horses, hounds and cats.’ KAM considered becoming the Māori rep on the NZSA board but said ‘the travelling ruins it for me’. She preferred to stay at home but in the loop at the same time. Once when I asked her to do something she agreed because ‘my life is a bit slow at the moment as I’m just pottering around at home being a lady novelist’. Another time she agreed because ‘I’m not doing much more than hiding at home and writing ’.

.

……. .

.

……………..A few of KAM’s beloved ‘critters’. Photo credit: Kelly Ana Morey.

.

In their introduction to the anthology Black Marks on the White Page, Witi Ihimaera and Tina Makereti talked about KAM’s story as an example of ‘radical ordinariness’, a way of presenting ‘the lives of ordinary people’ and ‘at the same time challenging our understandings about the way things are.’

But she was equally home in the supernatural or mythic. For the 2019 anthology Pūrākau, edited by Ihimaera and Whiti Hereaka, KAM wrote a story called ‘Blind’, imagining the ogress Rūruhi-Kerepō as an inmate of Kingseat mental asylum. The subject, KAM wrote, ‘was the obvious choice for me really.’

.

Evil old child-eater! How could I resist? But there were other reasons why I chose her, the main one being there was pretty much nothing written about her so that gave me the opportunity to take her anywhere I wanted, so I did. I also loved that her name translates as ‘old Woman’ and that got me thinking about hierarchies and how to be old, brown and a woman is to have no value.

.

As the years between novels stretched, she would think more and more about this. KAM was frank about her prevailing moods; she was given to love-hate relationships. She spent so much time alone that existential crises could settle in her house and in her mind. Sometimes she relished her outsider status. ‘There’s a reason why I’m a writer who doesn’t do the networking thing,’ she told Karen Holdom in 2020. ‘I am simply better by myself, the lit world does my head in’. (Later she told Karen, ‘I get more satisfaction doing beautiful gardens and houses and riding my horse’.) Many of her friendships were conducted virtually. ‘For 15 years we chatted online,’ says Chidgey, ‘a constant thread of conversation that wove through my life. We swapped recommendations for books, good TV and bad TV, interior decorating with antique treasures found on Trade Me or at auction houses.’

Some of KAM’s home treasures, including the green wall she often used for a backdrop to photograph her decor collections.

.

At other times this isolation led to bitterness and paranoia. KAM could lash out even at friends and supporters, especially when she was feeling professionally or personally overlooked. I’ve been on the receiving end of various lashings. In 2018 a Creative NZ delegation of writers was sent to London to participate in events around the Oceania exhibition at the Royal Academy. The writers were me, Witi Ihimaera, Tina Makereti, Karlo Mila and David Eggleton. KAM was furious that she hadn’t been invited – as an art historian as well as a writer – and vented in public mode on Facebook. I asked her to stop and said it was distressing to read the pile-ons from her followers. ‘Welcome to my world,’ she said.

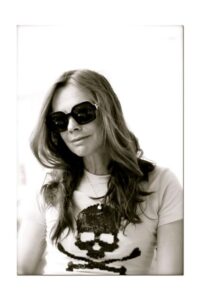

But the storm always passed with us – or, at least, the whip was set aside for a while – because our issues weren’t personal. We liked each other, and we liked to moan to each other about the writing world, the writing life, the writing. We also relied on each other: I commissioned her to write book reviews and to serve as external examiner for some of my Master of Creative Writing students at the University of Auckland. She almost always said yes, in part because it suggested her judgement was valued. In 2016, when Harley and I were getting the Academy of New Zealand Literature up and running, KAM was a supporter and contributor, writing the ‘appreciation’ for Keri Hulme, interviewing Fiona Kidman and supplying a superb portfolio of photographs for us to use with features and essays.

.

Above, a selection from Kelly Ana Morey’s portfolio.

.

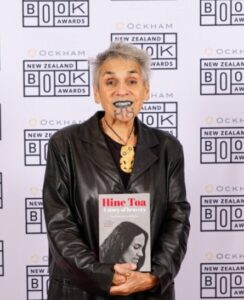

In 2021, when I asked her to be a fiction judge at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, she agreed at once: ‘I think it’s time to stand up and be counted.’ I really liked that about her. In a country where too many book reviewers will tell you, in private, what they really think, she would write what she thought. ‘Well this isn’t going to make me any friends,’ she told me, submitting review copy for a book by a popular writer. When a publisher had neglected to send her a book, she wrote: ‘Maybe they fear me’.

Also, she always needed money. When I asked her to examine another piece of gloomy realism, she wrote: ‘I’d give a three legged cat for something funny. Sadly I have to pay the last bit of said cat’s horrendous vet bill, so I’ll say yes.’ (‘I tell people, say what you like about Paula,’ she told me once, ‘but she always pays on time’. This was untrue: often I don’t pay on time. Also, I hadn’t realised ‘people’ were nasty about me. Welcome to my world.)

Like all friends and writers, we had in-jokes, and we sometimes complained about each other. In 2019, she told a mutual friend that ‘your friend St Paula takes all the Māori money’. This had been a running joke between me and KAM for years, dating back to some parody CNZ letters I wrote in the personae of other writers. (‘Please send me all the Māori money.’) But she emailed me when my father died, and when I was getting abuse from someone, she wrote: ‘Jesus what the hell is wrong with people.’ Once she told me that some writers couldn’t ‘take ‘KAM’s brutal truth’, and that became one of our favourite lines.

We also emailed and commiserated about the expectations and demands made of Māori fiction writers. Everyone should read her Spinoff essay from 2017, written not long after her own father died, about being ‘a Māori. In my own funny way.’ It examines KAM’s feeling of isolation within the prevailing Māori narratives. ‘I can’t be the “Māori” writer people want me to be,’ she wrote; ‘all I can be is myself. Mining the Māori world for material would somehow feel like an act of theft because my knowledge and connection feel so slight and arbitrary.

