Writers’ Round Table on Japan

A Taste of Clouds: New Zealand Writers Encounter Japan is a free ANZL bilingual sampler created in 2022 and available for download here.

The New Zealand writers sampled in this publication have all encountered Japan — in real life, on the news, through relatives and ancestors and friends, or in their imaginations. A Taste of Clouds features excerpts from creative work by Johanna Aitchison, John Tāne Christeller, Patricia Grace, Siobhan Harvey, Kirsten Le Harivel, Jeffrey Paparoa Holman, Ben Kemp, Colleen Maria Lenihan, Vivienne Plumb, Yeonghee Seo, Kerrin P. Sharpe, Carl Shuker and Yoshiko Teraoka.

This round table brings together Kirsten, author of the poetry collection Shelter (2021), who lives on the Kāpiti Coast; Colleen, author of the story collection Kōhine (2022), in Auckland; Carl, author of five novels, in Wellington; and Yuten Sawanishi, a fiction writer and lecturer in Japanese literature, in Kyoto. Paula Morris – project manager of A Taste of Clouds – asks questions and mentions Korea.

Yuten is on the board of the Kyoto Writers Residency, launched in October 2022: Paula took part in the inaugural residency, and the photos of Kyoto in this feature are from her time there. The other writers in the 2022 residency were Hubert Antoine, Ao Omae, Emily Balistieri, Alfian Bin Sa’at and Anna Cima.

Our conversation took place in February 2023, prior to Yuten’s first visit to New Zealand to explore possibilities of a reciprocal writers’ exchange.

Paula: Would each New Zealander talk about the time you spent in Japan and which of your works are set in Japan? You could also mention other places you’ve lived. Yuten, could you tell us a little about your own work, and also about the time you spent living in Germany?

Colleen: I first went to Tokyo in 1999 for a three-month stint. Upon my brief return to New Zealand, I accepted a marriage proposal from my Japanese boyfriend over the phone, and moved there in a matter of weeks. At first I lived in Fuchu, a city in the Western Tokyo metropolis, then moved to central Tokyo: Shibuya, Daikanyama and Roppongi. On that initial trip to Japan I worked in the mizu shobai as a dancer in Kabukicho, Tokyo’s red light district. It was an incredibly stressful job and my first time overseas. I felt like a baby – everything was new and I didn’t understand anything. It was all very overwhelming and I vowed never to return.

But back in New Zealand, the pace of life was so glacial after the intense energy of Tokyo and I couldn’t stand it. I was in love and desperate to go back. Tokyo is so fascinating, thrilling, and addictive. I felt like I was in a movie. I hung out with strippers, models, money brokers, DJs, rock stars and yakuza. l stayed until 2014, and moved to New York for about 18 months. I much preferred Tokyo though and never really settled in New York. I came back to New Zealand in 2016 and started writing.

In my short story collection Kōhine , nine of the stories are set in Japan and draw on my experiences there. Losing my only child in Tokyo, working as a dancer and a hostess. The story ‘Directions’ is told from the point of view of crows living in Daikanyama. I was obsessed with the crows and often photographed them. They are a constant, watchful presence and quite intimidating. They cause problems as they dig through trash, lay stones on train lines and sometimes attack people. I was intrigued to learn that in Japanese mythology they are divine messengers and a symbol of power. They are magnificent, clever birds.

Yuten: Nice to meet you all online. I’m Yuten Sawanishi, a novelist. You can read one of my stories in English – ‘Filling up with Sugar’– on the Granta site. It is also included in The Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories. I have not yet written a novel set in New Zealand, but I have written a novel set in a deserted island in Polynesia. The title is Rain and Crows. It’s a story about a World War II soldier and an army nurse who survive on a deserted island and have children. It’s about their grandchildren as well. The story begins with the last survivor, Tadashi, found in a Harakiri state, and then their family story is told from Tadashi’s perspective.

Colleen brought up the topic of crows: although crows are not supposed to be in Polynesia, they play a very important role in my novel as well. However, this is not based on a Japanese myth, but on an image of the raven as the god of creation.

