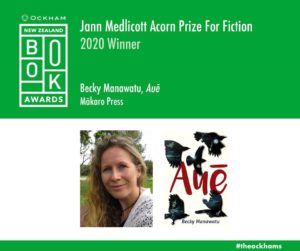

Fiction Writers’ Round Table 2021

This year’s finalists for the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction are novelist Pip Adam (Nothing to See); short story writer Airini Beautrais (Bug Week): Catherine Chidgey (Remote Sympathy); and Brannavan Gnanalingam (Sprigs). The writers talked via Google doc in April 2021, with questions from Paula Morris.

Paula: Congratulations on your shortlisting for the big prize in fiction. How is this particular book different for you? What are you doing (or trying to do) in this book that moves you somewhere new as a writer?

Catherine: For me, the book marks a return to the same historical period I explored in The Wish Child. Yet it also feels like new and challenging territory. In that earlier novel, the story unfolded in domestic settings and the camps existed only as shadows in the margins. In Remote Sympathy, I step inside the fence, as it were, with Buchenwald forming the backdrop. It felt like a step onto hallowed ground, and I was aware of a real responsibility to represent that particular place and history as accurately as possible

Brannavan: This book is much bigger than anything I’ve written, both in terms of physical size and scope. That took a lot more effort emotionally and intellectually, and hopefully I do the subject matter justice. It was terrifying to write—I’m nervous most of the time when I write—but I knew I could easily get things wrong or contribute nothing to the discourse. So I found myself thinking harder and being more ruthless in the edit than I’ve ever been before.

Pip: Nothing to See is a book that feels to me like it sustains an idea in a bigger time and space frame than my other books. I still feel like I can’t actually write a novel but I’m quite obsessed with the form. I love the puzzle quality of it. I have friends that do Sudoku and crosswords and I think I get the same stimulation out of writing novels. I think I’m a lot more vulnerable in this than my previous writing.

I was raised by ‘tough books’, often written by authors who turned out to be terrible people, and I’ve become really interested in what this meant to the way my imagination was formed. I feel like this book was the beginning of me ‘re-parenting’ my imagination into ways of writing that are willing to approach certain topics, tough topics, in ways that are perhaps less damaging, that show more of my experience and try not to fall into narratives from the mainstream that re-traumatise. Brannavan and I have talked a bit about this. I have been really interested in how you’ve talked about this in relation to Sprigs.

Airini: This book is a different genre for me, as I’ve previously published poetry books. I’ve always tinkered with short fiction, but it took me until 2018 to finish the collection that is now Bug Week. What I was trying to do was figure out how to successfully write a short story. I was also very interested in exploring female experiences from a variety of angles.

.

Paula: Is every book a way of figuring out how to successfully write it, even for those of you who have published fiction before?

Catherine: Every time I start a new book, I can’t remember how to do it. A strange amnesia sets in. I think the euphoria of finishing a novel, for me, obliterates the memory of the sheer difficulty of the task, along with the memory of how I came up with solutions to seemingly insurmountable problems.

Often I’ve found myself asking my husband: Did I face these same dead ends with the last one? (Yes, dear.) What did I do then? (Swore a lot and stuck some more Post-Its on the wall.) But every book is different and is trying to tell a story in a different way. Every book requires its own particular manual, even if that’s just an idea of the finished text that you keep in your head throughout the writing process.

Pip: So agree, Catherine!! Last year, someone showed me ‘Of Modern Poetry’ by Wallace Stevens. It has this line in it:

It has

To construct a new stage. It has to be on that stage

.

And I was like, ‘That’s it!’ Like every new idea or scenario or group of people seems to demand something new from the form. I’m in awe of the way Airini does it in Bug Week. It’s like when you do yoga and you inhale then exhale into a new position. Each story demands a new pressure on the language.

I think this reimagining of the form is what I love about the novel. I get excited when I see other people do it. It’s in all these books but also in the high-wire machinery Catherine set in motion in The Beat of the Pendulum. And the way Brannavan sort of winds up the second-person narrative so tight and then lets it go in You Should Have Come Here When You Were Not Here. People often try to proclaim the novel dead but it’s like some amazing Frankenstein’s monster, loved and sewn back into being out of necessity because each new story demands new science.