This is why I don’t write from the Māori perspective all that often in my fiction, and if I do those characters tend to be quarter-cast who are like me a little disconnected. They operate as individuals rather than cultural representatives. There are no marae visits or lovingly written tangi in my New Zealand novels. There’s the odd visitation from a ghost or two but every culture has that going on. And the narratives are concerned with the here and now of surviving and knowing who you are and being okay with that. The complicated world of identity and authenticity which challenges those of us who are neither one nor the other. So I shuffle between my realms, the problem child no one really wants.

That sense of herself as ‘problem child’ extended to our small literary world. Relationships with publishers were not always good; KAM often felt unsupported and ‘silenced’. She took rejections badly, writing in 2017 that she’d ‘written countless futile Creative New Zealand and writers’ residency applications’. That year, joining Auckland Museum’s oral history team and offered a writing contract by another museum, she wrote: ‘So after six years in the wilderness I’m back on track. See if Waikato Uni had given me their residency instead of my fifth rejection from them, none of this would have happened. Well done cow college.’ It took many, many applications to get the Sargeson Fellowship, in part because KAM would announce that she just wanted the money, not use of the writing residency on Albert Park. (She was awarded the residency – at last – in 2023.) Even when she got grants, she could complain. ‘I’ve only just got myself back into CNZ good books,’ she told me in 2015. There ‘have been far too many times in the last 6 years when it’s been a bit like the siege of Leningrad for me to shut the hell up and take my hush money’.

.

For someone so prickly, KAM was amenable about being edited, whether I was re-structuring a review or giving feedback on the fiction she submitted for inclusion in my anthology Hiwa: Contemporary Māori Short Stories. But she could drive me crazy. Each year the ANZL sends an ‘author showcase’ to hundreds of festival directors around the world, looking for international opportunities for New Zealand writers. After Daylight Second was published, a festival expressed interest in KAM. ‘Durban hosts the biggest horse race in South Africa,’ I wrote to her. They would pay for her airfare and hotel and give her a meal allowance. She made plans. ‘I have a week off work and critter sitter jacked up … now all I need is some anxiety meds, a passport and one more animal put to death’. I confirmed with the festival. And then she cancelled, saying ‘my spooky old lady skills aren’t happy about this one’.

But she was, as Chidgey says, ‘the one and only Kelly Ana Morey’ – funny, frustrating, smart and smarting. ‘Kelly was devoted to writing even though she knew it wasn’t good for her,’ says Steve Braunias, a long-time friend and admirer of her work. ‘There were a lot of disappointments and setbacks and general punishments, but she kept coming back for more.’ She could be angry or sad, but she was not deterred. KAM ‘needed to write,’ she wrote in the Spinoff, ‘because aside from thinking deep thoughts and waitressing, I’m not terrible good at anything else’. She also enjoyed making trouble: ‘I’m off to poke some tigers with a stick’.

.

As well as career setbacks, KAM suffered from ongoing physical pain. We asked each other a lot about health issues, but mine were just injuries and surgeries. KAM had Crohn’s Disease, and what she once told me was three decades of a ‘constant low grade chronic gut pain’. In passing she would mention ‘my last bowel resection’, but the most important thing was to get ‘back on a horse six weeks after’ and be able to work in her garden. She couldn’t come to the launch of Hiwa in 2023 because apart ‘from being a hermit I have the Covid. Fark. It’s been awful. Even getting dressed is a mission.’ This July she told me she’d been ‘battling influenza’ for a month.

On 19 August, she emailed me from Whangarei Hospital to say she was in intensive care; this meant she couldn’t get a book review finished. I asked her if she needed anything and she asked: ‘Can you post me some lollies. I’m desperate for snacks’. My old school friend Sally Wilkinson, who lives in Waipu, drove up two days later with the requested wine gums, jellies and M&Ms. ‘The absolute joy of lollies,’ KAM wrote. ‘Thank you so much for the lolly fairy.’

A week later:

KAM: On my way home this afternoon. feel better than i have done for months.

Me: I hope you have more energy, you poor thing!

KAM: I still have a way to go yet. I could probably get that book reviewed for you.

Me: Only when you feel up to it. There is a contract for you to sign as well, perhaps?

KAM: Oh yes and I need to confirm my bank account.

That was our final exchange. ‘Brave little Kelly walked a hard road,’ Braunias says. ‘New Zealand literature was the better for it. I will miss her very much.’ Chidgey says: ‘KAM’s extraordinary novels leave a legacy that speaks to her rich imagination and her tireless dedication to storytelling; her non-fiction projects show the same intelligence and commitment to the written word. I will so miss her conversation, her support and her friendship.’

I will miss her wit and her brutal truth. Two years ago, she told me: ‘I’ve counted up my lives and KAM the cat has four more left’. None of us thought those lives would be used up so soon. ‘The fires will continue to smoulder with or without me,’ she wrote in the Spinoff in 2017, calling out to ‘a group of incredibly well-educated, talented Māori women storytellers who take no prisoners and offer no apology for who they are and what and how they write’.

We will keep the fires going, KAM.

Links to KAM reviews on the Aotearoa Review of Books:

21 May 2025: Tina Makereti: This Compulsion In Us

11 April 2025: Whiti Hereaka and Peata Larkin: You Are Here

8 November 2024: Monty Soutar: Kāwai: Tree of Nourishment

6 September 2024: Kirsty Baker: Sight Lines

3 April 2024: Lauren Keenan: The Space Between

18 August 2023: Airana Ngarewa: The Bone Tree

.

'The thirty-five of us were in the country of dream-merchants, and strange things were bound to happen.' - Anne Kennedy