Until I was six and a half, I lived in Germany because of my father’s job. When I played with my brother and friends, I spoke German and I used Japanese only when I was talking to my parents, so when I returned to Japan and entered elementary school, I was shocked to find that I could not understand what the people around me were saying. I could also hardly read or write, so Japanese appeared almost as a foreign language to me, not my mother tongue. I remember I was crying on the way home on my first day of school.

I picked up the Japanese language quickly, but even now, as a writer, I still find the Japanese language to be restrictive. On the other hand, Germany is not my home ground either. When I was a university student, I went to Germany for a short-term study abroad (I’d forgotten my German, so I studied it again from scratch). At that time, I realised that wherever I went, I was myself, and decided to do what I wanted to do. So I decided to become a writer.

Kirsten: I arrived in Tokyo in my mid-twenties with the intention of cycling from Japan to Europe with a friend. However, not long after I landed I was drawn into a spiritual eco-commune in the foothills of Mt Fuji, which turned the cycle tour upside down. Eventually I got back on my bike and we cycled around Hokkaido but that was where my tour ended!

When my visa ran out, I sent the bike back to Aotearoa and went on to study meditation in Thailand. I continued west, to India, to visit a family I met in the Japanese commune, and worked in their hometown, Ahmedabad for three years. The city had a thriving network of social organisations (a world I was familiar with in New Zealand) and I was lucky to work for two local NGOs, the first supporting young Indian graduates to create social change and the second, an ethical travel guide in the style of Lonely Planet but developed by Gujaratis.

Several poems in my first collection, Shelter, are set in Japan, some of which are included in A Taste of Clouds, and aspects of my time there continue to feature in my work. Japan was where I picked up a pen for the first time since my teens and when I returned to New Zealand, I was committed to being a writer, although it took me a while to call myself one.

I understand Yuten’s feeling of disconnection: I grew up in central Glasgow, moved to rural Palmerston North as a teenager and then lived for several years in Asia, before returning to New Zealand. For a long time, I felt like a real outsider here too. Migration, home, belonging are all themes that seem to come up in my work – how we connect (or disconnect) from the places and people we come from and how we find ourselves in the places we have come to.

Carl: Wow, what an amazing set of stories: Japan really was and clearly is a locus for fascinating personalities. I overlapped with some of you in weird ways – I came to Tokyo in ‘99 too, Colleen! But age 24 with debts and needs for money and experience after finishing my first novel and wanting adventure. I returned to NZ to write up this experience in a book about gaijin decadence in Tokyo and Japanese history called The Method Actors, then 200,000 words wasn’t enough and I had to go back.

The second trip I feel I may well have visited and stayed at that eco-commune near Mt Fuji, Kirsten! Couldn’t be the Earth Embassy/Solar Cafe place here could it? The place made a big impression on me. The floating forest of Aokigahara is one of those intense places with physical-spiritual loads like Jerusalem, Beirut, Nagasaki, Shimabara… I set part of Three Novellas for a Novel at the commune’s cafe/inn: I did a limited edition download ‘for free or more’ of the book for a while which you can still find on the wayback machine. Some cool photography from Japan courtesy of a friend and colleague there. The book imagines a future of concrete cancer where Japanese cement buildings can suddenly collapse, so an architecture of wood and plexiglass is growing.

Yuten, I’ve met many very interesting Japanese who find themselves caught somewhere between the world of other countries and never quite back inside traditional Japanese life and expectations. In my experience these people suffer somewhat for it, but become very interesting individuals. Japan’s closedness – 250 years of isolation, and intense immigration policies since – is a feature of the experience. Sometimes I never felt so free, others never so boxed in. I had to leave as I saw myself becoming shut in a gilded cage, but it has driven me to two books and a lifelong love-hate relationship with the place, not to mention the immensely important cuisine.

Carl in Shibuya, Tokyo, 2001 Mt Fuji. Photo credit: Anna Cima

Paula: Carl talks about a love-hate relationship with Japan. I wonder if we all have that with anywhere we live, as well as the place we come from.