Catherine: Ah, I love that Wallace Stevens quote, Pip. Must remember it. And thank you for name-checking Pendulum! That felt very risky, form-wise, and in lots of other ways. I love books that push against what fiction is supposed to do and at the same time I’m aware of not wanting to indulge in gimmickry for gimmickry’s sake … ugh, but we can tie ourselves up in knots! In the end you just have to write the thing that is demanding to be written and hope that some other people might enjoy it too.

Brannavan: I agree with all of this! It has to start afresh each time, as well, which is irritating because you think you’ve got it sorted by the time you’ve hit your umpteenth edit of your previous book. For me, form always follows content and I always structure my books around a question I’m trying to answer. It means, for me, the structure of the book lends itself towards answering that question—I know, I know, I’m trained as a lawyer and with the whole idea of a theory of the case structuring an entire period of work.

The thing I find fascinating is how weird all of our books are formally, yet people seem to have responded to them despite (or because) of that—none of them follow any sort of traditional novel structure. And they’re all so different from your previous work, which seems to confirm Paula’s question. But your books don’t feel self-conscious in terms of structure either, in that there’s a really strong sense of narrative and character.

Catherine: Yes, a question you’re trying to answer, Brannavan—that’s a wonderful description. What is your central question in Sprigs?

Brannavan: My question was: how does the system bury a victim’s / survivor’s voice (and how can they find it, nevertheless)? And from there, it was trying to figure out what the ‘system’ is.

Catherine: So important to start with something specific like that and allow it to inform the ‘bigger’ questions/themes.

Pip: I love this idea so much. I love thinking about that question in regards to Sprigs. And it reminded of, erm, another quote. Bahaha. I have *no* original ideas. China Miéville (via Jordy Rosenberg): ‘Fiction is not so dissimilar to scholarly writing. Both have arguments. But fiction writing isn’t driven by the necessity that the argument of the work be right.’

I love this idea of argument/question being a way into and around a story. And YES! I love what you say, Catherine, about the story that is demanding to be told. I like the way all these ideas kind of subvert the idea of the lone artist in a garret and point toward something about communities and conversations and maybe the way things come to us/me when we’re/I’m *in* the world. I’ve always been interested in that word ‘Zeitgeist’. I don’t think I totally understand what it means but I sort of mis/understand it as a bigger conversation or consciousness.

Catherine: I would translate it as ‘the spirit of the times’—i.e. the spirit of a particular era. And there’s also that weird and maddening phenomenon of what feels like a totally original idea coming to you, and then you hear that same week that another book is about to be released that is very similar. Or a movie. Or a Netflix series.

.

Paula: I was interviewed recently about the fiction shortlist and asked what it ‘says’ about NZ literature right now. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Brannavan: I’m wary of making grand statements about what the four books might be saying about New Zealand literature, because that runs the risk of excluding books that are doing completely different things but are also firmly ‘New Zealand literature’. It creates the risk of assuming geographical location creates some sort of unified approach or model. I think our four books are quite different, even if they’re all quite political. I found your three books all so assured and confident—if anything, that could be something I see as a commonality across your works and could be expressing something about the state of New Zealand literature, but maybe that confidence isn’t new or unusual, I don’t know.

That said, I know Sprigs was heavily influenced by a bunch of New Zealand writing, such as Pip’s The New Animals, Carl Shuker‘s The Lazy Boys, Tina Makereti’s The Imaginary Lives of James Pōneke, for example. I think there are also some thematic similarities (e.g. damaged people dealing with trauma) in mine to other recent books like Nothing to See or David Coventry’s Dance Prone, even though we all wrote our books independently. Ultimately, I’d like to think my book is part of wider conversations we’re having within our various literatures and have been having for a while.

Catherine: Perhaps it’s folly to draw conclusions from a sample of four. I will say that when I think of the fiction published here in the last year, though, I’m excited at the range of our voices—the creative risks we are taking, the difficult, funny, provocative stories we are telling. I see that in my students, too—the desire to take their writing to sometimes uncomfortable places in order to produce work that matters.

Pip: I agree with what Brannavan and Catherine said. I feel like NZ literature is such a vast and varied thing. And I want to echo Catherine’s thoughts about how excited I feel at the moment about all the writing that is happening in so many different ways and forms. I feel really excited about the spaces people are making and the connections we are building between and through those spaces.

I know there are still folk and stories missing. I think it’s always important to ask of any room I’m in ‘who’s not here?’ It makes me sad and angry and want to try harder when I think about this, and I do have hope that through work to create and strengthen our communities we’re also building the skills to support and make space for new voices and forms.

Airini: I think it’s important to remember this is an award judged by a panel of humans and there are going to be processes to follow. There’s no such thing as an objectively judged award. It’s a little like how every year poets get excited or upset about Best New Zealand Poems. Someone got asked to pick 25 personal favourites and they did. There will always be lots missing.

I think choosing the award judges is important and working on a panel by consensus is important. In a small country it’s easy to feel a sense of responsibility or owing people favours—or the opposite. People do hold grudges. The NZ Book Awards doesn’t look like the way it did in the 1980s but does it look like an accurate representation of who is writing in New Zealand? No, but we do need to keep talking about why/why not.

This morning I was in Whitcoulls with my kids and I saw the NZ top 50 books (by Whitcoulls sales) on the shelf. It’s not an accurate representation of what people are reading but it does show some trends. I was happy to see Elizabeth Knox in there.

.

Paula: So, who is not here—not just on the Ockhams shortlist or longlist, but in general? This is a discussion I’m involved in all the time.

Airini: I want to go right back to how books get written in the first place. I think we need to ask ourselves how inequalities in literacy arise and are perpetuated. To write books you need to write well. You also need to read well. I have worked in education for 15 years in a bunch of different fields and met a lot of people who struggle with writing especially. Many of these people were intelligent, interesting people with a lot of stories to tell.

If we live in a country where functional literacy, i.e. the ability to read and write beyond what’s required for everyday life, is low, that is going to affect both the amount and the diversity of local writing being written, published and read.

Our ‘literary’ culture in NZ still has very strong roots in the Western canon, but that’s not the only form of storytelling or communicating. It’s a little like how contemporary classical music has European ancestry, but there’s all these other musical genres that get dismissed as ‘popular’ or ‘world’, i.e. not intellectual.

So I think we need to address massive socioeconomic and political inequalities on a societal level, and work on decolonisation, before we can get better diversity in the book world, but we also need to ask ‘what are books?’ And ‘why are books?’

Catherine: I completely agree with you, Airini, that we need to drill down into inequalities in education. Who is the system still failing, and why? I see those inequalities expressed in my students—and they are the ones fortunate enough to have made it to tertiary level. In terms of who is not here, in a wider sense—it does feel that things are changing, but a lot of voices remain under-represented. Writers of colour, queer writers, disabled writers, refugee writers.

I have to say, in New Zealand I’ve never really felt marginalised as a woman writer—and now, I suppose, a mature woman writer (yikes). However, I definitely see that process in play overseas. It’s all about debuts in the UK and US publishing scenes: youth is the trump card, but particularly so if you’re a woman. A ‘mature’ writer friend of mine, who’s trying to get her absolutely brilliant novel published offshore, has been told as much: it’s not her writing that’s unmarketable, it’s her age. I haven’t heard of a single equivalent story from male writers.

The diversity of my students’ work gives me enormous hope for our up-and-coming voices, though (and up-and-coming includes voices of mature writers): one student has produced a queer Māori sci-fi novel and a queer Māori adaptation of Hamlet; another a joyous, funny, provocative coming-out memoir; another an Indian YA fantasy novel; another a futuristic fantasy with a queer disabled narrator.

Airini: It’s interesting that you mention age, Catherine. While acknowledging the privileges I do have, my personal experience as a writer has been very tied up with being a woman. It seemed like a non-issue until I had children and also until I was over 30. There was a really weird sense of having lost some kind of cultural capital and that this was somehow tied to my ovarian supply. Perhaps I had the misfortune to know some older male writers with a blatant fetish for hot young women. The stalkers of Instagram and Twitter.

At that point you think, well, it’s not about the writing! I also had an experience at a festival where I was talking to one of my heroes and she mentioned some younger writers had just scoffed at her and walked away. She said, ‘I just feel so over.’ So if our success is tied up with our marketability, and that’s tied up with youth and physical appearance, what the fuck. It’s something I rage about a lot.

I agree with what you’ve said above about marginalised groups, but I do think gender equality—for all genders—has a long way to go. On a related note, while working towards diversity, we need to stop ‘othering’ writers of different cultures, genders and sexualities, and expecting them to write into a stereotype. Michalia Arathimos has written a lot about this.