Colleen: Great question! But first, Kia ora, Yuten – I enjoyed your short story on the Granta site and I’m intrigued by the premise of your novel, Rain and Crows. Sounds right in my wheelhouse! And ngā mihi to you all for sharing your experiences. I read them avidly and could empathise with a lot of things – as in Kirsten’s work, themes of the notion of home, and where is home anyway, emerge in my own writing. In my story ‘Mama’, the hostess protagonist is weaving through Ginza alleyways when it hits her: ‘How did she end up here? When she first arrived in Tokyo, everything was weird. Then it became normal. Now it was weird that it was normal.’

I absolutely love Japan and have a deep respect and admiration for the Japanese people and culture. Though as I mentioned, I struggled there, even hated it, at first. I recall catching packed trains all over Tokyo, commuting from various teaching jobs, and would be out in some suburb on the outskirts of the city in a sea of people and be the only foreigner. Everyone in my world for prolonged periods was Japanese, aside from my daughter. I was definitely an outsider. Gaijin literally means ‘outside person.’

It was hard on my daughter too. I was once summoned to her high school, to be confronted by the principal and all her teachers looking very serious. I didn’t know what had happened, Monique was clearly upset and I was alarmed. What kind of trouble was she in? The principal said that my daughter’s hair was the wrong colour and unfair to the other students, who weren’t allowed to dye their hair. She solemnly pushed a box of black hair dye across her desk and all the teachers agreed – this was the solution. I explained that dark brown was Monique’s natural hair colour, and pushed the box back. That wouldn’t do, and the box was presented to me again. We never did dye her hair black.

My daughter made a lot of friends, and had many caring teachers over the years. Her first elementary school in Japan assigned Monique her own teacher to learn Japanese one-on-one, and she was fluent within six months. They were very kind to her and I, and did their best to make us feel welcome and included.

I miss Japan but haven’t returned since I left nine years ago. I can’t wait to go back. Having spent most of my adult life there, it feels like my second home. Returning to New Zealand was rocky as I had reverse culture shock. For a while, I felt people here were quite rude because I was used to Japanese manners. It took me five years to settle. I love Aotearoa; this is my tūrangawaewae. But even now I still find some aspects of the culture challenging. I miss Japanese customs and ideas about the world. Sometimes, when people complain, I want to say ‘Shouganai’ [‘It can’t be helped.’]

Kirsten: It’s so really fascinating how many crossovers there are between us all, I love hearing everyone’s stories. I wonder if this feeling of ‘love-hate’ is almost an inevitable part of the experience of being a migrant and/or from a migrant family (or from a minority group in society), because we have this knowing that our familial way of life, isn’t the only way to be and that it can sometimes be antithetical to the values of the society we’re living in.

Like Colleen, I find there are aspects of each place I’ve lived that I cherish and ones that I am quite happy to have left behind. I also felt reverse culture shock when I moved back to New Zealand after living in India and if I’d had an equivalent of ‘Shouganai,’ I would have used it! I found the lack of information and awareness of the world outside of Aotearoa and—amongst middle-class-plus peeps particularly – the lack of awareness of privilege, inequality and the patriarchy really rattling. It took me several years to feel ‘at home’ here again as I didn’t feel that I fitted into the expected Pākehā, white, middle-class boxes, though I benefit from them, because of the way our society operates.

I also experienced some of the isolation and loneliness that can come from being the only foreigner at work, home and in the community. Sometimes, I also found it kind of freeing – something I only realised when I came back to Aotearoa and all the ‘noise’ and expectations from media, government, socials and corporations was suddenly directed at me. I realise that being able to operate safely in any society is a situation of immense privilege.

Had my background been different and my then in-laws and friends imposed more of the localised expectations on my behaviour, I would most likely have had a different experience. At that time, I was also really committed to assimilating. Now that I have kids, I know I would have been a lot less willing to take on values that didn’t align with my own.

Yuten: There are so many common topics and things I don’t know that it’s exciting for me too. Kirsten and Carl, I didn’t know there was such a spot on Mt.Fuji. I haven’t climbed Mt.Fuji yet, but now I have a place to stop before I reach the summit. Colleen, thank you for reading my work. Your story about your daughter’s school reminds me of my experience at swimming school when I was in elementary school.

I went to swimming school with my brother. When I was in Germany, I learned breaststroke first, in case I drowned in a river or the sea. For the same reason, I experienced swimming with clothes on. But in Japan, we learn crawl [freestyle] first. I don’t know why. The swimming school had a designated swimsuit made and sold by the school. One day my mother gave us each another swimsuit because the designated one hadn’t dried after the wash. When my brother and I were about to enter the pool wearing these swimsuits, the coach stopped us. We weren’t allowed in the pool because we weren’t wearing the school swimsuits.

Afterwards, the school called my mother and had her bring our school-specified swimsuit. Meanwhile we were standing at the edge of the pool. My mother was very angry. ‘Why can’t my children enter the pool just because their swimsuits are different?’ she asked. The coach said, ‘Your children are so embarrassed. It’s a pity.’ ‘It’s your fault,’ my mother retorted. My mother (especially after returning from Germany) is a person who speaks her own thoughts to everyone, as Carl said.

Now I know that my mother was right. But then I was really embarrassed. At the age of eight, I was trying very hard to fit in as quickly as possible. I was good at breaststroke and loved swimming, but in Japan I started as a beginner. At the same time, I was tired and hurt by the act of worrying about my surroundings. In this country, fitting into a group was an important way of life.

On the other hand, within the rules, if you show that you are excellent, you will be praised. The swimming cap has a place where a magic sticker is attached, and each time the swimming technique improves, the line increases one by one and the colour changes. Beginners have a white line up to three lines, then intermediate has a red line, advanced has a blue line, and masters have a black line. Aiming for each higher class, students master swimming. Such a kind of system tames children through rules. I think that there were a lot of small traps like that in Japan, and the mindset of ‘Shouganai’ was nurtured in this way.

Kirsten’s words recall something Paula and the Belgian writer Hubert Antoine said at an event during last year’s Kyoto Literary Residency. Japanese people are very kind; if you ask for directions, they will show you the way; if you ask how to send an email, they will help you. However, there are few people who really care about the other person and follow through to the end in any situation. They check the rules, but if you’re not following the rulebook, they often won’t help you further. In the past, it was said that everyone was not kind in the way they are today in Japan. Instead, there were ‘really kind people’. Recently, I feel that the number of genuinely kind people has decreased.

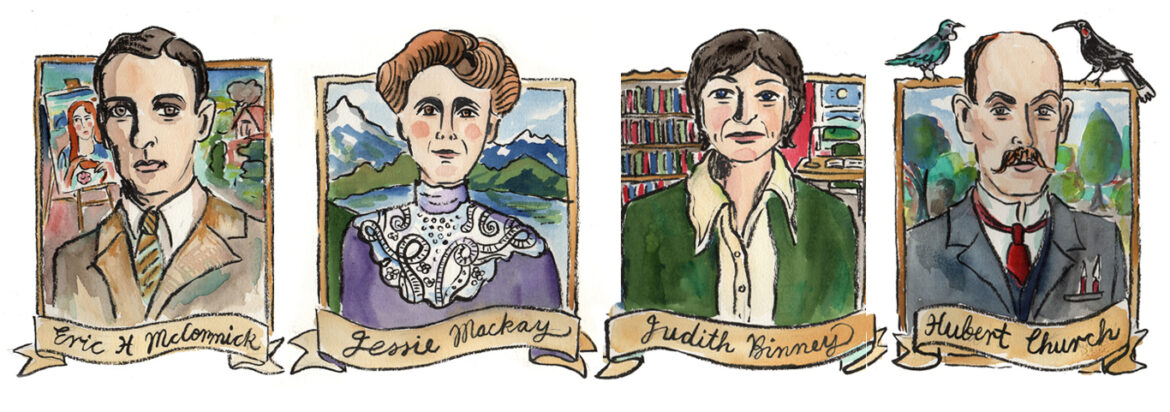

Yuten at Kiyomizudera in 2002, with three of the writers in the inaugural Kyoto Writers Residency: (left to right) Alfian Sa’at, Anna Cima and Hubert Antoine

Carl: I worked with a team of Japanese guys and one was a real loner, a bad boy, who raised hell, was always funny, individualistic and genuinely kind and really a free-thinker. I saw how his company treated him – the nail who stands up will be knocked down. He was sent out of his hometown, moved out to the sticks in Saitama. That really stung, watching the ‘wa’ assert itself over this unique individual. Literature to me is the assertion of individuality and it was a salutary lesson in the freedom I at least took for granted.