Brannavan: I certainly agree with Airini that these are structural issues and reflect wider socio-economic factors. I do think though that literature is well behind other artforms in terms of prioritising other voices. Its various gatekeepers (publishers, universities, agents, funding bodies, review sections, awards) are much more conservative than other artform gatekeepers. It’s perhaps because my background was in film and popular music that I see literature as well behind the times. Of course, film and music have their own issues and many of the issues raised above, but the conversations are much louder there. I’d like to think it’s changing (especially as there are so many diverse voices on the margins) but institutionally and structurally, I don’t think it’s changed all that much from Janis Freegard’s analysis a few years back that showed published New Zealand literature does not come remotely close to representing New Zealand demographically.

I think there’s also a question of what form of books get excluded too, as Pip and Airini have mentioned earlier. I unashamedly write political fiction on serious topics because that’s what I do and it’s what I’ve always done. It wasn’t deliberate, but I’ve also come to realise that that’s the writing that tends to get reviewed or funded and, it must be said, considered for awards. Writers who work in genre (whatever that actually means) or in other forms tend to be marginalised in those conversations.

I’ve never considered myself closed off to other forms of writing especially given my own reading habits, but I also wonder if I need to be doing more to promote other writers, or use my voice to promote other types of writing, where possible i.e. the barriers become more real because writers like me who benefit from the current barriers aren’t actively trying to break them down.

Pip: I loved reading these answers. So much to think about and I agree with so much of it. I don’t have a lot more to add but I am interested in how culture shapes politics and is used by politics to justify and shore up certain ideals and policies. When I say ‘politics’ I mean it in a really broad sense, not just ‘government’ but in all sorts of places where we do things and where power hierarchies establish themselves and structures of capitalism take hold. I’m thinking especially around rape culture, but I think it’s true for white supremacy, the prison industrial complex, anti-queer hate, ableism.

I’m becoming very interested in para-social grooming. I used to think it felt a bit paranoid and conspiratorial to keep asking the ‘snake eating itself’ questions, ‘Who’s in the room? How are the stories we’re privileging affecting who’s in the room?’ But I think anyone who reads anything about, for instance, Dylan Farrow’s story, can see that if we don’t question the stories, we’re giving room to we set the odds against certain folk’s stories. This is why I feel hopeful, I think. I listened to an interview with Laurie Anderson last night and she was talking about the idea of how it’s impossible to be an individual, to stand out, in the current world. I felt really excited about this. It seemed like such an exciting dissolution of power and the ‘singular genius’.

When I watch how folk are curating their own cultural landscape these days I get very excited. Through different forms of publishing and broadcast, communities are able to talk in ways that are accessible to people inside and outside those communities. This multiplicity of experience seems to mean it’s very hard for certain experiences to be entrenched or pervasive. I feel very hopeful and love that these conversations are going on.

.

Paula: Brannavan, you’ve talked about the books you feel influenced Sprigs. In Salman Rushdie’s essay in the Guardian about Midnight’s Children at 40, he writes a great deal about the books and writers that influenced him writing this – and also how they helped answer some questions about structure, voice and point of view. All of you: are there any particular books that have shown you the way? (Or a way, at least.) If not for this book, for another?

Brannavan: The three books I mentioned earlier were hugely influential. I loved the way Pip’s narrative focus ‘floated’ from character to character in The New Animals, and I think Part 3 in particular was shaped by that approach (I also found Virginie Despentes’ Vernon Subutex and a lot of Svetlana Alexieviche as well extremely influential in that regard). With The Imaginary Lives of James Pōneke, I was heavily influenced by the way Tina shows how subjects are constituted and reconstituted (by trauma or otherwise). And I just love Carl’s writing—I think he’s one of the most interesting writers around, whether it’s thematically or formally.

Plus there are heaps of fearless writers from Aotearoa who you can’t help but be impressed by their forthrightness and refusal to pull any punches—I’m thinking the likes of essa may ranapiri, Hana Pera Aoake, Tusiata Avia, Chris Tse, Rose Lu, Anahera Gildea, Greg Kan. When you see writers as uncompromising as they are, it certainly helps with your own confidence. Plus my Lawrence & Gibson ‘stablemates’ Murdoch Stephens, Rhydian Thomas, Thomasin Sleigh and Sharon Lam are all so fantastic, and I’m so stoked to be working with them and learn from them.