Paula: What are your literary influences, from Japan and elsewhere?

Carl: I read a lot of – and about – [Yukio] Mishima before I wrote The Method Actors, to try to better understand the postwar shift in psyche, Mishima being a very complex reaction to this. The tension between the martial spirit and failure, loss, and how a culture transforms to accommodate this. I also loved Murakami Ryu’s Almost Transparent Blue (1976), set among a group of teenagers on the fringes of a US army base: I loved the decadence and lostness set alongside complex political realities. I was interested in the space between decadence (mostly among gaijin in my book) and the past not being past in Japan.

Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking had been recently published [in 1997], about the Japanese atrocity in China in 1937 and I found in Yaskuni Shrine – the controversial shrine to the war dead, including WWII – a strange little hardback called A rebuttal to the rape of Nanking where convoluted historiography and tortured data (and English) were used to assert that these events hadn’t happened. I was also influenced by shoujo manga, primary coloured emotions, deeply romantic and personal forms meeting with grinding bloody histories. It was almost an assertion of the purpose and rationale of what I thought literature should be in the face of histories documenting the deaths of hundreds of thousands – something to do with minutely observed human moments otherwise lost in the numbers of casualties.

This was where I was at in Tokyo at the time – squaring this life of pleasure, decadence and (relative) riches with the epic scale of the loss and warfare just decades ago. Trying somehow to make the hundreds of volumes of the Tokyo War Trials transcripts sit alongside a nomihodai [all you can drink] menu in a karaoke booth in Shibuya after the trains shut down.

Yuten: As Carl said, I think literature is something that liberates the individual. I recovered from my loneliness in ‘wa’ by reading Hermann Hesse’s novels and poetry. I rediscovered my lost homeland in literature.

As for Japanese literature, I was strongly influenced by Akira Kurosawa’s movie Rashomon. I was fascinated by the structure of the film, the camera angles, the music, and the movements of the actors. I especially like the composition, which requires the audience to mentally reconstruct the content of the film after viewing it, like most good literary works.

The film is based on the 1922 short story ‘In a Grove’ [or ‘In a Bamboo Grove’] by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, whose work I research in an academic field, and of course I am greatly influenced by Akutagawa’s works. [Note: Akutagawa also published a story called ‘Rashomon’ when he was a student, but Kurosawa only used a few details from this in the film.]

My debut work, Village of Flamingos, is set in Belgium. One day, the protagonist’s wife suddenly transforms into a flamingo. The villagers try to hide the bizarre fact, but other people find out. It turns out that most of the women in the village have turned into flamingos. In my work, I depict the disturbance of the villagers. One of the works that inspired me to write this is Akutagawa’s ‘Horse Legs.’ Akutagawa’s story is about a man who dies suddenly; is found – in the afterlife – to have died by mistake; and is brought back to life. However, the legs of his corpse are rotten, so his body is revived with the legs of a horse. The man is shy about the horse’s legs, and doesn’t tell his wife or colleagues, but gradually the horse’s legs take over his body.

Kobo Abe’s 1962 novel The Woman in the Dunes [or Sand Woman] is also a work that I really like and was influenced by. In addition, I am fascinated by Yoko Ogawa’s narrative style, the sense of distance from the characters, and the allegorical nature of her works.

Kirsten: I’m currently exploring similar literary territory to your work, Yuten (and I enjoyed your piece in Granta too). I don’t know if you would – or would want to – call it magical realism, but I enjoy the possibilities that exist when elements of the fantastical become embedded in what is otherwise an everyday world. I’m in the midst of writing my first novel and I’m finding magical realism to be a really useful genre in which to imagine alternative realities, particularly when it comes to trying to break open traditional relationships and responses to trauma.

Colleen: My story ‘Directions’, featuring multiple crow narrators, was directly influenced by the ghost voices in the novel Lincoln in the Bardo (2017) by George Saunders. I attended a masterclass of his, and have seen him speak twice. He’s an incredible teacher and writer, and I wish I’d read his analysis of Russian short stories, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain (2021), before completing my collection. I find his takes on the practice of writing comforting and inspiring, and enjoy his Story Club on Substack. He’s a practising Buddhist, which informs his writing. I have an enduring, deep interest in Buddhist philosophy sparked during my time in Japan, and these teachings helped me survive the loss of my daughter there.

I have every book by W. Somerset Maugham. He grew up in France but moved to England as a child after his parents died. He was never accepted by the world of letters despite being one of the most successful writers of his time. I like his clear, plainly written storytelling. ‘Rain’ is a brilliant short story set in Samoa [which Maugham visited in 1916]. He wrote many short stories set in Asia, and was a wanderer, like me.

I also love The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagan, in particular her lists: Elegants Things, Hateful Things, Things that Make One’s Heart Beat Faster. I listen to the New Yorker Fiction Podcast, where authors select and read a short story from the magazine archives and analyse it afterwards. ‘Barn Burning’ [from The Elephant Vanishes] by Haruki Murakami and ‘The Swimmer’ by John Cheever are faves. I love writing in the second person, so Bright Lights, Big City (1984) by Jay McInerney made an impact on me – I was impressed the author could maintain that voice so well over a whole novel.

I just registered that you went to Japan in ‘99 too, Carl! We might have crossed paths without even realising. It was such an interesting time to be in Tokyo.

Carl: Colleen! That’s crazy. There’s really such a small amount of foreigners in Tokyo at any one time. We may have even met eyes in Shinjuku – that assessing glance foreigners give each other. I’m psyched to read Kōhine now I’ve discovered you. I loved your self-portrait in Reading Room: ‘Who are you angry at?’ Many of us might benefit from being asked that as a young person.

Paula: ‘Barn Burning’ was a re-working of the William Faulkner story of the same name, published in 1939. Both were source material for the fantastic 2018 Korean film Burning, directed by Lee Chang-dong, who also directed Peppermint Candy (2000). Sorry: I have to insert something about Korea into every conversation.

And my final question: if you could transport yourselves right now to a particular place in Japan, where would it be? What would you be doing there? Yuten, this question is for you as well.

Carl: If I were back in TKO I would probably be eating, and probably at my favourite kaiten zushi in Ikebukuro, ordering o-toro, the fattiest of tuna cuts, made for me by hand by the stern old sushi chefs. But afterwards, I’d like to cross this bridge over the Shakujii river in heavy rain in blossom season as I did once when the river rose to fill this canyon up to the road, an endless violent cataract of seething brown blanketed in twitching white petals.

Hanami, or blossom viewing, is about as sad a Japanese cliche as there is but this was a profound moment in a profound place at a profound time for me. There are hundreds more places I’d go again: Nara; the high rail bridge over the river at Akabane at night and the endless ocean of peopled night; the viewing platform over the floating forest of Aokigahara; Nagasaki; Shimabara and the tokens I found there still placed today by the hidden Christians to commemorate a 17th-century massacre of 16,000 – places that gave me migraines and brought me to tears for their beauty.

Colleen: It’s too hard to choose one place. Like Carl, one of the first things I would do is eat ōtoro – it melts in your mouth and is my absolute all-time favourite kai. Tino reka! My favourite sushi place is in Nakameguro by the Meguro River (more of a canal really), and the chefs are notoriously surly. I went there so often they grudgingly accepted me and would serve up my regular order of amaebi (sweet shrimp) without me asking for it. Nakameguro is also a beautiful spot for Hanami.