The overall structure was heavily influenced by the way Balzac approaches his narrative. He spends more time on his ‘set-up’. He doesn’t dive straight into the action and takes his time to build the characters and setting. That means, when he lets the narrative go, you can get a lot of momentum by using emotional reactions and ‘inevitability’ to create pace. I’m a real sucker for French writing generally. Part 4 was heavily influenced by Maurice Blanchot’s ideas on the impossibility of words to capture experience. Georges Bataille was also important. Another reference point for Part 4 was M Nourbese Philip’s remarkable poetry book Zong! in which the way language collapses in response to horror.

Thematically, I was heavily influenced by Melissa Gira Grant’s and Sara Ahmed’s writing (particularly The Cultural Politics of Emotion). My background is theory and cultural studies though, as I did my MA in it—so that work (Foucault, Gramsci, Butler, Stuart Hall, Spivak, Bhabha etc.) underpins a lot of my writing and always has.

I genuinely could go on: I’ve barely scratched the surface of my influences for Sprigs. I haven’t even talked about film (my epigram is from Jean Renoir’s Rules of the Game) and music (Elvis Costello’s ‘This Year’s Girl’ was the song I listened to over and over again while writing this) and theatre (Victor Rodger and Ahi Karunaharan in particular) and TV, which have all been crucial to Sprigs as well.

Pip: I love the way questions like this build this web of ‘family’ connections. I find writing a book a really collaborative act in communion with other people’s work and thinking. I’m looking back at my notes for Nothing To See and I was very concerned with the ‘uncanny’—probably starting with Carmen Maria Machado’s response to a question about the ‘uncanny’ and the pull of it for women writers. She said, ‘I think there are probably lots of reasons [for this], but one of them is that being a woman is inherently uncanny. Your humanity is liminal; your body is forfeit; your mind is doubted as a matter of course. You exist in the periphery, and I think many women writers can’t help but respond to that state.’

I feel like this experience of ‘being inherently uncanny’ is not limited to women and the idea interested me—’an uncanny lived experience’, one that is determined by others and impossible to escape. This led me back to my Gothic favourites, Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre and also got me on a horror film bender. A moment of epiphany was the clam shell ‘from the future’ phones in It Follows. The device is completely out of context and time and is never explained, it acts as this interruption to time and place. I’m in love with the type of horror that is ‘just’ off. This ‘just’-offness is what drew me back and back and back to Bae Suah’s Nowhere to Be Found. It feels like realism, but is it?

A huge influence was Fleur Adcock’s poem ‘Gas’, which Helen Heath introduced me to when we recorded a podcast about her book Are Friends Electric ? Adcock’s poem is such an incredible work. I love it so much for its atmosphere and I think it says some interesting things about the passive experience. That was another thing I was interested in, ‘How can I write a ‘victim’ experience?’ I think Brannavan and I share this interest. I was reading every piece of fiction I could find about rape (I so wish Sprigs had been around) and there were certain ‘rhythms’ that kept coming up that I found really upsetting. I wonder if we also talk about death this way—a sort of necessary ‘getting over it’, a celebration of ‘resilience’ and this really disturbing idea that kept coming up, that violence is somehow ‘the making of us’, that something good comes out of it. One book I found at the time that really stands out as a counter to these kinds of stories is Elena Savage’s Yellow City.

In trying to get a handle on all this I was also grateful to a conversation between Jordy Rosenberg and China Miéville where they touch on the grotesque and sadism, and the sadism of capitalism. This was on the occasion of Miéville’s amazing novella The Census-Taker, which was also very helpful for my book. Miéville says this incredible thing in the conversation, ‘‘Just because the grotesque can be about sadism doesn’t mean it can’t be anti-sadistic. An anti-sadistic grotesque.’ Rosenberg’s own novel Confessions of the Fox was also a massive shining light for me, as was Andrea Lawlor’s Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl—both were very helpful models for dealing with interruptions to reality. I also fell in love with Kafka, especially ‘A Hunger Artist’ which I read over and over.