I would also go to Ukai Toriyama. It’s nestled in dense forest near Mount Takao and you dine in teahouse-style private tatami rooms surrounded by koi ponds and gardens where they grow a lot of their own produce, and make their own wasabi. The food is exquisite and the atmosphere is sublime.

Finally, I would go to Shunkoin Temple in Kyoto for a Zen meditation retreat. I stayed here before leaving Japan. The temple is within a large complex of 50 temples, Myōshinji. Some of the temples are over 400 years old. The two oldest ones emanate a powerful mauri that is difficult to describe. They are so imposing; it’s a little spooky. I recall asking a taxi driver to take me there, but he insisted it would be closed to the public as it was after five. He was astounded that I was actually staying there. The priest at Shunkoin had opened his small temple for guests, in an effort to raise funds. When I arrived, I couldn’t believe I was staying there too. That’s one of my best memories: entering the gates of Myōshinji at dusk, a chill down my spine as I passed by the Butsuden Hall, alone in Kyoto.

Kirsten: I am torn between wanting to be around the energy and vitality of Tokyo and the peaceful vibe of cycle touring through Hokkaido.

If I was in Tokyo, I’d want to go back to Shibuya and ride my bike through the little side streets and busy thoroughfares on the way to an izakaya, noodle house, coffee bar or stationery store.

I would also love to circumnavigate Hokkaido again by bike, but if I had to choose one area specifically, I would choose the coast near Wakkanai. The slow, de-habited feel of the many fishing villages, with their shrines, knots of fishing nets and elderly inhabitants, really reminded me of my childhood, visiting many of the Scottish Isles. As someone who is not particularly ‘practical’ in what they do for a living, I am always in awe of anyone who literally sustains themselves, their whānau and community.

Yuten: Wow, what a fun question! If I can go anywhere, not just in Japan, I will answer next to a sea turtle swimming in the sea. For me, sea turtles are sacred creatures. It moves very fast when it enters the sea, even though it moves very slowly on land. Its shape is completely different from that of a fish and I think the sea turtle is a symbol of diversity in the sea. The sea turtle swimming gracefully, seen in Hawaii, taught me the beauty of living. So I always want to jump in next to the sea turtle. (I like land tortoises too.)

When asked where I want to go in Japan now, I want to go to the Iruka Kissa-Bar in Kyoto. It was a spacious coffee shop and bar with very good music. There were only four tables near the handmade windows. The food was also good. The katsu-don and tomato sandwich were exquisite (and cheap) and could not be eaten elsewhere. The original cocktails included ‘Frozen Best Score (165000)’ – yes, the owner was a fan of Haruki Murakami. If you asked for a cocktail, the manager would change the music – for example, if you asked for the ‘Norwegian Wood,’ they’d play ‘Norwegian Wood’. It was just a few minutes from my house, and it was my favourite relaxing spot. Unfortunately, it suddenly closed at the end of last year. That’s why I want to go there now.

If I choose a place I can really go, I want to go to Beppu in Kyushu. Beppu is famous for its many hot springs. There are 27,000 sources of hot springs in Japan, of which 2,200 are in Beppu. I lived in Beppu for three and a half years, and I went to a hot spring almost every day. It’s a pity that the hot springs in Beppu are really very-very hot, so I can’t be in there for more than three minutes. There are so many sources of hot springs: in Beppu water from the hot springs flows in the groove of the road, and steam rises everywhere in the city. (If you search ‘Beppu’, you will see images of steam as if it were receiving a bombing.) It was a very fun wonderland with a lot of energy.

I heard that the New Zealand that I will visit soon is a wonderful land too. While reading Taste of Clouds, I saw many of the sentences focusing on and describing nature in order to understand Japan. I am very interested in the land of New Zealand, which has nurtured such writers’ eyes.

Taste of Clouds: New Zealand Writers Encounter Japan is a free e-sampler created by the Academy of NZ Literature. The design and translation team were Takako and Milton Bell. Please download and share.

Print copies are available in Japan from the Kyoto Writers Residency.

‘Inspiration is the name for a privileged kind of listening’ - David Howard

.

. .

. .

.

..

.. ..

..