There were also, of course, countless writers closer to home. Jackson Nieuwland’s work showed me another kind of the uncanny that had the potential for humour. Rebecca Hawke’s work was, of course, incredibly helpful when I was looking at the grotesque and the uncanny. Also, conversations with Annaleese Jochems but also her magnificent book Baby. Cassandra Barnett’s MA manuscript showed me how big the novel could get. Sinead Overbye’s poetry and short stories helped me see new narrative structures and new ‘ways into’ a story. Anahera Gildea’s essay ‘Kōiwi Pāmamao—The Distance in our Bones’ blew my mind and made me question a lot of what I was doing. Then there is, of course, my good friend Laurence Fearnley, who read some early bits of the book and who was writing her book Scented at the same time, so these books are in conversation in that way.

Catherine: How fascinating to learn about these wide-ranging influences! That’s the glorious thing about reading—you never know when you’re going to stumble across something that feeds your work in ways that can feel absolutely vital and sometimes spookily pre-ordained.

I held Bernhard Schlink’s The Reader in my mind at times during the writing of Remote Sympathy, because of the fearless way that book engages with Germany’s difficult past. My book is very much concerned with the tendency to look the other way when confronted with uncomfortable truths, and although Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin is a very different work, the narrator’s husband turns an astonishingly blind eye to the malevolence developing in his own home, concerned as he is with building the perfect American family. I also believe Turtle’s grandfather and her teacher in Gabriel Tallent’s uncomfortably compelling My Absolute Darling can be read as partly complicit by their failure to take action to stop the abuse of the 14-year-old narrator.

It’s a long time since I read Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, but it has stayed with me, and I think Remote Sympathy strikes similar chords in its exploration of marital complexities and the nature of faith: what our beliefs can allow us to accept or reject.

Finally, Justice at Dachau by Joshua M. Greene gave me a chilling insight into the natures of many men like my SS officer character Dietrich. Greene tells the story of the chief prosecutor in the war-crimes trials that attempted to dispense justice to the perpetrators of Buchenwald and other camps. What struck me in reading this book, as well as in reading thousands of pages of trial transcripts, was just how ordinary these men sounded, and just how ordinary their home lives were—home lives peopled by spouses who must have had some knowledge of their actions. Those voices certainly shaped the voice of Dietrich.

Brannavan: I love hearing other people’s influences for a particular book and I agree, Pip, it really shows how collaborative writing actually is. One of the things I feel I don’t get to do enough is just talk about other artists’ work (I guess my background was reviewing). My response to the question was also influenced by Sara Ahmed’s idea that ‘citation is how we acknowledge our debt to those who came before; those who helped us find our way when the way was obscured.’ Ahmed notes that there’s a real political act in citation, particularly if in doing so, marginalised writers and thinkers get illuminated, but also more generally in the setting out ideas of solidarity and conversation that you both have mentioned.

Airini: I find it a bit hard to pinpoint anything that helped ‘show the way’ for Bug Week as a whole, as I wrote the stories over a decade or more. I think it was Katherine Mansfield that I first fell in love with as a young reader of short stories. Not just her writing but the whole bohemian mythology around her. I tend to go for the big female power hitters like Margaret Atwood, Jeanette Winterson, Alice Munro and Annie Proulx.

I really loved Frank Sargeson’s stories, although the New Zealand they describe is so different to the one we live in today. I’m a big fan of Ronald Hugh Morrieson and I think the dark comedy in my work is a bit of channelling of him. Patricia Grace, Witi Ihimaera, Tracey Slaughter, Emily Perkins, Lawrence Patchett and Tina Makereti are other local short fiction writers whose work I’ve admired. Pip’s collection Everything We Hoped For is freakin’ amazing, right from the opening lines.

I did a PhD on narrative in poetry and I think I learned a lot from that about structure and economy. Some all-time favourite poetic narratives are Anne Kennedy’s The Time of the Giants, Tusiata Avia’s Bloodclot, and Dorothy Porter’s The Monkey’s Mask (probably actually my favourite book ever).

.

Paula: Pip mentioned asking herself a question (‘How can I write a victim experience?’) that speaks to the essence of fiction writing: making the imaginative leap into lives and/or times that are not your own. What challenged you all most with these books? Does the imaginative leap thrill or scare you?

Pip: Just for transparency and clarity, the victim experience I was talking about was my own. That being said, this is not memoir. So even though the work starts with me trying to understand something about myself and my place in the world, to work out how to carry on—to answer the questions I have I very quickly have to move to imagination/fiction. That is how my brain works. ‘How do I care for myself, without the necessity to “get over” past pain?’ very quickly led to imagining a splitting of a person over two bodies.

I think the imaginative leap that I found most difficult was portraying a splitting rather than a doubling. I quickly decided against an imposter narrative. I didn’t want there to be the dynamic of an original and a usurper. It was one of the hardest things to try and express this shared history, shared being but separated bodies. It was challenging at a language level which is where I like my challenges—it feels like a puzzle that I am trying to figure out and I love that. I think I am at my happiest when I’m not sure I can do something. Like when I don’t have the skills to write what I’ve imagined. I remember Eleanor Catton saying once, she wasn’t sure she could pull off The Luminaries until she pushed send on the final version and that’s where I want to live.

Airini: It’s been interesting as a poet-turned-fiction-writer that the assumption of autobiography follows you. I’ve had people ask me if my stories are true and I just say ‘I’ve never been a man named Barry’ or something dumb like that. One or two of them do draw on direct experience (with some fictional details) and that has been pretty painful to write about. Now I want to write about it more but through a nonfiction lens: I want to write a collection of feminist essays where I just travel through the wreckage unravelling stuff and interrogating why things happen. I guess sometimes there’s adrenaline involved.

Apart from trauma-related personal stuff, the other thing I find hard is imposter syndrome. I have a science undergraduate degree and work as a science teacher, and I often feel like I’m not a ‘proper’ writer because I haven’t completely devoted my life to it. I’ve gone through phases of being immersed in the literary world and phases of being divorced from it. I’m at a low ebb currently with reading and writing. That part doesn’t thrill or scare me, it just makes me feel inadequate and embarrassed.

I broke some big creative writing workshop rule writing this collection. I have a talking bird and a conscious dead person. I’ll always find more personal value in writing that comes from a desire to experiment and create, than in writing that plays it safe. I trust my publisher not to publish something where an experiment went bad.

Brannavan: I totally get where you’re coming from, Airini, on the imposter syndrome side of things too. I’m not a formally trained writer, I didn’t do any creative writing courses at university (apart from a film scriptwriting course), and I kinda became a novelist by accident (a friend asked if I was going to write about a trip I was doing, and I said, sure, why not). I hate the idea that imposter syndrome is this thing where structural inequalities are foisted on individuals working within a particular system; that it’s left for the individuals to navigate themselves, rather than something to be fixed by those with the actual power.

I always write from a position of fear. All of my books have some deep part of me in them, but I use fiction to hide myself from it. That imaginative leap becomes a bit of a wardrobe for me to hide in. But the moment you start inhabiting other people’s worlds, that’s where, for me, I become utterly terrified I’m going to make a mistake. I don’t know who my audience is, but I know I have an audience and I have to keep in mind what I write has consequences (even if it’s just my Mum reading). I think writing from fear is a healthy position, because it means you’re more likely to take care in your writing. But fear can be a debilitating thing for a writer, so it’s a hard thing to manage. But ultimately, I want to create connections with my writing, or with other writers or narratives, or more generally create this sense of collaboration—that, for me, makes the imaginative leap also thrilling.

Airini: A lot of the writers I’ve talked to experience this fear and self-doubt. It can be completely paralysing. On the other hand, I feel it’s so important what you’ve said about writing having consequences. And I think those consequences are something I’ve seen change over the last couple of decades. It feels like we are finally able to say ‘I don’t want to read this *classic novel* because it’s racist/ misogynist etc’ instead of just being told to shut up and read the novel because it’s great. Our behaviour as people can affect the reception of our writing too. There are a growing number of publishers/ editors who are electing not to publish work by known rapists/abusers etc. I think that’s good.

On the other hand, I think there are some things we have less responsibility to as writers, or more freedom to play with. As a Pākehā writer I feel comfortable bending the truth with Pākehā history. For me, it’s strange seeing people get upset about something like The Crown not accurately portraying the monarchy. Sometimes it’s better to tell a good story than replicate fact. I think the Royal Family can cope.

Catherine: Oh, the imposter syndrome comments resonate for me too. Really, I think that state comes naturally to most writers. And to touch on what you said, Airini, I’m not sure that many of us, these days, CAN completely devote their lives to their writing—unless they strike it big and it starts to pay well!

The imaginative leap thrills me and scares me. Like you, Brannavan, I worry that I won’t get it right. But that doesn’t stop me wanting to try once an idea has its hooks in me. With Remote Sympathy, I was trying to embody characters whose lives are nothing like my own. In that situation, I think it’s useful to include small aspects of your own lived experience in order to make them three-dimensional and ‘genuine’, somehow—the memory of a particular taste, a particular injury or garment.

And bring on the talking birds! My next novel is narrated entirely by a magpie. That felt very freeing.

.

Paula: Three of you here have novels on the shortlist; Airini has a collection of stories. It’s unusual for a story collection to make the finalists’ list and in some other fiction prizes (e.g. the Booker), story collections aren’t even eligible. Could we close our conversation by talking about short stories? Is there a (published) story that you wish you’d written? For me it’s ‘Am Strande von Tanger’ by James Salter, which I love and envy.

Catherine: I didn’t know that about the Booker. How very depressing. I am delighted to see short stories on the Ockham’s shortlist, and I fail to understand why this is so rare, especially in New Zealand. We have a long, proud tradition of the form; Katherine Mansfield remains one of our most famous exports, after all. That the short story is the novel’s poor cousin seems to be a self-fulfilling prophecy—I know that agents and publishers (especially overseas) pressure insanely talented short-story writers to make the move to long-form fiction, and often the most brilliant collections go unpublished. That being the case, if readers are not exposed to the work, how can they develop an abiding taste for it? It’s maddening beyond belief. I’m proud to have initiated the Sargeson Prize in 2019 as a way of celebrating and nourishing the form here in New Zealand.

Borges’ ‘The Gospel According to Mark’ stuns me every time I return to it. The mounting sense of unease, the sly socio-political commentary—and a blood-chilling ending. You can’t achieve that kind of intensity in a novel. Utterly brilliant.

Brannavan: I love having these sorts of conversations and finding out points of solidarity and mutual recognition. I agree that that’s frustrating about short stories, and how they’re marginalised as a form (thanks to all three of you for flying the short story flag). I don’t have the skill to write short stories, so I’m in awe of people who can.

My response will be relatively straight down the line. For me it’s Chekhov’s ‘Easter Eve’. I read it when I was about 25 and it has stuck with me ever since, one of those moments where you reconsider everything you think art should be doing. Chekhov was obviously a master at short stories, but I was in awe at the way he was both deeply political and extremely compassionate in this. It’s also just beautiful and heart-breaking. It’s one of the things I’ve been conscious of trying to be better at. It’s easy to be cruel when writing politically, but if you’re trying to build solidarity, then care and compassion have to be at the heart of things.

Airini: So hard to pick! One story I can read and reread is ‘Spaceships Have Landed’ by Alice Munro. It has parties in the 1950s. It has alien abduction. It’s structurally weird. I love her matter-of-fact style.

Studying narrative poetry was a big eye opener in terms of how we distinguish forms and genres. Poems can be in prose and novels can be poetic. A lot of poems are stories. A lot of fiction is nonfiction and vice versa. I think we have tight genre boundaries to make library and bookstore shelving, and award categories, manageable. But I like to think as writers we have the freedom to blur the distinctions and just make what we want to make. I loved your approach to fiction and non-fiction in False River, Paula.

Pip: I love short stories so much. I love the scope it gives for a different type of character arc and the room there seems to be for experimentation. I always think about those published lectures by Frank O’Connor, The Lonely Voice, and how it offers ideas about how the short story has a different narrative voice and shape to novels. I don’t know about wishing I had written it, because I feel like it could only have been written by the author but I absolutely love Eru Hart’s story ‘May Board’ which is in Stories on the Four Winds. I also really love Emma Hislop’s story ‘The Game’ which was published in NewsRoom. Emma is writing some amazing stories that investigate power and feel very important to the moment we’re in.

I love the work of Sinead Overbye as well. I am quite excited how a few writers—Sinead and Cassandra Barnett come to mind—are really pushing through all sorts of genre and language boundaries, so the short story is getting to spread out into work that looks like poetry or nonfiction. It’s a really exciting time, I think. I guess I am also quite in love with Kafka’s short stories. I am so late to this party it’s embarrassing, but I read ‘A Hunger Artist’ over and over and over because it is so strange and heart-breaking, and I am currently reading and re-reading his short story ‘The Burrow’ because of the way it deals with sound. Thanks again, everyone. I’m really honoured to be in your company.

The Ockham New Zealand Book Awards take place on Wednesday 12 May in the Aotea Centre, Auckland, as part of the Auckland Writers Festival.